Introduction

In 2016, air pollution masks began popping up on statues across the Chinese city of Chengdu.[1] As these statues stood in silent protest, a heavy smog coated their shoulders and faces. Citizens walked by peacefully, donning masks of their own, weary of the air pollution penetrating their lungs – a known cause of cardiovascular and heart diseases. By the end of 2016, more than 1 million Chinese deaths would be linked to air pollution.

The citizens of Chengdu were determined to protest this imminent threat, but their options were limited. Freedom of speech and assembly are severely curtailed in China.[2] Despite the subtle and peaceful nature of the statue protest, the regime cracked down. Riot police were quickly deployed and the city’s main square was closed.[3] Ideas of a mass protest were stifled, but a group of artists decided to keep fighting. The artists strapped on their masks and protested in a way they deemed legal: they simply walked around the city center. Eight of the artists were arrested.[4]

The masks soon came off the statues and protest fervor waned: the regime had won this battle. However, questions are left unanswered. In 2014, the Chinese regime declared war on air pollution and has worked with climate activists to this end. So, why did the regime crack down on this peaceful protest in Chengdu?

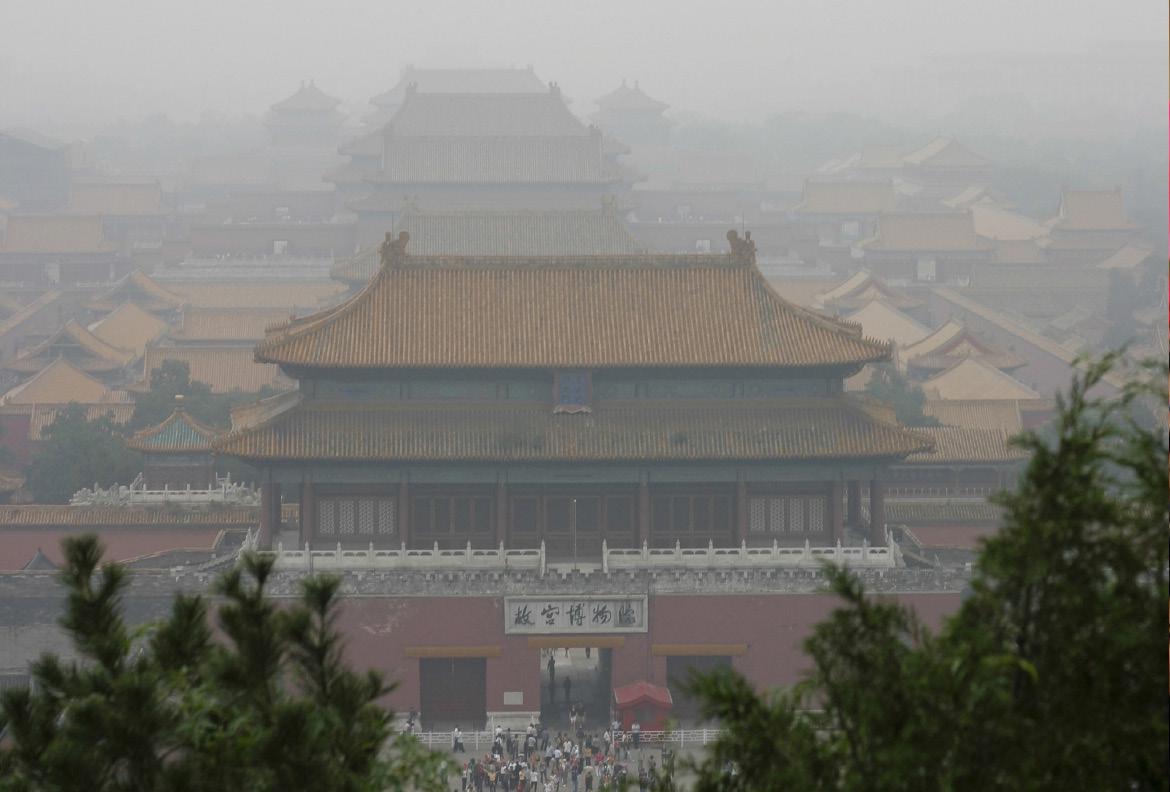

Smog over Beijing’s Forbidden City © Creative Commons, 2015 – Brian Jeffery Beggerly

Background

President Xi Jinping has intensified authoritarianism in China. Xi has eliminated term limits on the presidency, heightened surveillance and online censorship, increased persecution of ethnic minorities and oppresses civil society.[5] Freedom House (2019) classifies China as “not free.” China ranks 1/4 for individual freedom to express “personal views on political or other sensitive topics,” 1/4 for freedom of assembly and 0/4 for freedom for non-governmental organizations. Room for political dissent is extremely narrow. However, air pollution is a fundamental crisis and Chinese citizens refuse to be silenced.

In May of 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that an estimated seven million people die annually from the effects of air pollution. These deaths can be linked to the inhalation of fine and small particulate matter. This particulate matter penetrates the lungs and bloodstream, causing numerous life threatening diseases, including: heart disease, lung cancer, respiratory diseases, and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases.[6] According to the WHO, the inhalation of pollutants also has a documented influence on the neurological and physical development of children, negatively impacting cognitive testing and motor development.[7] Those who suffer most tend to be marginalized and low-income groups, especially in the Eastern Mediterranean Region and South-East Asia.[8]

With the threat so evident, many countries are ramping up their efforts to reduce air pollution and China is a notable front runner. Since declaring war on air pollution in 2014, Chinese cities have reduced “concentrations of fine particulates in the air by 32 percent on average” (as of 2018).[9] This was achieved by prohibiting new coal-fire plants in polluted regions, ordering existing plants to limit emissions, shutting down coal mines, and even removing coal-boilers from private homes without offering a viable alternative.[10] These efforts were authoritarian in many respects, but they did produce optimistic results about Chinese life expectancy. According to a study by the New York Times, Chinese citizens can expect to live 2.4 years longer on average if these declines in air pollution persist. If China reaches the WHO’s standards (which the country currently exceeds dramatically), life expectancy could rise another 4.1 years.[11] This begs the question: Can Chinese citizens fight for these extra years?

Ma Jun

Activist and author Ma Jun has been fighting pollution in China for over 20 years. In 1999, Ma published China’s Water Crisis, which was a groundbreaking achievement for climate change documentation in China.[12] This book is frequently compared to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (Click here for Tavaana’s Case Study on Silent Spring) and demonstrates how rapid economic development has devastated China’s environment.

In 2006, Ma founded the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE), a Beijing-based nonprofit that uses public awareness and pressure to enhance environmental responsibility at private and state owned enterprises in China. IPE has built an extensive database of environmental information that shows Chinese citizens not only pollution rates in their area, but which corporations are violating China’s regulatory standards for pollution.[13] The government fines these corporations, but Ma believes they find it “easier and cheaper to simply pay fines for polluting than to clean up their acts.”[14] Public pressure does not go away so easily.

In calling out state owned-enterprises (SOEs), Ma has become one of the few activists in China to continuously challenge an arm of the regime. On the surface, Ma’s actions appear more aggressive than the protests in Chengdu, but they have been received with less repression. Why is this the case?

Ma has contemplated his disproportionate freedom to speak out and shared his thoughts in an interview with the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. His first reason is that his organization has managed to become legally registered in Beijing. This means that when IPE goes after SOEs who are the largest tax-payers in their regions, local governments have limited power to undermine IPEs work. Second, Ma believes that IPEs consistency benefits them: “We stay on course: We build out trust by being consistent.” Next comes compromise. Most notably, IPE has agreed to only use government data. In doing so, IPE acknowledges the leadership of the communist party in the war against pollution. Lastly, Ma emphasizes the importance of collaboration. IPE works with organizations such as the World Resource Institute and this dispersal of work allows for more efficient use of resources.[15]

Campaigns

IPE built its reputation by going after private multinational corporations in China. Most notably, IPE released a report titled “The Other Side of Apple” in 2011, which detailed environmental mismanagement and dangerous working conditions at Apple suppliers in China.[16] Apple ignored this report and numerous warnings from local governments,[17] so IPE published a second report naming more Apple violations and started a social media campaign called “The Poison Apple.”[18] This was a call to action for Apple customers. Eventually, this pressure brought Apple to the table with IPE. Apple has since worked with IPE to improve environmental management and labor conditions in their supply factories.[19]

After building his reputation through successes like this, Ma grew bolder and decided to take on state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Ma knew this would be delicate work and planned accordingly. He pledged to only use government data when examining SOEs, but this data was not freely accessible.[20] In February 2012, IPE submitted a petition to the National People’s Congress requesting the creation of a centralized database of SOE emissions that would be updated in real time. Years of reputation building, alliance building, and raising awareness of pollution paid off. In 2013 the Ministry of Ecology and the Environment (MEP) announced that it would require 15,000 SOEs to disclose pollution data in real time. [21]

This was a significant win for IPE. First, real-time data would make it harder for SOEs to hide their violations. In the past, when SOEs learned about inspector visits they would quickly band-aide their emissions (by diluting waste with water or placing monitors on secondary effluent pipes).[22] Second, it allowed the public to be involved in environmental regulation in China – calling out companies with spiking emission numbers or applauding companies for reducing emissions. To further enhance transparency, IPE translated the government data into a user friendly platform on their website and in a mobile app.[23]

This data disclosure also signaled that members of the regime supported IPE’s efforts. However, the Chinese regime is divided on the issue of pollution and this is a major obstacle for IPE. China’s economic model relies on government investments in industry and infrastructure. Officials in China’s economic bureau encourage economic growth at all costs, incentivizing companies to disregard environmental regulations. Simultaneously, environmental bureaucrats are usings IPEs resources to fine and reprimand violators.[24] As government officials work on these two clashing agendas, the economic team almost always comes out on top and undermines the power of environmental bureaucrats to regulate SOEs.[25] This economic pressure also diminishes the weight of public pressure. SOEs in authoritarian states are designed to respond to the demands of the regime, not the people.

This is not the only way the regime hinders IPE’s work. When one of IPE’s partner NGOs drove around the countryside photographing factories in violation of environmental regulations and sharing the photos on social media, the regime cracked down. The regime ordered Ma to stop the project immediately and Ma complied, recognizing that alienating himself from the regime would only limit IPEs future work.[26] In this example, Ma broke two of his rules: compromise and consistency. First, the project did not rely on government data. To the regime, this was insubordination. The regime needs to be acknowledged as the leader in the war. Second, IPE had been inconsistent and the regime did not see this move coming, which makes the insubordination even more threatening.

Despite these limitations, Ma is able to persist by navigating the regime’s red lines and occasionally he sees these lines waver. Notably, in an unprecedented move, the local government in Lanzhou, Gansu province demanded that their regional branch of the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) apologize to the public for environmental mismanagement and improve their emission rates. Ma applauded this act, saying: “It is rare to see a local government criticize a state-owned enterprise like this, especially when the company was a major taxpayer.” Ma also praised the government’s effort to bring the public into the conversation: “Greater public involvement means more pressure and stronger supervision over some enterprises.”[27] In this example, IPEs model of public pressure on state-owned enterprises to enact change was adopted by Chinese officials. This example demonstrates that the discourse IPE has generated since 2006 is increasingly powerful and able to influence citizens and government officials alike.

Conclusion

Considering IPE’s successes and failures, the cause of repression in Chengdu becomes more clear. During this protest, the regime worked to control the narrative of events, sending an ominous text message that banned air pollution masks in schools. According to Radio Free Asia, students in Chengdu schools received this text message:

“Please do not believe in rumors, and do not spread them… You must put your trust in the government to carry out anti-pollution work… No teachers or students in our school will wear face-masks, without exception.” [28]

This text message is a testament to ordinary pollution activism in China. By writing “You must put your trust in the government”, the regime is asserting their leadership in the war on pollution. The Chinese people do not have the right to form their own opinions and use their own methods of combating pollution. This truth defines Ma’s activism. This is what forces Ma to use government data, create alliances with government officials and watch as economic bureaucrats steamroll environmental efforts. However, Ma has demonstrated that working within the regime’s parameters does not mean he cannot influence the regime. Ma has had success. He slowly pushes at the edges of the regime, tests his limits, and runs down open channels when he finds them.

Learn More

News and Analysis

- “9 out of 10 People Worldwide Breathe Polluted Air, but More Countries Are Taking Action.” World Health Organization. May 2, 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/02-05-2018-9-out-of-10-people-worldwide-breathe-polluted-air-but-more-countries-are-taking-action.

- “Ambient and Household Air Pollution and Health.” World Health Organization. May 2, 2018. https://www.who.int/airpollution/data/en/.

- Bureau, Beijing. “The Artist Protesters in a Polluted City on Edge.” BBC News. December 13, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-china-blog-38298407.

- China Country Report. Report. Freedom House. May 14, 2019. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/china.

- Eaton, Sarah, and Genia Kostka. “Central Protectionism in China: The “Central SOE Problem” in Environmental Governance.” The China Quarterly231 (2017): 685-704. DOI:10.1017/s0305741017000881.

- Ford, Will. “This Activist Uses A Little Shaming And Lots Of Data To Clean Up Chinese Factories.” HuffPost. April 23, 2019. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/majun-ipe-pollution-chinese-factories_n_5cbf2fdce4b0315683fd95f5.

- Foroohar, Rana. “Cleaning Up China.” Time. June 24, 2013. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2145500,00.html.

- Friends of Nature, Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs, Green Beagle, Envirofriends, and Green Stone Environmental Action Network. “The Other Side of Apple.” January 1, 2011. https://www.business-humanrights.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/it_report_phase_iv-the_other_side_of_apple-final.pdf.

- Friends of Nature, Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs, Green Beagle, Envirofriends, and Green Stone Environmental Action Network. “The Other Side of Apple II.”August 31, 2011. http://wwwoa.ipe.org.cn//Upload/Report-IT-V-Apple-II-EN.pdf.

- Greenstone, Michael. “Four Years After Declaring War on Pollution, China Is Winning.” The New York Times. March 12, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/12/upshot/china-pollution-environment-longer-lives.html.

- Haas, Benjamin. “China Riot Police Seal off City Centre after Smog Protesters Put Masks on Statues.” The Guardian. December 12, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/12/china-riot-police-seal-off-city-centre-after-smog-protesters-put-masks-on-statues.

- “Learn More about Ma Jun.” National Geographic Society. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/find-explorers/ma-jun.

- Lin, Xin, Wong Siu-san, and Wong Lok. “China Cracks Down on Chengdu Smog Protests, Detains Activists, Muzzles Media.” Radio Free Asia. December 13, 2016. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/muzzles-12132016132603.html.

- “Ma Jun: Information Empowers.” Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. February 11, 2013. https://www.carnegiecouncil.org/publications/archive/policy_innovations/innovations/000236.

- “More than 90% of the World’s Children Breathe Toxic Air Every Day.” World Health Organization. October 29, 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/29-10-2018-more-than-90-of-the-world’s-children-breathe-toxic-air-every-day.

- Moustakerski, Laura. Publishing Pollution Data in China: Ma Jun and the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs. Report. Case Consortium, Columbia University. 2014.

- “Poison Apple.” Poison Apple | Publishing Pollution Data in China: Ma Jun and the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs – A Journalism Case Study. 2012. http://ccnmtl.columbia.edu/projects/caseconsortium/casestudies/135/casestudy/www/layout/case_id_135_id_987.html.

- Supplier Responsibility: 2018 Progress Report. Report. Apple, Inc. 2018. https://www.apple.com/supplier-responsibility/pdf/Apple_SR_2018_Progress_Report.pdf.

- “Vision and Mission:To Promote Information Disclosure, Serve Green Development, and Bring Back Clear Water and Blue Skies.” About IPE. http://wwwen.ipe.org.cn/about/about.aspx.

- Xin, Liu. “Govt Slams SOE over Pollution.” Global Times. January 12, 2015. http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/901300.shtml.

Images

- Beggerly, Brian Jeffery. Smog over Beijing’s Forbidden City”. September 15, 2005. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beijing_Forbidden_City_Smog.jpg

Footnotes:

[1] Benjamin Haas. “China Riot Police Seal off City Centre after Smog Protesters Put Masks on Statues.” The Guardian. December 12, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/12/china-riot-police-seal-off-city-centre-after-smog-protesters-put-masks-on-statues.

[2] China Country Report. Report. Freedom House. May 14, 2019. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/china.

[3] Xin Lin, Wong Siu-san, and Wong Lok. “China Cracks Down on Chengdu Smog Protests, Detains Activists, Muzzles Media.” Radio Free Asia. December 13, 2016. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/muzzles-12132016132603.html

[4] Beijing Bureau. “The Artist Protesters in a Polluted City on Edge.” BBC News. December 13, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-china-blog-38298407.

[5] China Country Report. Freedom House.

[6] “Ambient and Household Air Pollution and Health.”World Health Organization. May 2, 2018. https://www.who.int/airpollution/data/en/.

[7] “More than 90% of the World’s Children Breathe Toxic Air Every Day.”World Health Organization. October 29, 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/29-10-2018-more-than-90-of-the-world’s-children-breathe-toxic-air-every-day.

[8] “9 out of 10 People Worldwide Breathe Polluted Air, but More Countries Are Taking Action.”World Health Organization. May 2, 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/02-05-2018-9-out-of-10-people-worldwide-breathe-polluted-air-but-more-countries-are-taking-action.

[9] Michael Greenstone. “Four Years After Declaring War on Pollution, China Is Winning.” The New York Times. March 12, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/12/upshot/china-pollution-environment-longer-lives.html.

[10]Ibid.

[11]Ibid.

[12] “Learn More about Ma Jun.” National Geographic Society. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/find-explorers/ma-jun.

[13] “Vision and Mission: To Promote Information Disclosure, Serve Green Development, and Bring Back Clear Water and Blue Skies.” About IPE. http://wwwen.ipe.org.cn/about/about.aspx.

[14] Rana Foroohar. “Cleaning Up China.” Time. June 24, 2013. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2145500,00.html.

[15] “Ma Jun: Information Empowers.” Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. February 11, 2013. https://www.carnegiecouncil.org/publications/archive/policy_innovations/innovations/000236.

[16] Friends of Nature, Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs, Green Beagle, Envirofriends, and Green Stone Environmental Action Network. “The Other Side of Apple I.” January 1, 2011. https://www.business-humanrights.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/it_report_phase_iv-the_other_side_of_apple-final.pdf.

[17] Friends of Nature, Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs, Green Beagle, Envirofriends, and Green Stone Environmental Action Network. “The Other Side of Apple II.”August 31, 2011: p.2 http://wwwoa.ipe.org.cn//Upload/Report-IT-V-Apple-II-EN.pdf.

[18] “Poison Apple.” Poison Apple | Publishing Pollution Data in China: Ma Jun and the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs – A Journalism Case Study. 2012. http://ccnmtl.columbia.edu/projects/caseconsortium/casestudies/135/casestudy/www/layout/case_id_135_id_987.html.

[19] Supplier Responsibility: 2018 Progress Report. Report. Apple, Inc. 2018. https://www.apple.com/supplier-responsibility/pdf/Apple_SR_2018_Progress_Report.pdf.

[20] Laura Moustakerski. Publishing Pollution Data in China: Ma Jun and the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs. Report. Case Consortium, Columbia University. 2014: p.22 http://ccnmtl.columbia.edu/projects/caseconsortium/casestudies/135/casestudy/files/global/135/Ma%20Jun%20final.pdf.

[21] Ibid. 22

[22] Ibid. 24

[23] Ibid. 25

[24] Sarah Eaton and Genia Kostka. “Central Protectionism in China: The “Central SOE Problem” in Environmental Governance.” The China Quarterly231 (2017): 685-704. DOI:10.1017/s0305741017000881.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Will Ford. “This Activist Uses A Little Shaming And Lots Of Data To Clean Up Chinese Factories.” HuffPost. April 23, 2019. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/majun-ipe-pollution-chinese-factories_n_5cbf2fdce4b0315683fd95f5

[27] Liu Xin. “Govt Slams SOE over Pollution.” Global Times. January 12, 2015. http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/901300.shtml.

[28] Xin Lin, Wong Siu-san, and Wong Lok. “China Cracks Down on Chengdu Smog Protests, Detains Activists, Muzzles Media.”