Introduction

For decades, Peruvian women have fought to win justice and protect their rights in a highly discriminatory context. The nadir of human rights in Peru took place between the 1980s and 1990s, as a brutal armed conflict between the Shining Path guerrilla group and the government wreaked havoc on ordinary Peruvians’ lives. Women, particularly those from indigenous and marginalized communities, were subjected to rape by military forces and murder by guerillas, then denied justice. Many women gathered together to organize and speak out; Maria Elena Moyano was one. As president of the women’s federation of Villa El Salvador, she worked to empower women and spoke out against violence, offering a model of leadership that inspired people across Peru. Despite her 1992 assassination by Shining Path, she remains a symbol of courage for Peruvian women who continue the struggle for their rights. Despite continuing challenges, these women have won key legal victories as they work to increase women’s participation in society, protect each other against violence, and secure justice.

Years of Terror: Shining Path’s Guerrilla War

During the 1980s and 1990s, the Maoist guerrilla movement Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso) waged a bloody campaign against the Peruvian state that turned southern and central Peru into a wasteland, leaving 30,000 dead and 600,000 families homeless.[1] Founded in 1970 by philosophy professor Abimael Guzman, the group launched an armed insurgency a decade later, during the first democratic elections since the end of Peru’s military dictatorship. The Senderistas (members of Shining Path) sought support from Peru’s indigenous peasants by claiming they would “destroy the government of the rich and make a government for the poor.”[2] However, it was the poor and indigenous who would suffer most during the chaos that ensued.

Celebrating violence as a “universal law,” essential to “overthrow an old order to create a new one,” Shining Path massacred entire villages, assassinated rural politicians, bombed markets, theaters and restaurants, plunged cities into blackouts, and disrupted food and water supplies.[3] Peruvians were left in terror for years, brutalized not only by Shining Path but also by the state: “Instead of defending us, the military would kill us too. They would jail us, disappear us, rape us.”[4] Meanwhile, the state blamed Shining Path: “The politicians insisted that only the insurgents committed human rights abuses, denying any state responsibility.”[5]

Shining Path financed its campaign of terror by levying taxes on peasant growers of the coca plant, which is processed into cocaine; in return, Senderistas would provide fair prices for their crops and protect them from narcotrafficking violence.[6] As Shining Path used these funds to throw Peru into turmoil, the stage was set for Alberto Fujimori’s 1990 election to the presidency. As an outsider, his surprise victory was driven in large part by dissatisfaction with the white ruling elite and the political establishment that had failed to avert the crisis gripping Peru.

Two years later, Fujimori dissolved the congress and courts and dismantled Peru’s legal system, claiming that they had impeded his efforts to crush Shining Path and fight drug trafficking. He assumed full legislative and judicial powers, ushering in an autocracy that would last until he fell from power in 2000 due to corruption charges.

Throughout the 1990s, security forces waged a systematic campaign of repression, targeting not only Shining Path but also anyone thought to be sympathetic to them, as well as trade unionists, political dissidents, and human rights activists. “We lived those 10 years [of Fujimori’s presidency] in terror,” says one Peruvian. “If you were against the government, you were a terrorist.”[7] State forces committed human rights violations – forced disappearances, killings, rape, and torture – with impunity.[8] In September 1992, Peruvian police captured Guzman, who spent the rest of his life in prison for his role as leader of Shining Path.[9] In his absence, the movement soon fell apart, leaving only small, weak splinter groups.[10]

At the conflict’s end, Peru’s truth and reconciliation commission estimated that of the 70,000 killed, Shining Path was responsible for 54 percent of the death toll, with the government responsible for 37 percent. It was the bloodiest war in Peru since the Spanish conquest in the 17th century, and indigenous Peruvians bore the brunt of it; of the disappeared and dead, 75 percent did not speak Spanish as their first language.[11]

Women were disproportionately subjected to sexual violence. Security forces used rape to punish women they saw as opponents of the state, including university students, teachers, union leaders, and community organizers, and they especially targeted poor, working-class, and indigenous or mixed-race (mestiza) women.[12] Rapists within the military not only escaped punishment, they were actively protected and even promoted.[13] One Defense Ministry official not only excused this (“These boys are far away from their families and suffer a great deal of tension because of the nature of combat”), he also claimed that many women who reported rape were “subversives” attempting to damage the military’s image.[14]

Although rape by Senderistas was much less common, Shining Path frequently threatened and murdered female activists, partly to terrorize their communities into submitting to SP demands and partly as retribution for women’s rights activism. The Senderistas rejected human rights in general as “bourgeois, reactionary, counterrevolutionary rights…a weapon of revisionists and imperialists, principally Yankee imperialists,” and the group accused women’s rights activists of “serv[ing] as an instrument of oppression and retardation of women with the goal of leading them from the path of the people’s war.”[15]

Maria Elena Moyano: Her Fight for Women’s Rights

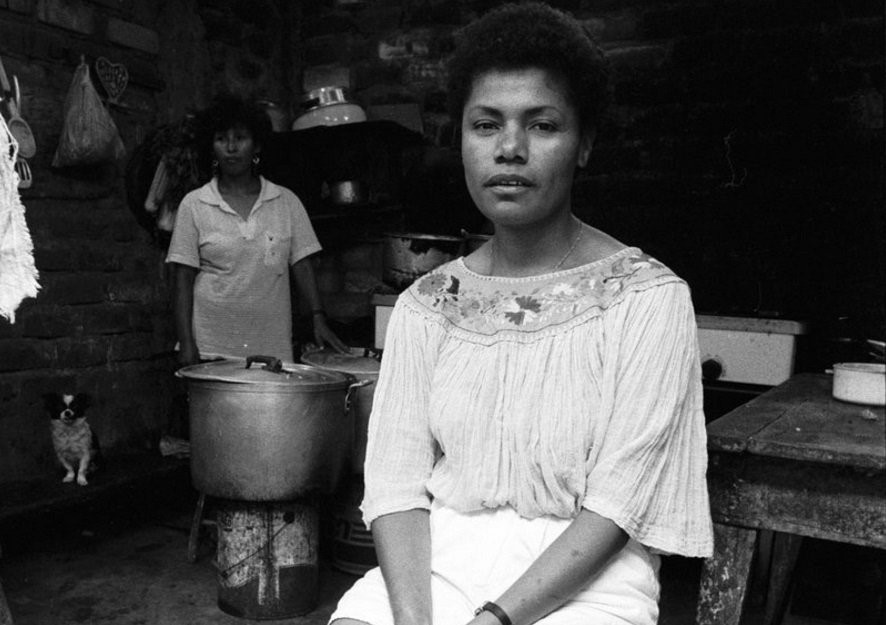

Maria Elena Moyano, known as “Madre Coraje” (mother courage), was an Afro-Peruvian community organizer who fought against poverty, hunger, and terrorism, while working for women’s rights. Her organizing work began in Villa El Salvador, which was originally a shanty town on the outskirts of Lima but, through the work of its inhabitants, ultimately was supplied with electricity, water, and a sewage system. “I learned so much in Villa El Salvador,” Moyano recalled, noting that it was “a concrete example of how a people can organize to secure certain rights from the state.”[16]

After beginning a career as a teacher, Moyano joined a strike calling for a minimum salary; she was elected to the Central Strike Committee as Villa El Salvador’s representative. The committee’s unity and coordination made a deep impression on her; likewise, after becoming director of a mothers’ club, she “became conscious of women’s roles and of their marginalization. Even though they worked outside the home,” she said, “because they were women, their household duties didn’t diminish. I understood, too, just how macho my own husband was.”[17]

In 1979, an organizing committee began to coordinate women’s activities in Villa El Salvador, encompassing community kitchens, committees that planted trees, and efforts to advocate for locals’ rights to philanthropic organizations. Four years later, Moyano helped to form the Popular Federation of Women of Villa El Salvador (FEPOMUVES), which she would ultimately lead as president in the late 1980s. She worked with other women to organize in defense of women’s rights, form sewing cooperatives, and hold health and education workshops.

Another key initiative was the Vaso de Leche program, which provided children with a glass of milk each day, something vital in a country as poor as Peru. After implementing the program and working to make it more successful, the federation successfully advocated for its leadership to be transferred from Lima’s city government to FEPOMUVES community groups in 1987. Politicians doubted the women’s abilities to manage the program’s administration, but the federation quickly implemented new initiatives that improved efficiency and reach. Vaso de Leche was an exemplar of the federation’s approach to community organizing: “We contend that people can learn to govern themselves…so that one day they will be capable of governing at the national level.”[18]

Beyond these community efforts, the federation also monitored the country’s politics in order to respond to national-level issues. Altogether, this work “made it possible for a woman to leave the confines of her home to work in a new, public space” in order to address “issues of nutrition, survival, social conflict, personal problems, and gender issues, such as domestic violence.”[19]

“Prepared to Give Our Lives”: Moyano’s Struggle Against Shining Path

Moyano’s efforts soon attracted opposition from Shining Path, which believed state-supported anti-poverty programs “diminished grievances against the government and…lessen[ed] revolutionary fervor among the poor.”[20] In 1991, Senderistas planted a bomb in a Vaso de Leche milk distribution center, then attempted to pin the blame on Moyano while also accusing her of aiding the military and stealing government funds. She rebutted every charge, declaring, “I could never destroy what I have built with my own hands.”[21]

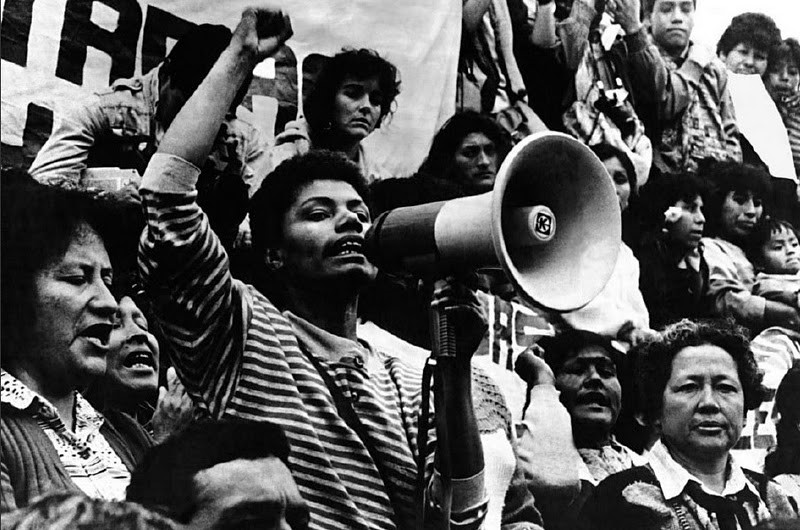

Moyano then called for a popular show of opposition to Shining Path, saying, “we must unite with an organized and strong response… We must very carefully state, to this terrorist group, that it is the Senderistas who oppose the people. Until now, many…have said, ‘Yes, they are compañeros who fight for the people.’ Not any longer. False. They fight against the people.” [22]

As an outspoken opponent of Shining Path, Moyano “represented hope to a country tired of violence and a danger to those who plotted terrorism.”[23] She and fellow members of women’s groups held mass demonstrations against both the Senderistas’ violence and the government’s “Fujishock” economic austerity program which worsened the suffering of the poorest Peruvians. At the end of 1991, La República, one of Peru’s leading newspapers, named Moyano “personality of the year.” Despite knowing that her life was in danger, Moyano declared, “We are not afraid of anyone, and we’re prepared to give our lives.”[24]

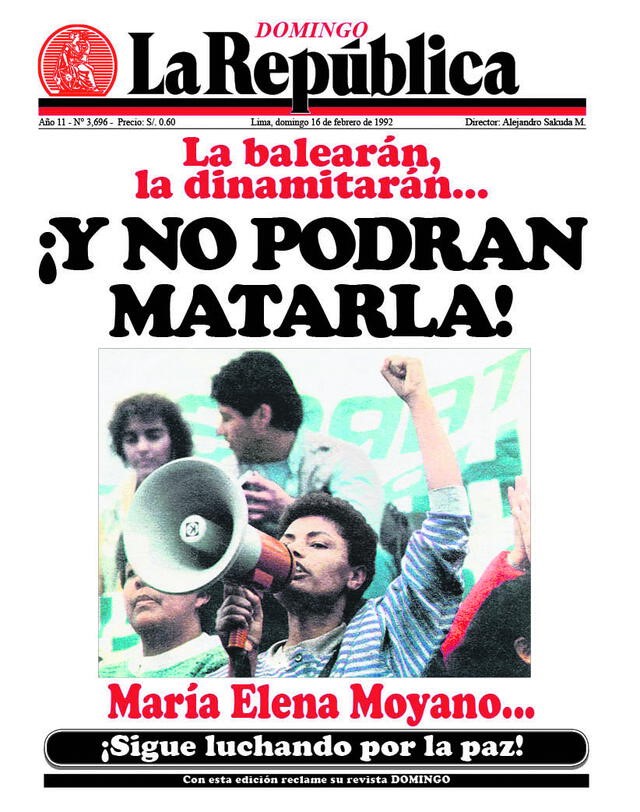

On February 14, 1992, she led a women’s march against violence in Villa El Salvador, where participants carried white banners symbolizing peace. The very next day, Senderistas gunned her down at a community event, ending her life at just 33 years old. They then dynamited her body in front of her young sons.

Still, La República’s headline the next day said, “They will shoot her, they will dynamite her…and they won’t be able to kill her!”[25] At her burial, nearly 300,000 Peruvians marched behind her coffin in a public show of opposition to Shining Path. Her work went on; by the end of the year, FEPOMUVES had organized 112 community kitchens, fed 30,000 people daily, and managed 507 milk committees that had served about 60,000 children.[26]

Not only that, by the end of 1992, the Senderistas’ leader had been captured, and their terrorist activity swiftly dropped off. According to her biographer, this was likely attributable in part to the work of Moyano and her fellow women activists: “María Elena’s murder and the assassinations of other brave women might have finally awakened those who had been on the periphery of the struggle, leaving Sendero without a foothold.”[27]

In 2017, the Peruvian government honored her with the Order of Merit, and the Ministry of Culture granted her the Meritorious Personality of Culture award in recognition of her brave defense of human rights, her community leadership, and her exemplary demonstration of Afro-Peruvian women’s vital contributions to Peru.”[28]

Justice Denied: Violence Against Women and the Peruvian Legal System

Despite provisions for equality under the Peruvian constitution, women continue to be subjected to violence with impunity. Six out of 10 Peruvian women have experienced some form of violence or sexual abuse.[29] In fact, gender-based violence has increased year over year; 137 femicides were recorded in 2022, along with 11,524 reports of missing women. Between January and February 2023 alone, 21,194 cases of violence against women and girls were reported – undoubtedly an undercount, given that under 30 percent of women report such incidents.[30] This distrust of the justice system reflects the “vicious circle” one Peruvian woman describes: “a negligent state response sends an unfortunate message that in Peru you can rape, disappear or kill a woman without consequence.”[31]

Peru’s 1993 constitution guarantees “the right to equality before the law,” prohibiting discrimination based on “origin, race, sex, language, religion, opinion, economic situation or any other reason” (article 2, section 2). In 1994, Peru ratified the Belem Do Para Convention criminalizing all forms of violence against women. In 2017, Law 30364 set up support systems for victims of violence against women.

However, these legal frameworks are not consistently enforced or implemented. Restraining orders against domestic abusers are not enforced; cases of physical abuse are often classified as misdemeanors rather than criminal offenses; and corruption, including widespread bribery, deters victims from turning to the government for justice. In one 2020 case involving the rape of a 12-year-old girl, after the crime was reported, health care workers failed to give her the emergency health kit that rape victims ought to receive under Peruvian law; as a result, she later discovered she was pregnant. Although two men were charged, their relatives provided alibis and a judge let both go free, albeit with some restrictions on their movement. In short, one researcher says, “one can report violence, but nothing will happen.” [32]

Similarly, the state has made little progress in achieving justice for the abuses committed during the armed conflict with Shining Path, including extrajudicial killings, disappearances, torture, and rape. With 70,000 people estimated to have been killed by SP, armed groups, and state officials, the government has only issued 46 convictions in 88 cases.[33]

Legal penalties for violence against women are rarely enforced. The National Institute of Statistics and Informatics reported that between 2015 and 2020, the number of imprisonments for femicides increased from 182 to 604. However, 43.6% of inmates were not actually convicted of a crime, enabling their release and subsequent re-offenses.[34] Moreover, according to the National Penitentiary Institute, as of 2018, 46% of 214 convicted killers of women were serving sentences of 3 to 15 years, below the legal maximum; Law 30819 later changed the minimum sentence to 20 to 30 years.[35]

This culture of impunity is rooted in patriarchy and “machismo” or hypermasculinity; as one activist says, “these attitudes pervade Peruvian society, including government officials tasked with applying the law.”[36] As a result, when women seek justice, they often encounter blame and discrimination. In 2020, for instance, a Peruvian court acquitted a man of rape because his accuser had been wearing red underwear, which the judge claimed “gives the impression that she was predisposed to have sexual relations with the accused.”[37] In such a context, dismantling patriarchal beliefs is a prerequisite for true change.

Feminist Organizing, Challenges, and New Reforms

Between the 1960s and 1970s, feminist groups proliferated in Peru, from the Movement for the Promotion of Woman and the Flora Tristán Working Group to Action for the Liberation of Peruvian Women. They focused on mobilizing women, spreading awareness of their cause through the media, reproductive health, and family education. Their work helped pave the way to the 1972 adoption of article 11 of the General Law of Education; this led to the formation of a committee that oversaw the development and implementation of improved curricula covering family matters and sexuality in schools, reflecting women’s contributions and perspectives. The work to integrate women’s needs into education reform likely influenced the military government’s 1974 Inca Plan, which included a chapter on women addressing gender inequality and calling for reform.

Peruvian women continued their efforts in the 1980s, when they participated in national and global meetings such as the 1985 World Conference to Review and Appraise the Achievements of the United Nations Decade for Women and the biannual Latin American and Caribbean Feminist Encuentros. Following public debate on women’s participation in Congress and the national ombudsman’s office created to oversee civil and human rights, in 1996 the government founded the Ministry of Women and Human Development (known as the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations as of 2012).[38]

Today, the fight for equality continues. DEMUS, a feminist organization launched in 1987, has achieved a number of legal victories. In 2011, for instance, Peru’s Supreme Court approved a measure explicitly recognizing the need to incorporate a gender lens in the judicial process to prevent discrimination when evaluating evidence in sex crime cases.[39] That same year, Law 29819, article 107, made femicides a felony.[40] In 2015, Peru became the first country in Latin America to criminalize sexual harassment with the passage of Law 30314.[41] That year, legislative decree 1428 was issued in order to address forced disappearances.[42]

Media misinformation and a conservative, religious culture contribute to a hostile climate and low levels of support for Peru’s feminists and human rights defenders. Right-wing and religious groups have associated feminism with “gender ideology,” a highly stigmatized concept that has led to broad distrust of efforts to expand women’s rights.[43] As a result of these factors, Peruvian human rights defenders face violence, threats on their life, and even murder. According to Global Witness, Peru is one of South America’s top 3 most lethal countries for human rights defenders.[44]

Conclusion

With decades of struggle behind them, Peruvian women’s resilience and courage has led to the adoption of groundbreaking legal reforms in support of women’s rights. This would not have been possible without the legacy of previous feminists and human rights defenders, like Maria Elena Moyano. A fearless woman who fought against both the state and Shining Path, she serves as an example to all. Along with organizations like the Flora Tristán Working Group and Action for the Liberation of Peruvian Women, she paved the way for future generations who are continuing the fight for women’s rights today.

[1]– The Shining Path: A History of the Millenarian War in Peru, Kenneth Maxwell, Foreign Affairs, January 28, 2009.

[2]– Review: A Jagged Scrap of History, by Rachel Nolan, Rachel Nolan, Harper’s Magazine. May 12, 2020.

[3]– Abimael Guzman, Leader of Peru’s Shining Path Terrorist Group, Dies at 86, Matt Schudel, Washington Post, September 12, 2021.

[4]– Abimael Guzman, Shining Path’s Leader, Died a Year Ago. The Terror He Unleashed on Peru Lives On, Dan Collyns, The Guardian, September 12, 2022.

[5]– La Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos del Perú, Coletta Youngers and Susan C. Peacock, WOLA, October 2002.

[6]– Shining Path, Tupac Amaru (Peru, Leftists), Kathryn Gregory, Council on Foreign Relations, August 27, 2009.

[7]– Act of Treason’: Fujimori Pardon Reopens Wounds for Victims of Peru’s State Terror, Dan Collyns, The Guardian, January 5, 2018.

[8]– Peru/Chile: Serious human rights violations during the presidency of Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000), Amnesty International, December 2005.

[9] Kathryn Gregory, Ibid.

[10] Matt Schudel, Ibid.

[11] Rachel Nolan, Ibid.

[12]– Wartime Sexual Violence in Guatemala and Peru, Michele L. Leiby, International Studies Quarterly, Volume 53, Issue 2, June 2009, Pages 445–468.

[13]– Untold Terror: Violence Against Women in Peru’s Armed Conflict, Human Rights Watch, December 1992.

[14]– Ibid.

[16]– The Autobiography of Maria Elena Moyano: The Life and Death of a Peruvian Activist, Patricia Taylor Edmisten, 2009, Orange Grove Texts Plus, Pages 39-40.

[17]– Ibid, Pages 85-86.

[18]– Ibid, P. 46.

[19]– Ibid, P. 38.

[20]– Ibid, P. 41.

[21]– Ibid, P. 46.

[22]– Ibid, P. 86.

[23]– Ibid, P. 10.

[24]– Ibid, P. 86.

[25]– Cumanana VI – ENG, September 2, 2021.

[26]– Ibid.

[27]– Patricia Taylor Edmisten, P. 47.

[28]– Remembering María Elena Moyano: 30 Years Later, NACLA.

[29]– Vicious Circle’: Femicides in Peru Reveal ‘Crisis’ of Violence, Neil Giardino, Al Jazeera, April 24, 2023.

[30]– Women This Week: Gender Based-Violence Escalating in Peru, Council on Foreign Relations, May 5, 2023.

[31] Neil Giardino.

[32]– The Women Of Peru Are Suffering From A ‘Shadow Pandemic, Maria Godoy, NPR, September 10, 2020.

[33]– Peru, Events of 2020, Human Rights Watch, January 2021.

[34]– Perú: El 43% de presos por feminicidio no tiene condena, Edenilson Román, Cutivalú Piura, January 31, 2022.

[35]– Los deudos del feminicidio: sin Justicia no hay duelo, Ojo Público, July 12, 2020.

[36]– Violence against Women in Peru: Impunity and Injustice, KCL Pro Bono Society, February 9, 2021.

[37]– Ibid.

[38]– 25 años de Feminismo en el Perú, Flora Tristán, Sep 2004.

[39]– Sobre DEMUS: Nuestros logros, DEMUS.

[40]– Normas Legales: Law 29819, El Peruano, 27 December 2011.

[41]– Violence and Discrimination against Women and Girls, Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2019.

[42], Decreto legislativo 1428, El Peruano.

[43], Cinco retos del feminismo peruano para amplificar su mensaje, La Vanguardia, March 8, 2019.

[44]– Human Rights in Peru, Amnesty International.