It was a freezing February day in 1986 East Berlin, and the world-famous Soviet political prisoner Anatoly Shcharansky was about to step out of a plane to freedom after nine years in prison. His KGB escort ordered him to walk straight to the car awaiting him – and Shcharansky refused. “You know that I never agree with the KGB about anything. If you tell me to go straight, I will go crooked.”[1] As KGB agents yelled at him, he ran across the tarmac in a zigzag – one final act of defiance on his way to reunite with his wife after a twelve-year separation. The next day in Israel, Shcharansky would finally complete his long journey to escape Soviet repression. His new life in Israeli politics, as well as his continued human rights advocacy, would now take place under his chosen name of Natan Sharansky.

Born in 1948 in Ukraine, Sharansky grew up as a chess prodigy and top student, but in 1973, he chose to give up his promising scientific career for a far riskier path as a refusenik – a Soviet Jew who was refused permission to emigrate to Israel. In the totalitarian environment of the Soviet Union, refuseniks became pariahs, subject to social ostracism and state persecution. Sharansky soon became the face of the refuseniks’ struggle as they attracted attention and sparked a passionate solidarity movement around the world. His years as a political prisoner turned him into a global icon of Soviet dissent, and the campaign to free him became a key link in the chain of events leading to the Soviet Union’s collapse. Sharansky’s story demonstrates the importance of vocal international support for political prisoners and dissidents, via both grassroots activist movements and political policy that goes beyond rhetoric to tie foreign policy to human rights.

Repression and assimilation: Jewish life behind the Iron Curtain

Well before Sharansky’s birth, Jews across the Soviet Union, from Latvia to Azerbaijan, were subjected to stifling repression. Anti-Semitism had a long history in Russia, but the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop nonaggression pact between the Soviet Union and Germany was a key turning point.[2] It set the stage for the Nazis’ genocide of 2.5 million Jews, or half of the Jewish population, across German-occupied Soviet territory.[3] Once the war ended in 1945, Stalin’s regime brought its powerful machinery of censorship to bear in striving to erase the Holocaust from public consciousness. Meanwhile, in 1940, the regime outlawed all non-Communist groups, thus putting an abrupt end to Jewish community life.[4] In the “black years of Soviet Jewry” following World War II, Stalin targeted leaders of Jewish culture, sentencing prominent writers and journalists to execution or forced labor.[5]

While Soviet Jews were forced by the state to assimilate and suppress their identity as Jews, they were nevertheless discriminated against as Jews, with the old anti-Semitic stereotypes of “Christ killers and money-grubbers” now joined by new state stereotypes of Jews as “cosmopolites whose loyalty to the Soviet regime was always in question.” Ultimately, as Sharansky put it:

Growing up Jewish in the Soviet Union offered nothing positive. No Jewish tradition. No Jewish institutions. No Jewish culture. No Jewish history. No Jewish holidays. No Jewish books. No circumcision. No bar mitzvah. No Jewish language…The only real Jewish experience I had was facing anti-Semitism.[6]

Israel’s stunning victory against the Kremlin-backed Arab states in 1967’s Six-Day War was a watershed moment for Soviet Jews. First and foremost, it sparked a new sense of pride and identification with Israel. As Sharansky wrote, “Seeing how the word ‘Israel’ became something that could boost us—not just diminish us—filled me with a pride and dignity I had never experienced…More and more, I knew that this was the history, these were the people, that was the country, I wanted to belong to.”[7]

Meanwhile, Moscow broke diplomatic relations with Israel, launched an anti-Zionist campaign trafficking in ugly anti-Semitism, and cracked down on Jews with ever harsher punishments for those seeking to emigrate to Israel. This only accelerated their growing alienation from Soviet identity and identification with Israel; as one Soviet Jew said, “I was completely disillusioned with the Soviet Union. I understood that it was almost impossible to change anything here and that it was not my task to try. They didn’t want us there, we were alien, let them deal with it.”[8] The stage was set for a wide-scale movement by Soviet Jewry to reclaim their identity as Jews and emigrate to Israel – a movement that would grow to global proportions.

“Who am I?”: Soviet Jews’ rediscovery of Jewish identity

The foundation and, indeed, pre-condition for Soviet Jewish activism was the development of a collective Jewish identity. Cut off by the Soviet regime from open participation in Jewish community and formal education on Jewish history, Soviet Jews worked together to develop a collective consciousness and reclaim their culture and identity on their own. Paradoxically, the Soviet regime’s punishment of Zionist activists actually laid the groundwork for their network; while doing time in labor camps for infractions as small as sending a letter to Israel, they exchanged addresses with each other so that after returning to their homes, they could coordinate.[9]

One key form of coordination and communication sprang up in the late 1950s as an underground movement to evade Soviet censorship. Known as samizdat, these makeshift publications circulated original essays, petitions, bulletins from the outside world, and literary works that had been banned by the regime. Amidst this cultural revival, Jewish activists founded their own samizdat, such as Evrei v SSSR (Jews in the USSR, 1972-79), which published “Who Am I?” personal accounts from Soviet Jews intended to help foster a broader Jewish consciousness.[10] Other Jewish-founded samizdat covered religious texts and holidays and published historical Jewish writings, re-connecting Soviet Jews to their heritage and traditions.[11]

One of the most crucial samizdat publications in this context was Leon Uris’s 1958 novel Exodus, which recounted the founding of the state of Israel and had a profound effect on Soviet Jews’ perception of themselves and their place in the world. According to Sharansky, “the book was a revelation. It drew me into Jewish history, and Israel’s history…Instead of the short, bloody Soviet history…I joined a story that harkened back to the exodus from Egypt…and would soon lead to my own exodus.”[12]

Meanwhile, activists led “camping” trips to towns in the Pale of Settlement – areas in eastern Europe which had been, to a large degree, the only parts of the Russian empire where Jews had been allowed to live between 1791 and 1917. Participants collected oral histories from the Jews in those areas who had survived the Holocaust, took photographs, and studied Jewish folk art – acting as citizen historians while strengthening their connections to their collective past.[13] Soviet Jews also organized for recognition of the Holocaust, including through gatherings in Riga on each anniversary of the 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising (the largest single revolt by Jews against the Nazis during World War II). Another means of pushing for acknowledgement of the Holocaust was protest poetry, such as Evgeny Yevtushenko’s famous “Babi Yar,” which commemorated the Nazi massacre of tens of thousands of Jews in the Babi Yar ravine in Kiev.[14]

While connecting to their past, Soviet Jews also gradually became more connected to a potential future in the state of Israel – particularly by learning Hebrew. As one Soviet Jew wrote, “Hebrew is not only a means of communication for me – it is a means of self-expression, providing a way to draw closer to the priceless cultural achievements of our Jewish people over its four-thousand-year history.”[15] Hebrew textbooks were prominent among Jewish samizdat, and activists found remarkably creative ways to teach Hebrew classes, such as by holding study sessions on Crimean beaches, under the cover of innocuous family vacations.[16]

As Soviet Jews reclaimed their identity and began to reimagine their future – a future in Israel – they also broke free from the regime’s repression. As Sharansky wrote, “In joining the Jewish people, I discovered that when you have an identity, when you are part of something bigger than yourself, fear for your well-being no longer imprisons you. Putting myself back into my people’s history, into our community, freed me to fight for my rights, for the rights of my fellow Jews, and for the rights of all the people around me.”[17]

From a search for identity to a struggle for freedom in Israel

The natural outgrowth of the burgeoning Jewish identity among Soviet Jews was to make aliya, or emigrate to Israel. As a totalitarian state, however, the Soviet Union was threatened on an existential basis by any disobedience or deviation, however small, from its enforced norms. As such, according to Sharansky, “recognizing the mass desertions open borders could cause, it…couldn’t allow its citizens to choose where to live. That’s why this command-and-control society had no official procedure for emigration.”[18] The only legal way to leave the country was to pursue family reunification and jump through an overwhelming array of bureaucratic hoops.

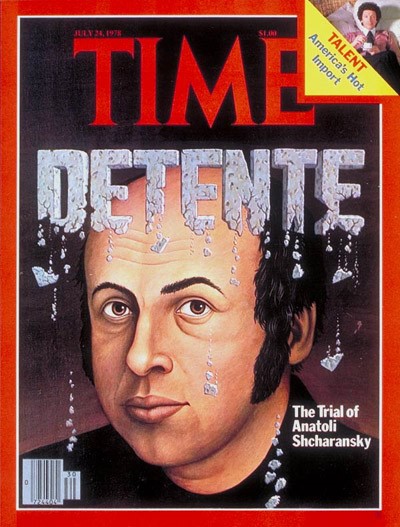

By the 1970s, the total repression of the 1950s had given way to a different type of regime; Brezhnev’s détente and pursuit of economic cooperation with the West left the Soviet Union more vulnerable to international political pressure, and the Soviet government now strove to pretend to respect international norms. As such, the regime refrained from an all-out crackdown on the post-1967 surge of exit visa applications; it let a few through as a show to the outside world, but largely issued mass refusals while also choosing some activists to prosecute, thus making it clear that any Soviet Jew seeking to leave the country would be risking everything.[19]

Approximately 30,000 – 40,000 refuseniks were refused permission to emigrate.[20] The long application process, which required documentation from their work supervisors, their housing offices, and their families, ensured that all of their friends, coworkers, neighbors, and acquaintances, as well as the local KGB office, would be made aware of their rejection of the Soviet way of life.[21] As a result, according to the prominent scientist and refusenik Alexander Lerner, each refusenik was “condemning himself to isolation and persecution until he managed to leave or perished in the attempt.”[22] In a cruel double bind, the state blocked them from employment while also threatening them with prosecution for “parasitism” due to not having a job – a charge that led numerous refuseniks to be sentenced to hard labor in the brutal gulag system of prison camps.[23]

A subset of those refuseniks chose to openly protest. A daring 1970 effort to hijack a plane and escape to the West failed but attracted international attention and led to an increase in the Soviet emigration quota. The refuseniks continued their efforts, whether through petitions, demonstrations, or even – shockingly – sit-ins and hunger strikes in government offices. Timed simultaneously with the World Jewish Conference on Soviet Jewry in Brussels in 1971 and taking advantage of the Soviet regime’s desire to avoid bad press, these sit-ins succeeded in winning re-reviews of 150 refuseniks’ applications, most of which were quickly approved.[24]

Meanwhile, the broader Soviet human rights movement was gripping the world’s attention. In 1968, the famed scientist Andrei Sakharov had gone from the country’s most revered scientist to its most prominent dissident with a manifesto calling for intellectual freedom and critiquing Soviet repression. Although some refuseniks hesitated to get involved in the broader movement for democracy, Sharansky believed the two movements could reinforce each other. He was inspired by Sakharov to gradually overcome his fear and join the refuseniks’ struggle, then the wider human rights movement. Sharansky even became Sakharov’s translator and liaison to the international media.

Sharansky’s English fluency, as well as his “irrepressible charisma and energy,” soon catapulted him to global fame.[25] By 1975, Sharansky was the informal international spokesperson for the refuseniks and the broader human rights movement, meeting regularly with foreign journalists and politicians. Throughout, the goal was straightforward: “to publicize our case and contrast the declared Soviet policy on human rights with our unfortunate reality as Soviet citizens.”[26]

In 1976, in the wake of the Helsinki Accords which committed Moscow to adhering to international human rights standards, Sharansky escalated his activist work, and the attendant risk. He became one of the founders of the Moscow Helsinki Group in order to monitor and shine a spotlight on Soviet human rights violations to the West. Activists across the Soviet Union and the West soon founded more monitoring groups, placing Moscow under unprecedented scrutiny and pressure that would help pave the way for the regime’s ultimate collapse.

“Let my people go!”: The global movement to save Soviet Jewry

The refusenik movement could not have succeeded without support from the outside world – a diverse coalition that included Jewish grassroots, national, and international organizations; civil rights activists; and anti-Communist crusaders. Not only did global supporters provide solidarity that boosted morale among Soviet Jews, they also established a communications network that kept the refuseniks connected to the free world, publicized their plight, and exerted pressure on political leaders to make Soviet human rights a foreign policy issue.

Israel naturally played a key role, albeit largely behind the scenes, in supporting Soviet Jews. Starting in 1951, the Liaison Office, or Lishkat Hakesher, operated out of the Israeli prime minister’s office to assist the refuseniks. This office sent thousands of Israeli tourists to the Soviet Union to encourage Jews there and located ersatz “relatives” whom Soviet Jews could claim as part of their “family reunification” applications.[27] Its dedicated support of Jews outside Israel, including through Operation Entebbe, a 1976 hostage rescue mission in Uganda, played a critical morale-boosting role, assuring refuseniks that “a country thousands of miles away, which most Soviet Jews had never visited, would never stop fighting for us.”[28]

Meanwhile, Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel helped to publicize the plight of Soviet Jews through his 1966 book The Jews of Silence, which called on Jews around the world to help those behind the Iron Curtain: “What torments me most is not the Jews of silence I met in Russia, but the silence of the Jews I live among today.”[29] Galvanized by this cry, Jews around the world organized to help their brethren. Some were haunted by the Holocaust and determined not to repeat their past inaction; others acted from a sense of Zionist-Jewish nationalism; and still others saw the movement as a human rights struggle like others they participated in, such as the US civil rights movement.[30]

From Mexico to France, from the United States to Argentina, the world’s Jews formed committees, held conferences, and marched in the streets, all unified under the demand to “let my people go.” Visiting the Soviet Union as tourists and keeping up a communications network by phone and person-to-person mail, they brought news in and smuggled petitions and letters out.[31] Read aloud over the BBC or Voice of America, these communications from inside the USSR offered a level of protection for their writers.[32] As refusenik Marina Furman said, “If your name was known, it was like insurance.”[33] These writings were also passed to Jewish organizations, then on to politicians, where they had a growing influence on policy towards the Soviet Union.

On this larger level, the refuseniks and their international allies fought to tie foreign policy towards the Soviet Union to human rights issues. In the United States, the Richard Nixon administration was eager to advance détente with no strings attached; meanwhile, the peace movement sought disarmament now, human rights later. Sharansky and his fellow activists sent a different message: “The highest human value is not peace simply, but peace in conditions of freedom. If peace were the ultimate good, dictatorships would exist forever, because no one would endanger his life fighting for basic rights.”[34]

Moreover, they said, Westerners living in freedom were in fact equally threatened by Soviet brutality as Soviet citizens, “since no one can rely on a peace agreement with dictators. The Soviet Union could sign all the treaties in the world while continuing to send its tanks to Prague, its missiles to Cuba, and its paratroopers to Afghanistan. External aggression is part of such regimes’ DNA, an outgrowth of their complete intolerance for internal freedom and dissent.”[35]

Nevertheless, in 1972, the White House was busy making preparations to grant the USSR most-favored-nation status, including major trade benefits, while demanding little from Moscow in return. Then the Soviet Union announced a new “education tax” on Jews seeking to emigrate – stupendously high fees ostensibly intended to pay back the state for free education.[36] This miscalculation provoked outrage in the United States, where even those who had previously been soft on Moscow declared that the USSR was “holding these people hostages of the state.”[37]

Support coalesced across the congressional political spectrum for a new approach that would tie foreign policy to human rights. By 1973, the Soviet Union had dropped the idea of the education tax, and two years later, the historic Jackson-Vanik amendment to the 1974 Trade Act made the removal of sanctions on the Soviet Union contingent on the regime granting Jews freedom to emigrate.[38]

Sharansky would later label this linkage of economic aid to human rights as “the turning point not only in the exodus of the Jews but in the ultimate victory of the West over the Soviet Union in the Cold War.”[39] This groundbreaking move would also pave the way for later human rights-related sanctions such as the 2012 Magnitsky Act, which sanctions individual human rights violators. But the struggle for refuseniks’ rights was still far from over.

Prisoner of Zion: Nine years of imprisonment and international pressure

In 1977, Sharansky was the face of the refusenik movement around the world. He had also become a leader of the broader Soviet dissident movement through the Moscow Helsinki Group. As the group issued report after report and inspired other monitoring groups to spring up around the world, the regime became more desperate to crush them. Sharansky was at the top of their list, as eight KGB agents began following him and a full-page article in a Soviet newspaper accused him of espionage, a capital crime. Clearly, arrest was imminent.

For years, Sharansky’s wife, Avital, had been keeping in close touch with him from Israel; she had immigrated there in 1974, just one day after their marriage. Now, concerned for her husband’s fate, she turned to her friends, rabbis who swiftly established a global network called I Am My Brother’s Keeper in order to support Sharansky and other Soviet Jews. They called Sharansky and told him, “The whole world is watching what is happening with the Jews in Moscow. What happens to you affects all of us. You are now in the center, influencing the entire Jewish world.”[40]

Sharansky was charged with treason – a move that had “few precedents since the days of Stalin.”[41] A wave of international media coverage followed, and in an unprecedented act, the US government denied that Sharansky had ever had any connections to the CIA. Of course, that did nothing to prevent Sharansky’s 1978 sentence to 13 years of forced labor. His final statement at the trial – “I say, turning to my people, my Avital: Next year in Jerusalem…To you, the court, who were required to confirm a predetermined sentence: to you, I have nothing to say” – was printed in newspapers around the world. He had become not just the face of a movement, but an icon, a symbol of Soviet repression whose case was now a cause célèbre across the world.

During his nine years in prison, Sharansky would reflect back on that last phone call. While the KGB no longer resorted to physical torture, it used all its strategies of psychological manipulation to make him feel alone and demoralized. Sharansky reminded himself that he was part of a greater community and a broader struggle – a movement that he trusted would not abandon him. He also mocked his interrogators, telling them jokes and then, when they forced themselves not to laugh, replying, “’You can’t even smile when you want to smile. And you claim that I’m in prison and you’re free?’ I did this to irritate them…But, mainly, I was reminding myself that I was free, as long as I could laugh or cry as I felt.” [42] Rather than focusing on his physical survival, which was at the whims of his captors, he focused on a goal that was within his control: “to live as a free person until my last day.”[43]

Meanwhile, Avital waged a relentless global campaign to free her husband, meeting with politicians and celebrities and coordinating with activist groups around the world. By the 1980s, the refuseniks’ cause had become institutionalized across American and Jewish society. “Solidarity Sunday” marches drew 100,000 people each spring in Manhattan, with politicians competing to be included on the list of speakers. Bracelets inscribed with the names of “prisoners of Zion” – those, like Sharansky, imprisoned for their Zionist activity – became an accessory even adopted by US President Ronald Reagan, who kept one on his desk. Thousands of American Jewish children were paired up with Soviet Jewish children whom they integrated into their bar and bat mitzvah coming-of-age ceremonies and exchanged letters with.[44]

On a political level, Reagan embarked on a crusade against what he called the “evil empire” in a 1983 speech that thrilled Sharansky and his fellow prisoners, who saw it as proof “that the real world was catching on and standing up to the Soviet liars.”[45] Human rights in the USSR were at the top of Reagan’s agenda, and his secretary of state raised the issue of Soviet Jewry in every meeting with his Soviet counterpart.[46] As Mikhail Gorbachev assumed Soviet leadership in 1985 and deepened Soviet engagement with the West, Avital Sharansky and her allies were determined to ensure that this engagement did not leave human rights issues behind.

Indeed, in later years, Gorbachev would recall that “wherever he went in the world, he was confronted by people shouting Sharansky’s name. ‘It wasn’t worth the international price we paid,’ [he] said.”[47] In 1985, Avital burst into a press conference after a US-Soviet diplomatic summit to address the world about her cause. Later that year, she attended a US-Soviet summit in Geneva, where she attempted to deliver a letter to the new Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s wife. At the summit, Reagan told Gorbachev, “As long as you keep [Sharansky] and other political prisoners locked up, we will not be able to establish a relationship of trust.”[48] Just three months later, on Feb. 11, 1986, Sharansky became the first political prisoner released by Gorbachev.

Over the next few years, Gorbachev gradually enacted a new policy of glasnost (openness), dropping censorship of literature and history, moving towards normalization of relations with Israel, ending Sakharov’s six-year exile from Moscow, allowing the founding of non-government organizations, and instituting, for the first time, a formal emigration process.[49] Activists pushed the diplomatic process along, culminating in the historic Dec. 6, 1987 march on Washington. On the eve of a summit between Reagan and Gorbachev, 250,000 people – the same number who joined Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famed 1963 march on Washington – gathered to call on Gorbachev to allow Soviet Jews to emigrate.

The momentum for change in the Soviet Union was now unstoppable. In 1988, the last prisoners of Zion and refuseniks were released, beginning a new Jewish exodus. By the end of the 1990s, over a million Soviet Jews had emigrated to Israel, with another half million to the US and two hundred thousand to other Western countries.[50] In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, and in 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed.

Since then, Sharansky has served in the Israeli Knesset and cabinet, led the Jewish Agency for Israel (which fosters Jewish immigration to Israel), and been a leading advocate for political prisoners around the world. Striving to make sure the world does not forget the lessons of the Soviet Union, he calls on governments to keep human rights high on the agenda throughout negotiations with repressive regimes: “We should not be led into complacency by agreements that promise peace with dictatorships without demanding internal change. If we don’t continue standing up for dissidents and for the shared values they represent, we will soon find ourselves as much at the mercy of their oppressors as they are.”[51] Sharansky’s experience is a testament to the real-life impact such support for dissidents can have – not just in the past, but in the future as well.

Sources

Books:

- Beckerman, Gal. When They Come for Us, We’ll Be Gone: The Epic Struggle to Save Soviet Jewry. United States, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.

- Kosharovsky, Yuli. We Are Jews Again: Jewish Activism in the Soviet Union. United States, Syracuse University Press, 2017.

- Troy, Gil, and Sharansky, Natan. Never Alone: Prison, Politics, and My People. United States, PublicAffairs, 2020.

[1]– Troy, Gil, and Sharansky, Natan. Never Alone: Prison, Politics, and My People. United States, PublicAffairs, 2020.

[2]– Beckerman, Gal. When They Come for Us, We’ll Be Gone: The Epic Struggle to Save Soviet Jewry. United States, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.

[3]– Kosharovsky, Yuli. We Are Jews Again: Jewish Activism in the Soviet Union. United States, Syracuse University Press, 2017, pg xiv.

[4]– Beckerman.

[5]– Kosharovsky, pg xiv.

[6]– Troy and Sharansky.

[7]– Ibid.

[8]– Kosharovsky, pg xv.

[9]– Beckerman.

[10]– Kosharovsky, pg 8.

[11]– Ibid. pp 9-10.

[12]– Troy and Sharansky.

[13]– Kosharovsky, pp 12-13

[14]– Ibid pg 28

[15]– Ibid pg 15

[16]– Ibid pg 234.

[17]– Troy and Sharansky.

[18]– Ibid.

[19]– Ibid.

[20]– Tabarovsky, Izabella. “The Refusenik Exodus from Slavery to Freedom United the Jewish World and Brought Down the Soviet Union.” Tablet Magazine, 8 April 2020. <https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/refusenik-exodus-passover-soviet-union>

[21]– Beckerman.

[22]– Ibid.

[23]– Friedman, Murray, et al. A Second Exodus: The American Movement to Free Soviet Jews. Lebanon, University Press of New England [for] Brandeis University Press, 1999. Pg 203.

[24]– Beckerman.

[25]– Ibid.

[26]– Troy and Sharansky.

[27]– Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29]– Wiesel, Elie. The Jews of Silence: A Personal Report on Soviet Jewry. New York, Schocken Books, 2011. Pg 87.

[30]– Troy and Sharansky.

[31]– Ibid.

[32]– Beckerman.

[33]– Ravitz, Jessica. “Defying the KGB: How a forgotten movement freed a people.” CNN, 30 Dec. 2012.

[34]– Sharansky, Natan. “Why Political Prisoners Matter.” Tablet Magazine, 11 May 2016.

[35]– Ibid.

[36]– Troy and Sharansky.

[37]– Beckerman.

[38]– Troy and Sharansky.

[39]– United States, Congress, Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations. Resolution Recognizing Senator Henry Jackson, commemorating the 30th anniversary of the introduction of the Jackson-Vanik Amendment, and reaffirming the commitment of the Senate to combat human rights violations worldwide. Government Publishing Office, 17 Oct. 2002.

[40]– Ibid.

[41]– Beckerman.

[42]– Troy and Sharansky.

[43]– Ibid.

[44]– Beckerman.

[45]– Troy and Sharansky.

[46]– Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “Jewish leaders from U.S. and Abroad Meet Reagan on Soviet Jewry Issue.” 10 Sept. 1985.

[47]– Keyes, David. “Iran Rejails Political Prisoner Majid Tavakoli.” The Daily Beast, 7 Nov. 2013.

[48]– Troy and Sharansky.

[49]– Beckerman.

[50]– Ibid.

[51] Sharansky.