Vision and motivation

Until December 6, 1865 upon the passing of the 13th amendment to the United States Constitution, it was legal for white Americans to own, sell, trade, and exploit slaves.

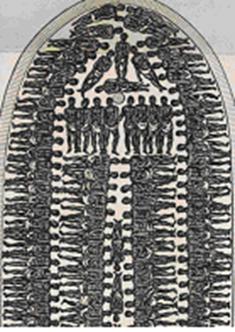

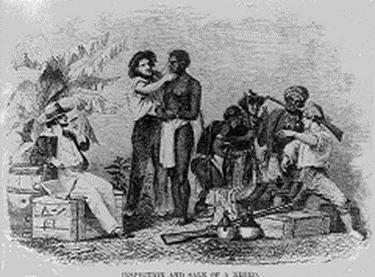

Slavery was ingrained in American history since before the country’s inception. Starting in the 16th century, massive cargo ships carrying kidnapped black Africans docked on American shores, where they would be auctioned off as slaves to the highest bidder. In 1789, Olaudah Equiano was one of the first slaves to write about his own experiences. Of his travel to America, he wrote:

“I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a salutation in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life: so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and on my refusing to eat, one of them held me fast by the hands and laid me across I think the windlass, and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. I had never seen among any people such instances of brutal cruelty.”[1]

Once in America, slaves attended to any and all tasks their masters ordered, including tending to agricultural fields, housework, performing as entertainment, and raising children. If they displeased their masters in any way, they could be denied food, water, or sleep, sold to a more violent family, forcibly separated from their family, or beaten.

William Green, a former slave wrote a book in 1853 after he was freed; his account was not atypical. In it, he writes,

“My father while he was a slave was belonged to a man by the name of Nace Rhodes. He was considered one of the meanest men any where about in those parts. He kept his servants always half starved and naked. He was never known to give his people enough to eat, and he worked them late and early. Daylight never found them in bed. Bed, indeed did I say, poor creatures they hardly knew what a bed was; all the bed they knew anything about was a bunch of straw on the cold damp earth.” [2]

By 1860, nearly four million slaves lived in the United States, accounting for nearly thirteen percent of the U.S. population and at least fifty percent of all slaves in the Western hemisphere.[3],[4]

Early abolitionists had been around since the institution of slavery, however, they were divided in what kind of future they envisioned for slavery. “Free Soil” advocates wanted to restrict the spread of slavery, contain it to the areas where it already exisited, and not eradicate it in its entirety. These “Free Soilers” would eventually organize into a political party in 1848 to bring their platform forward in a more organized fashion. However, by the late 1850s and the outbreak of the Civil War, the prevailing goal of the abolitionist movement was to eradicate the practice of slavery and free all slaves.

Civic environment

State experiments in banning slavery began in 1652 as Rhode Island banned the lifetime ownership of slaves, however there is little evidence this statute was ever enforced.[5] Vermont abolished slavery in 1777, while it was still an independent territory.[6] As it entered the United States as the 14th state, this law remained. Rhode Island and Connecticut, had both restricted the slave trade prior in 1774 by banning overseas slave importation, however slavery as a practice remained. While influenced by Quaker ideals, the restricting of slavery was not necessarily altrustic during this time period, but was used a political tactic to differentiate the states from others around them, asserting their independence in thought.[7],[8] As the abolition movement gained momentum, these religious ideals would grow to become a larger driving force.

In part due to a reaction against the growing industrialization of the United States, the Second Great Awakening beginning around 1790 with its height around the 1820s and 1830s consisting of a religious revivalism emphasizing humans’ ability to be spiritually saved through enacting good deeds and eradicating sins during life— a stark contrast to the previous notions of Calvinism that was built upon a life of deprivation and avoidance of sins. The Second Great Awakening ushered in an unprecedented era of performative worship across faith traditions. Northern abolitionists especially began to capitalize on this religious fervor to advocate against slavery on a moral basis. Other prominent social movements also found their roots in this newfound moralism, including the Women’s Suffrage and Temperance movements.[9]

By 1808, the federal Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves took effect, curtailing the importation of slaves via ship, while not addressing other aspects of slavery, and the political issue of slavery seemed to be solved for awhile.[10] This feeling would prove fleeting, as slavery became a central issue for American politics and served as a point of high contention with new states entering the Union. By 1819, the 22 states of the Union were evenly divided between slave states and free states. As Missouri petitioned for statehood, Congressman James Tallmadge Jr. of New York proposed amendments to the bill allowing it to enter only if it banned slavery in its constitution. As the North’s population was rapidly expanding due to industrialization, the Tallmadge Amendment easily passed in Congress, but failed to pass the evenly divided Senate. Its passage would have swayed the political bend of the U.S. Senate in favor of the free states, enraging many Southern states. The Tallmadge Amendment marked the first blatant politicization of slavery on a federal level. Despite abolitionism gaining a wider audience throughout the early 19th century, those who advocated for the continuation of slavery had significant political and economic power. John C. Calhoun, Vice President from 1825-1832, stated,

“But let me not be understood as admitting, even by implication, that the existing relations between the two races, in the slaveholding states, is an evil. Far otherwise; I hold it to be a good, as it has thus far proved itself to be, to both, and will continue to prove so, if not disturbed by the fell spirit of Abolition. I appeal to facts. Never before has the black race of Central Africa, from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically but morally and intellectually.”[11]

Anti-abolitionists fought to keep slavery for several political, social, and economic reasons. Southern states especially feared the negative effect that rapid abolition would have on the economy at both the state and federal levels, as much of their labor came from slaves. They believed that the cash crops upon which their economy was based, such as tobacco and cotton, would go unpicked and unsold, causing widespread economic collapse. As many of these crops were exported, they also believed global trade would be greatly affected. In response to the moralist arguments of abolitionists, they preached that slavery was preordained by God and found passages in the Bible to support their claims. All of these arguments were based upon racism and the belief that blacks were inferior and incapable of civility.

As these anti-abolitionists held great political power and wealth (that they gained from slavery), they were able to force compromises through on a federal level as free states wanted to avoid violent conflicts. In 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was federally passed as part of the Compromise of 1850. The Act specified that any runaway slave found in a free state must be returned to their owner and it explicitly denied runaway slaves the right to a trial by jury; this forced both Northern citizens and institutions to actively participate in slavery, something which until this point they had been able to have a largely apathetic view towards; “where before many in the North had little or no opinions or feelings on slavery, this law seemed to demand their direct assent to the practice of human bondage, and it galvanized Northern sentiments against slavery.”[12]

The idea of slavery as a political tool would continue to grow until reaching its breaking point on the border of Kansas and Missouri between 1854 and 1861, and it would eventually lead to the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861. Bloody Kansas, as the event is known as, forced slavery to the forefront of national politics in a way previously unseen. In 1820, the Missouri Compromise ushered in the practice of using a state’s latitude to determine whether or not it would be a free state or allow slavery; any state coming from within the Lousiana Purchase’s territory north of latitude 36°30′ was automatically free. However, the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act effectively overturned the 1820 Missouri Compromise and instituted a popular sovereignty principle instead, meaning residents of that state would decide if it were free or not. Activists on both sides of the issue flocked to these fledgling states to try and sway the outcome.[13] Unprecedented violence then occurred as the direct manifestation of pro- vs. anti-slavery ideologies. As the violence of Bloody Kansas continued to rage on the border states, the presidential election of 1860 loomed. Abraham Lincoln, a supporter of abolishing slavery, was elected President of the United States without even having been on the ballot in ten Southern states. Politicians in the South took this as a direct affront to their rights. Shortly after Lincoln’s 1861 inauguration, seven Southern states seceded from the Union in protest to form their own government. After the Civil War officially began with secessionist troops attacking in South Carolina, the states of Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina soon joined South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas to form the Confederate States of America. The Civil War continued into 1865.

Ultimately, after 750,000+ deaths, the Union won the Civil War, and the Confederacy was reabsorbed into the United States.[14] The North’s victory ensured that slavery would be abolished, and a series of amendments to the U.S. Constitution were passed to encode them into law. The 13th Amendment, ratified on December 6, 1865, formally abolished slavery, stating: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”[15] While the 13th Amendment eradicated the practice of slavery, it did not endow any rights onto those who became free upon its passage. The 14th Amendment, ratified on July 9, 1868, extended the definition of citizenship and states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”[16] Free blacks born in the United States were now considered citizens, however they still were unallowed to vote until the 15th Amendment, adopted in 1870, extended that right to African-American men.[17]

Leadership, audience, and outreach activities

The message of abolitionists shifted throughout the movement from limiting the spread of slavery to unequivocally eradicating the practice. As the movement grew in both scale and scope, the ways in which abolitionists advocated alternatives also shifted, from local social change to a large scale political movement.

Abolitionists were able to take advantage of the principles of the Second Great Awakening to craft a holistic moralist argument against the practice. Building upon the grassroots religious fervor that characterized the Second Great Awakening, abolitionists found themselves able to preach their message to a receptive audience on a scale unfathomable a few decades prior. Orators against slavery gained prominence and notoriety in the height of the Second Great Awakening and former slaves, such as Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass, were provided the opportunity to share their experiences with Northern audiences. Building upon the shifting attitudes about slavery, abolitionists began using media and cultural campaigns to further appeal to a mass audience and tug at their conscience. Abolitionists began touring as orators, speaking at churches and other public gatherings, as former slaves detailed their experiences for Northern audiences.

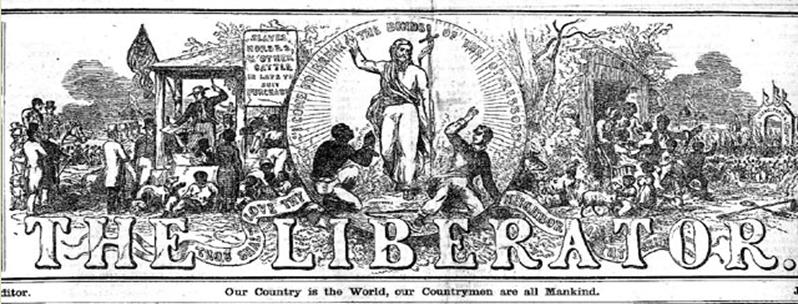

Artists and writers took up abolitionist themes in their work. Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a highly popular book that took up overt negative themes of the slave experience, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote a volume of poetry entitled Poems on Slavery, and various anti-slavery advocates created newspapers with country-wide circulations. William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp founded The Liberator in 1831, which appealed to moralism, and had a small, but important readership, including Douglass, who created his own publication The North Star in 1847.

In 1833, Garrison and Arthur Tappan founded the American Anti-Slavery Society, which became the leading activist arm of the movement, bringing together prominent abolitionists under the same umbrella, including: Douglass, William Wells Brown, Theodore Dwight Weld, James Birney, and notable suffragists Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott. The Society “denounced slavery as a sin that must be abolished immediately, endorsed nonviolence, and condemned racial prejudice.” By 1840, the American Anti-Slavery Society had more than 2,000 auxiliary societies throughout the U.S. and its membership grew to 150,000-200,000.[18] These societies “sponsored meetings, adopted resolutions, signed antislavery petitions to be sent to Congress, published journals and enlisted subscriptions, printed and distributed propaganda in vast quantities, and sent out agents and lecturers (70 in 1836 alone) to carry the antislavery message to Northern audiences.”[19] The Society’s activities were relatively well-received in Northern states and were responsible for bringing many new activists of all genders and races into the fold of the movement. However, the backlash that did come from pro-slavery activists was violent, as mailbags carrying propaganda were burned and mobs congregated outside of meeting places.[20] In 1837, prominent white abolitionist news editor and minister

Elijah Lovejoy was murdered by a pro-slavery mob that was threatening The Saint Louis Observer’s office, spurring some white Northern politicians to convert to the abolition movement and Northern citizens to vote in more anti-slavery politicians.[21]

The outbreak of Bloody Kansas forced politicians to engage with slavery as part of their platforms. Abraham Lincoln used the backdrop of Bloody Kansas to frame his objection to slavery. In his famous speech at Peoria, Illinois in 1854, which historians claim helped resurrect his political career on a federal level, he firmly opposed slavery in moralist terms, stating:

“This declared indifference, but as I must think, covert real zeal for the spread of slavery, I can not but hate. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world—enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites—causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty— criticizing the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.”[22]

In addition to the increasingly political nature of the movement, a more militant version of the abolition movement began post-Bloody Kansas. In 1859, after witnessing the violence of the Bloody Kansas border war for himself, abolitionist John Brown had the idea to lead a strike on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia and take over a military arsenal there. While his armed revolt ultimately failed and he was arrested, the event bestowed a great deal of notoriety upon Brown himself and the greater cause of abolitionism. He and his beliefs made newspapers all over the country, raising widespread awareness of the cause.

Legacy

The end of the Civil War and the passage of the 13th-15th Amendments did not usher in the end of racial discrimination in America. In fact, the direct effects of slavery on the United States continued more than 100 years post-abolition, and many effects can still be seen today. The legal abolition of slavery in the United States did not immediately mean equality or widespread civil rights for former slaves. Vast race-based economic, social, and political inequality remained rampant throughout the southern states for more than 100 years, as slavery reinvented itself as segregation. Despite African-American men winning the right to vote in 1870 under the 15th Amendment and women the right to vote in 1920 under the 19th Amendment, white politicians continued to construct structural impediments to utilizing these rights. They used discriminatory practices such as enacting poll taxes, administering literacy tests, and limiting transportation to polling stations that largely affected black voters. Not until the 1970s in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement did black citizens in many states have the same legal rights as their white counterparts, including attending the same public school systems, eating at the same restaurants, drinking from the same water fountains, and entering movie theatres through the same entrances.[23] Only with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a century after the abolition of slavery, did black Americans have their political agency formally protected under law. Despite the election of an African-American to the U.S. presidency in 2008, racially-based economic and social barriers to equality continue through to today. Nevertheless, America continues to correct itself.

Learn More

Books and Articles

- History.com editors. “Civil Rights Movement.” History. 27 October 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/abolitionist-movement

- “Abolition Movement.” National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/africanamericanheritage/abolitionmovement.htm

- “Abraham Lincoln: An Extraordinary Life.” National Museum of American History. https://americanhistory.si.edu/lincoln/president-lincoln

- “The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/african-american-odyssey/abolition.html

Accounts of Slavery

- Green, William, former slave. Narrative of events in the life of William Green, (formerly a slave.) Springfield [Mass.] L.M. Guernsey, Printer, 1853. https://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.06094/?sp=8

- “Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938.” Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/connections/narratives-slavery/file.html

- “Olaudah Equiano – life on board.” International Slavery Museum. http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ism/slavery/middle_passage/olaudah_equiano.aspx

Videos

- “Africans in America.” PBS. October 1998. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/home.html

- Burns, Ken. “The Civil War.” 1990. https://www.netflix.com/title/70202577

- “The Abolitionist Movement.” Robert H. Smith Center for the Constitution at James Madison’s Montpelier. 17 June 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w-9aSAwct34

Footnotes:

[1] “Olaudah Equiano – life on board,” International Slavery Museum, http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ism/slavery/middle_passage/olaudah_equiano.aspx.

[2] William Green. Narrative of events in the life of William Green, (formerly a slave.), Springfield: L.M. Guernsey, 1853, https://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.06094/?sp=8.

[3] Stanley L. Engerman, Richard Sutch, and Gavin Wright, “Slavery for Historical Statistics of the United States Millennial Edition,” University of California Project on the Historical Statistics of the United States, Center for Social and Economic Policy, 2003, https://economics.ucr.edu/papers/papers03/03-12.pdf.

[4] “Data Analysis: African Americans on the Eve of the Civil War,” Bowdoin College, https://www.bowdoin.edu/~prael/lesson/tables.htm.

[5] Olivia B. Waxman, “America’s First Anti-Slavery Statute Was Passed in 1652. Here’s Why It Was Ignored”, Time, 18 May 2017, ”https://time.com/4782885/rhode-island-antislavery/.

[6] “Vermont 1777: Early Steps Against Slavery,” National Museum of African American History & Culture, accessed June 2019, https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/vermont-1777-early-steps-against-slavery.

[7] “Vermont 1777: Early Steps Against Slavery,” https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/vermont-1777-early-steps-against-slavery.

[8] Olivia B. Waxman, “America’s First Anti-Slavery Statute Was Passed in 1652. Here’s Why It Was Ignored,” https://time.com/4782885/rhode-island-antislavery/.

[9] “The 1960s-70s American Feminist Movement: Breaking Down Barriers for Women,” Tavaana, E-Collaborative for Civic Education, accessed June 2019, https://tavaana.org/en/case-studies/1960s-70s-american-feminist-movement-breaking-down-barriers-women.

[10] “This Day in History March 02: Congress abolishes the African slave trade,” History, 9 February 2010, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/congress-abolishes-the-african-slave-trade.

[11] Gerald M. Capers, “John C. Calhoun,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed June 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-C-Calhoun.

[12] Winston Groom, Shiloh, 1862, Washington, DC: The National Geographic Society, 2012, https://books.google.com/books?.id=7_9IKUH3OXgC&pg=PA50&lpg=PA50&dq=%22Where+before+many+in+the+North+had+little+or+no+opinions+or+feelings+on+slavery,+this+law+seemed+to+demand+their+direct+assent+to+the+practice+of+human+bondage,+and+it+galvanized+Northern+sentiments+against+slavery.%22&source=bl&ots=sSBAhtlELe&sig=ACfU3U3EZn9FLyqaA1MCi9B8abDzDLEn3w&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi7u7nquqjjAhXKct8KHQ_gDCcQ6AEwAnoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22Where%20before%20many%20in%20the%20North%20had%20little%20or%20no%20opinions%20or%20feelings%20on%20slavery%2C%20this%20law%20seemed%20to%20demand%20their%20direct%20assent%20to%20the%20practice%20of%20human%20bondage%2C%20and%20it%20galvanized%20Northern%20sentiments%20.against%20slavery.%22&f=false.

[13] History.com editors, “Bleeding Kansas,” History, 27 October 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/19th-century/bleeding-kansas.

[14] Daniel Nasaw, “Who, What, Why: How many soldiers died in the US Civil War?” BBC, 4 April 2012, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-17604991.

[15] 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Abolition of Slavery, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/13th-amendment.

[16] “14th Amendment,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/amendmentxiv.

[17] History.com editors, “15th Amendment,” History, 9 November 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/fifteenth-amendment.

[18] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “American Anti-Slavery Society,” Encylopedia Britannica, accessed June 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/American-Anti-Slavery-Society

[19] “American Anti-Slavery Society,” Encylopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/American-Anti-Slavery-Society.

[20] History.com editors, “Abolitionist Movement,” History, 27 October 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/abolitionist-movement.

[21] “Today in History – November 7: Elijah Lovejoy,” Library of Congress, accessed June 2019, https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/november-07/.

[22] “Peoria Speech, October 16, 1854,” Lincoln Home, National Park Service, accessed June 2019, https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/peoriaspeech.htm.

[23] History.com editors, “Civil Rights Movement,” History, 27 October 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/civil-rights-movement.