Vision and Motivation

In 1960, the world of American women was limited in almost every respect, from family life to the workplace. A woman was expected to follow one path: to marry in her early 20s, start a family quickly, and devote her life to homemaking. As one woman at the time put it, “The female doesn’t really expect a lot from life. She’s here as someone’s keeper — her husband’s or her children’s.”[1] As such, wives bore a full load of housekeeping and childcare, spending an average of 55 hours a week on domestic chores.[2] They were legally subject to their husbands via “head and master laws,” and they had no legal right to any of their husbands’ earnings or property, aside from a limited right to “proper support”; husbands, however, would control their wives’ property and earnings.[3] If the marriage deteriorated, divorce was difficult to obtain, as “no-fault” divorce was not an option, forcing women to prove wrongdoing on the part of their husbands in order to get divorced.[4]

In 1960, the world of American women was limited in almost every respect, from family life to the workplace. A woman was expected to follow one path: to marry in her early 20s, start a family quickly, and devote her life to homemaking. As one woman at the time put it, “The female doesn’t really expect a lot from life. She’s here as someone’s keeper — her husband’s or her children’s.”[1] As such, wives bore a full load of housekeeping and childcare, spending an average of 55 hours a week on domestic chores.[2] They were legally subject to their husbands via “head and master laws,” and they had no legal right to any of their husbands’ earnings or property, aside from a limited right to “proper support”; husbands, however, would control their wives’ property and earnings.[3] If the marriage deteriorated, divorce was difficult to obtain, as “no-fault” divorce was not an option, forcing women to prove wrongdoing on the part of their husbands in order to get divorced.[4]

The 38 percent of American women who worked in 1960 were largely limited to jobs as a teacher, nurse, or secretary.[5] Women were generally unwelcome in professional programs; as one medical school dean declared, “Hell yes, we have a quota…We do keep women out, when we can. We don’t want them here — and they don’t want them elsewhere, either, whether or not they’ll admit it.”[6] As a result, in 1960, women accounted for six percent of American doctors, three percent of lawyers, and less than one percent of engineers.[7] Working women were routinely paid lower salaries than men and denied opportunities to advance, as employers assumed they would soon become pregnant and quit their jobs, and that, unlike men, they did not have families to support.

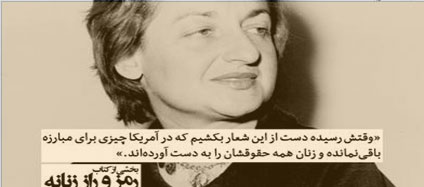

In 1962, Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique captured the frustration and even the despair of a generation of college-educated housewives who felt trapped and unfulfilled. As one said, “I’m desperate. I begin to feel I have no personality. I’m a server of food and a putter-on of pants and a bedmaker, somebody who can be called on when you want something. But who am I?”[8] Friedan stunned the nation by contradicting the accepted wisdom that housewives were content to serve their families and by calling on women to seek fulfillment in work outside the home. While Friedan’s writing largely spoke to an audience of educated, upper-middle-class white women, her work had such an impact that it is credited with sparking the “second wave” of the American feminist movement. Decades earlier, the “first wave” had pushed for women’s suffrage, culminating with the passage of the 19th Amendment that gave women the right to vote in 1920. Now a new generation would take up the call for equality beyond the law and into women’s lives.

Goals and Objectives

The feminist movement of the 1960s and ’70s originally focused on dismantling workplace inequality, such as a denial of access to better jobs and salary inequity, via anti-discrimination laws. In 1964, Representative Howard Smith of Virginia proposed to add a prohibition on gender discrimination into the Civil Rights Act that was under consideration. He was greeted by laughter from the other Congressmen, but with leadership from Representative Martha Griffiths of Michigan, the law passed with the amendment intact.[9]

The feminist movement of the 1960s and ’70s originally focused on dismantling workplace inequality, such as a denial of access to better jobs and salary inequity, via anti-discrimination laws. In 1964, Representative Howard Smith of Virginia proposed to add a prohibition on gender discrimination into the Civil Rights Act that was under consideration. He was greeted by laughter from the other Congressmen, but with leadership from Representative Martha Griffiths of Michigan, the law passed with the amendment intact.[9]

However, it quickly became clear that the newly established Equal Employment Opportunity Commission would not enforce the law’s protection of women workers, and so a group of feminists including Betty Friedan decided to found an organization that would fight gender discrimination through the courts and legislatures. In the summer of 1966, they launched the National Organization for Women (NOW), which went on to lobby Congress for pro-equality laws and assist women seeking legal aid as they battled workplace discrimination in the courts.[10]

As such, Betty Friedan’s generation sought not to dismantle the prevailing system but to open it up for women’s participation in a public, political level. However, the more radical “women’s liberation” movement was determined to completely overthrow the patriarchy that they believed was oppressing every facet of women’s lives, including their private lives.[11] They popularized the idea that “the personal is political” — that women’s political inequality had equally important personal ramifications, encompassing their relationships, sexuality, birth control and abortion, clothing and body image, and roles in marriage, housework and childcare.[12] As such, the different wings of the feminist movement sought women’s equality on both a political and personal level.

Leadership

The feminist movement was not rigidly structured or led by a single figure or group. As one feminist wrote, “The women’s movement is a non-hierarchical one. It does things collectively and experimentally.”[13] In fact, the movement was deeply divided between young and old, upper-class and lower-class, conservative and radical. Betty Friedan was determined to make the movement a respectable part of mainstream society and distanced herself from what she termed the “bra-burning, anti-man, politics-of-orgasm” school of feminism; she even spent years insinuating that the young feminist leader Gloria Steinem had sinister links to the FBI and CIA.[14] Younger feminists, for their part, distrusted the older generation and viewed NOW as stuffy and out of touch: “NOW’s demands and organizational style weren’t radical enough for us.”[15]

The feminist movement was not rigidly structured or led by a single figure or group. As one feminist wrote, “The women’s movement is a non-hierarchical one. It does things collectively and experimentally.”[13] In fact, the movement was deeply divided between young and old, upper-class and lower-class, conservative and radical. Betty Friedan was determined to make the movement a respectable part of mainstream society and distanced herself from what she termed the “bra-burning, anti-man, politics-of-orgasm” school of feminism; she even spent years insinuating that the young feminist leader Gloria Steinem had sinister links to the FBI and CIA.[14] Younger feminists, for their part, distrusted the older generation and viewed NOW as stuffy and out of touch: “NOW’s demands and organizational style weren’t radical enough for us.”[15]

When these divides were combined with a reluctance to choose official leaders for the movement, it gave the media an opening to anoint its own “feminist leaders,” leading to resentment within the movement. Meanwhile, in this leadership vacuum, the most assertive women promoted themselves as leaders, prompting attacks from other women who believed that all members of the movement should be equal in status.[16]

Nonetheless, women like Gloria Steinem and Germaine Greer attracted media attention through both their popular writings and their appealing image. They played a key role in representing feminism to the public and the media — providing attractive examples of women who were feminists without fitting the negative stereotypes of humorless, ugly, man-hating shrews.[17]

Civic Environment

In large part, the success of the feminist movement was driven by a favorable confluence of economic and societal changes. After World War II, the boom of the American economy outpaced the available workforce, making it necessary for women to fill new job openings; in fact, in the 1960s, two-thirds of all new jobs went to women.[18] As such, the nation simply had to accept the idea of women in the workforce. Meanwhile, as expectations for a comfortable middle-class lifestyle rose, having two incomes became critical to achieving this lifestyle, making women’s participation in the workforce still more acceptable.[19]

In large part, the success of the feminist movement was driven by a favorable confluence of economic and societal changes. After World War II, the boom of the American economy outpaced the available workforce, making it necessary for women to fill new job openings; in fact, in the 1960s, two-thirds of all new jobs went to women.[18] As such, the nation simply had to accept the idea of women in the workforce. Meanwhile, as expectations for a comfortable middle-class lifestyle rose, having two incomes became critical to achieving this lifestyle, making women’s participation in the workforce still more acceptable.[19]

But many of these women were relegated to low-paying clerical and administrative work. What opened the door for women to pursue professional careers was access to the Pill — reliable oral contraception. Knowing that they could now complete years of training or study and launch their career without being interrupted by pregnancy, a wave of young women began applying to medical, law, and business schools in the early 1970s. At the same time, the Pill made the “sexual revolution” possible, helping to break down the double standard that allowed premarital sex for men but prohibited it for women.

Feminist leaders were also inspired by the Civil Rights movement, through which many of them had gained civic organizing experience. At the same time, black women played a key role in the Civil Rights movement, especially through local organizations, but were shut out of leadership roles.[20] Meanwhile, the women’s anti-war movement was joined by a new generation of more radical young women protesting not only the Vietnam war but also “the way in which the traditional women’s peace movement condoned and even enforced the gender hierarchy in which men made war and women wept.”[21] On college campuses, women joined in the leftist student movement, but their efforts to incorporate women’s rights into the New Left were ignored or met with condescension from the male student leaders; at one New Politics conference, the chairman told a feminist activist, “Cool down, little girl. We have more important things to do here than talk about women’s problems.”[22] As a result, women split off from the movements that marginalized them in order to form their own movement.

At the same time, the FBI viewed the women’s movement as “part of the enemy, a challenge to American values,” as well as potentially violent and linked to other “extremist” movements.[23] It paid hundreds of female informants across the country to infiltrate the women’s movement.[24] While this infiltration intensified paranoia and eroded trust among activists, it did not change the course of the movement as it continued to fight for equal rights.[25]

Message and Audience

The women’s movement used different means to strive for equality: lobbying Congress to change laws; publicizing issues like rape and domestic violence through the media; and reaching out to ordinary women to both expand the movement and raise their awareness of how feminism could help them.

The women’s movement used different means to strive for equality: lobbying Congress to change laws; publicizing issues like rape and domestic violence through the media; and reaching out to ordinary women to both expand the movement and raise their awareness of how feminism could help them.

Early in the women’s liberation movement, which was deeply rooted in the New Left, activists took an aggressive approach to their protests. Protests against sexism in the media ranged from putting stickers saying “Sexist” on offensive advertisements to holding sit-ins at local media outlets, all the way to sabotage of newspaper offices.[26] This approach sometimes crossed the line into offensiveness, as at the 1968 demonstration outside the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, where activists protested objectification of women by waving derogatory signs like “Up Against the Wall, Miss America.” While the event attracted widespread media coverage (and launched the myth that feminists burned bras), the approach was alienating. As a result, many activists resolved to “stop using the ‘in-talk’ of the New Left/Hippie movement” and strive to reach ordinary women across the country.[27]

“Consciousness-raising groups” became an effective way to do so; in small groups in local communities, women explored topics such as family life, education, sex, and work from their personal perspectives. As they shared their stories, they began to understand themselves in relation to the patriarchal society they lived in, and they discovered their commonalities and built solidarity; as one said, “[I began to] see myself as part of a larger population of women. My circumstances are not unique, but…can be traced to the social structure.”[28]

Meanwhile, in their campaigns for the legalization of abortion, activists testified before state legislatures and held public “speak-outs” where women admitted to illegal abortions and explained their reasons for abortion; these events “brought abortion out of the closet where it had been hidden in secrecy and shame. It informed the public that most women were having abortions anyway. People spoke from their hearts. It was heart-rending.”[29] The “speak-out” was also used to publicize the largely unacknowledged phenomenon of rape, as activists also set up rape crisis centers and advocacy groups, and lobbied police departments and hospitals to treat rape victims with more sensitivity. [30] To publicize date rape, the annual “Take Back the Night” march on college campuses was launched in 1982.[31]

Activists also defined and campaigned against sexual harassment, which was legally defined as a violation of women’s rights in 1980; they also redefined spousal abuse as not a tradition but a crime, lobbied for legal change, and set up domestic violence shelters.[32] The women’s health movement set up a new goal of creating a women-centered health system, rather than the existing system that was often insensitive to women’s needs; activists educated themselves on the female body, began giving classes in homes, daycares, and churches, set up women’s clinics, and published the reference book Our Bodies, Ourselves.[33]

Meanwhile, the women’s movement was producing a huge number of journals in local communities across the country. While these journals were produced largely for members of the movement, Gloria Steinem’s Ms. Magazine, founded in 1971, expanded the audience to the general public at a national level. It publicized the problems ordinary women faced, published inspirational stories of successful women, and covered grassroots activist efforts across the country.[34]

At the same time, the movement used class action lawsuits, formal complaints, protests, and hearings to create legal change.[35] By the late 1970s, they had made tangible, far-reaching gains, including the outlawing of gender discrimination in education, college sports, and obtaining financial credit[36]; the banning of employment discrimination against pregnant women[37]; the legalization of abortion[38] and birth control[39]; and the establishment of “irreconcilable differences” as grounds for divorce and equalization of property division during divorce.[40] Members of the women’s movement were invigorated by these successes; as one said, “I knew I was a part of making history…It gave you a real high, because you knew real things could come out of it.”[41]

The August 1970 Women’s Strike for Equality, a nationwide wave of protests, marches, and sit-ins, captured this spirit of optimism. However, it soon gave way to a backlash exemplified by the failure of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), a proposed constitutional amendment that would protect women’s rights. It swiftly passed Congress in 1972 and was ratified by 30 states by the end of the following year. Still, it was unable to gain the 8 additional ratifications necessary by the 1982 deadline. At first there was widespread public support for the ERA by a margin of at least two to one — in theory, at least.[42] In practice, the public was still very conservative when it came to men’s and women’s roles, and a growing backlash against the changes feminism represented coincided with a backlash against gay rights and abortion rights, as led by the newly ascendant conservative movement, particularly the Christian right-wing.

The August 1970 Women’s Strike for Equality, a nationwide wave of protests, marches, and sit-ins, captured this spirit of optimism. However, it soon gave way to a backlash exemplified by the failure of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), a proposed constitutional amendment that would protect women’s rights. It swiftly passed Congress in 1972 and was ratified by 30 states by the end of the following year. Still, it was unable to gain the 8 additional ratifications necessary by the 1982 deadline. At first there was widespread public support for the ERA by a margin of at least two to one — in theory, at least.[42] In practice, the public was still very conservative when it came to men’s and women’s roles, and a growing backlash against the changes feminism represented coincided with a backlash against gay rights and abortion rights, as led by the newly ascendant conservative movement, particularly the Christian right-wing.

Moreover, the women’s movement failed to communicate the benefits of the ERA; by the time it passed Congress, many of the inequalities in the country’s laws had already been addressed, and it was hard for the public to see what positive impact the amendment could have.[43] The ERA’s opponents, on the other hand, painted a vivid picture of the terrible effects the ERA could have on the country. They attacked it as a plot to dismantle the foundations of American society, especially the family, and denounced the ERA’s “hidden agenda”: “taxpayer funding of abortions and the entire gay rights agenda.”[44] The ERA’s leading opponent, Phyllis Schlafly, denied that women were discriminated against at all; rather, she said, they enjoyed a sanctified position in American society through the “Christian tradition of chivalry,” which the ERA would destroy.[45] While the ERA failed, and the backlash against feminism has continued, the struggle for women’s rights has also continued, leaving a lasting impact on American society.

Outreach Activities

Due to the cross-cutting nature of the women’s movement, which included women who were already members of other movements, it was naturally suited to build links with these movements. For instance, some members of the feminist movement traveled abroad to meet Vietnamese women who were against the war in that country, in an effort to build sisterly anti-war solidarity.[46] Meanwhile, feminists with roots in the labor movement launched local groups to organize women workers, improve their working conditions, and fight for their equal rights on the job.[47] Black feminists targeted such issues as childcare, police repression, welfare, and healthcare, and founded the National Black Feminist Organization in 1973.[48]

By the end of the 1970s, activists burned out, and the women’s movement fragmented — but the services they founded, such as rape crisis centers, women’s shelters, and health clinics, were integrated into the mainstream as cities, universities, and religious organizations provided program funding.[49] Today the gains of the feminist movement — women’s equal access to education, their increased participation in politics and the workplace, their access to abortion and birth control, the existence of resources to aid domestic violence and rape victims, and the legal protection of women’s rights — are often taken for granted. While feminists continue to strive for increased equality, as Betty Friedan wrote, “What used to be the feminist agenda is now an everyday reality. The way women look at themselves, the way other people look at women, is completely different…then it was thirty years ago…Our daughters grow up with the same possibilities as our sons.”[50]

Learn More

News & Analysis

CWLU Herstory Project. “Classic Feminist Writings.” The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union.

“Living the Legacy: The Women’s Rights Movement, 1848-1998.” National Women’s History Project. 2002.

National Women’s History Project Resource Center. 2009.

Steinem, Gloria. “After Black Power, Women’s Liberation.” New York Magazine. 4 April 1969.

Books

Baxandall, Rosalyn and Linda Gordon, eds. Dear Sisters: Dispatches from the Women’s Liberation Movement. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

Brownmiller, Susan. In Our Time: Memoir of a Revolution. New York: Dial Press, 2000.

Collins, Gail. America’s Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. New York: Harper Collins, 2004.

Collins, Gail. When Everything Changed: The Amazing Journey of American Women from 1960 to the Present. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2009.

Coontz, Stephanie. A Strange Stirring: The Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s. New York: Basic Books, 2011.

Davis, Flora. Moving the Mountain: The Women’s Movement in America Since 1960. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991.

Faludi, Susan. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. New York: Anchor, 1991.

Freedman, Estelle. No Turning Back: The History of Feminism and the Future of Women. New York: Ballantine Books, 2003.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. New York: Norton & Company, 1963.

Helgesen, Sally. Everyday Revolutionaries: Working Women and the Transformation of American Life. New York: Doubleday, 1997.

Hooks, Bell. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. Cambridge: South End Press, 1984.

Jones, Jacqueline. Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Present. New York: Basic Books, 2009.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. Out to Work: The History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Rosen, Ruth. The World Split Open: How the Modern Women’s Movement Changed America. New York: Penguin, 2006.

Schneir, Miriam. Feminism in Our Time: The Essential Writings, World War II to the Present. New York: Vintage Books, 1994.

Siegel, Deborah. Sisterhood, Interrupted: From Radical Women to Girls Gone Wild. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Multimedia

Reichert, Julia and Jim Klein. Growing Up Female. 1971.

Footnotes

[1] Coontz, Stephanie. A Strange Stirring: The Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s. New York: Basic Books, 2011. 42.

[2] Coontz, Stephanie. “When We Hated Mom.” New York Times. 7 May. 2011.

[3] A Strange Stirring 46.

[4] Collins, Gail. When Everything Changed: The Amazing Journey of American Women from 1960 to the Present. New York: Little, Brown & Company, 2009. 43.

[5] “100 Years of Consumer Spending: 1960-61.” Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2006. PDF.

[6] Collins 38.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Collins 117.

[9] Ibid., 149-160.

[10] Ibid., 165-168.

[11] Ibid., 368-9.

[12] Rosen, Ruth. The World Split Open: How the Modern Women’s Movement Changed America. New York: Viking Penguin, 2000. 196.

[13] Collins 388.

[14] Sullivan, Patricia. “Voice of Feminism’s ‘Second Wave.'” Washington Post. 5 Feb. 2006.

[15] Rosen 84, 88.

[16] Ibid., 227-9.

[17] Ibid., 154, 217.

[18] Collins 194.

[19] Ibid., 199.

[20] Ibid., 238.

[21] Ibid., 367.

[22] Ibid., 372-3.

[23] Rosen 245-6.

[24] Ibid., 241.

[25] Ibid., 259-60.

[26] Ibid., 162.

[27] Ibid., 161.

[28] Ibid., 197, 248.

[29] Ibid., 158.

[30] Ibid., 182.

[31] Ibid., 184.

[32] Ibid., 186-7.

[33] Ibid., 176.

[34] Ibid., 211, 216.

[35] Ibid., 88-90.

[36] Title IX of the Education Amendments (1972); the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (1974).

[37] The Pregnancy Discrimination Act (1978).

[38] The Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision (1973).

[39] The Eisenstadt v. Baird Supreme Court ruling (1972).

[40] The Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act (1970), passed by the U.S. Uniform Law Commission, which strongly influenced state laws.

[41] Rosen 200.

[42] Daniels, Mark R., Robert Darcy, and Joseph W. Westphal. “The ERA Won — At Least in the Opinion Polls.” PS: Political Science and Politics 15:4 (Autumn 1982), American Political Science Association.

[43] Collins 444.

[44] Schlafly, Phyllis. “‘Equal rights’ for women: wrong then, wrong now.” Los Angeles Times, 8 April 2007.

[45] Collins 451.

[46] Rosen 137-8.

[47] Ibid., 268-9.

[48] Ibid., 282-4.

[49] Ibid., 270.

[50] Friedan, Betty. Life So Far: A Memoir. New York: Touchstone, 2000. 375.