Since Pakistan was founded in 1947, the country’s women and girls have faced unequal access to education, forced marriage, gender-based violence such as honor killings, and cultural norms enforcing the idea that a woman’s place is in the home. Despite legal provisions and international commitments that theoretically uphold gender equality, Pakistani women are confronted with myriad obstacles in pursuing justice through the law. This, however, has not stopped women from organizing to demand their rights.

After Pakistani laws were Islamized in the 1980s, thousands of women were imprisoned for sexual transgressions, including having been raped. In response, women across the country mobilized to challenge court sentences, raise awareness, and put women’s rights at the top of Pakistan’s political agenda. The struggle became particularly acute as religious extremism rose in the 2000s; when the Taliban seized control over the country’s northwest, Malala Yousafzai became internationally known for her refusal to back down from demanding her right to education – even after being shot. While the fight for full equality continues, the progress that has been made so far is a testament to Pakistani women’s courage and tenacity.

Pakistan’s early years: 1947-77

When India won its independence from Great Britain in 1947, the land was partitioned into two independent countries based on the religious majorities in those areas: India (majority Hindu) and Pakistan (majority Muslim, including modern-day Bangladesh, which later won its independence after the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War).[1]

To counter prevailing cultural norms that segregated women from men across political, educational, and social spheres, Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Muhammad Iqbal, the founding fathers of Pakistan, supported women’s equal participation in public life. In 1944, Jinnah declared, “It is a crime against humanity that our women are [confined] within the four walls of the houses as prisoners. There is no sanction anywhere for the deplorable conditions in which our women have to live. You should take your women along with you as comrades in every sphere of life.”[2]

During this time, the nationalist campaign for independence gave women the space to break traditional norms; “they could cast off the veil, talk to strangers, enter politics, take out processions, shout slogans, hoist flags and face police brutality.”[3] As women claimed a stronger role in public life, Pakistan’s founders envisioned a non-theocratic, liberal democracy and saw women’s rights as perfectly congruent with Islamic principles. As such, when the country was founded, its laws made little distinction between men’s and women’s rights.[4]

Religious scholars (ulema), on the other hand, propagated a vision of a theocratic state wholly rooted in Islamic law in which women’s role in public life would be severely limited.[5] Along these lines, the slogan of the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) Islamist organization, founded in 1941, was “The country is God’s; rule must be by God’s law; the government should be that of God’s pious men.”[6]

Despite women’s role in mobilizing for independence, once that goal was won, they “were pushed back into their homes on the pretext that women’s roles should be within the domestic realm.”[7] Nevertheless, while there was no coherent, organized women’s movement at this time, women still engaged in relief and welfare work, particularly for refugees.[8] In addition to opening girls’ schools and helping women generate income by learning sewing and other skills, the All-Pakistan Women’s Association (APWA) promoted women’s political rights, while being careful not to take a confrontational approach to the state.[9] After widespread demonstrations, the 1948 Muslim Personal Law of Shariat recognized women’s right to inherit property.[10]

Over the next decade, Pakistan became party to the Convention on the Political Rights of Women and the UN Convention on the Consent to Marriage, which prompted passage of a 1961 law that put in place modest limits on polygamy and safeguards for women around divorce.[11]

In 1973, Pakistan’s constitution codified citizens’ equality under the law and prohibited discrimination on the basis of sex. However, reflecting the growing influence of Islamist initiatives such as the JI, the constitution also declared Islam the state religion, required candidates for president and prime minister to be Muslim, and mandated that all laws conform to the Qur’an and sunnah. According to the lawyer and activist Hina Jilani, “All the state could think of to keep themselves a step ahead of the JI and other retrograde Islamic forces was that they had to be more Islamic to overcome them. Women started suffering at this point onwards.”[12]

Islamization under Zia’s military dictatorship

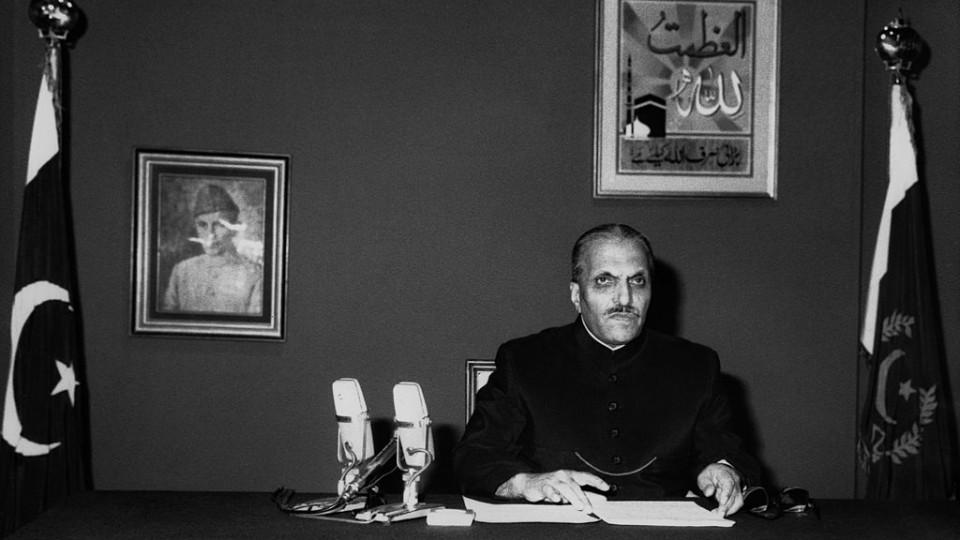

This trend would culminate with an intensive push for Islamization after General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq seized power in a 1977 coup and allied himself with the JI. According to women’s rights activists, “Having assumed power without authority, the army was looking for a means to justify itself and prolong its rule, and it found the perfect excuse in Islam.”[13]

Over his 11-year dictatorship, Zia made sweeping legal, political, and social changes influenced by the hardline Wahhabi school of Islam. A new state-run zakat fund required Muslims to pay a percentage of their income as a donation for the poor (a religious requirement normally fulfilled on an individual basis without a state mandate), and all Pakistanis, including non-Muslims, were forbidden to drink alcohol, with the police conducting home raids to enforce this (often as a means of harassing regime opponents).[14]

Meanwhile, Zia’s military dictatorship dissolved and banned all political parties, enacted full press censorship, revoked workers’ right to strike, and began mass arrests of political party workers and journalists, along with floggings for those who engaged in banned political activity.[15]

Control over women, who were seen as “markers of national morality,” was a key element of this Islamization program.[16] A government campaign against obscenity limited women’s appearance in TV advertisements; women were banned from participating in spectator sports; and they were required to wear chadors in government offices, on TV, and in public schools. A media campaign encouraged vigilante enforcement of conservative dress codes for women, resulting in increased public harassment and even violence towards women.[17] Meanwhile, a new legal architecture of Islamization was raised, including the 1979 Hudood Ordinances, the 1984 Law of Evidence (which prescribed that women’s testimony was worth half that of men’s in certain matters), and the Qisas and Diyat Ordinances. These laws would have far-reaching consequences for women over the next three decades.

The Hudood Ordinances prescribed punishments based on the Qur’an and sunnah for offenses including zina: sexual transgressions including adultery, fornication, and rape. Sex outside legal marriage was now a criminal offense. In the case of adultery, the maximum punishment (singular hadd, plural hudood) was public stoning to death (if the offense was witnessed by four Muslim men of good standing), with discretionary punishment (tazir) being four to ten years’ imprisonment, 30 lashes, and a fine. For simple sex outside marriage, punishment ranged from 30 to 100 lashes. This was also true for rape, which was treated as equivalent to consensual sex outside marriage.In fact, if a woman reported being raped but could not prove it, then the report itself would serve as a confession to zina and she could then be charged with that crime. Moreover, anyone, including an angry husband or brother, could accuse a woman of zina, and that woman would then be arrested and imprisoned – potentially for years since the offense was non-bailable – until she was able to prove her innocence in court. By the time that finally took place, often on federal appeal after a lower-level conviction, these women had spent many years in jail and had become complete social outcasts.[18] Thousands of women were arrested for zina, which was the most common reason for women’s incarceration through the 2000s.[19]

The Qisas and Diyat Ordinances essentially privatized punishment for manslaughter, leaving victims and/or their families to define justice in lieu of the state. For instance, the heirs of a murder victim could accept blood money (diyat) or retribution (qisas, such as eye-for-an-eye punishment). The ordinances’ provisions enabled wealthy offenders to buy their way out of justice; perpetrators of “honor” killings to settle out of court; and men who murdered their wives to pay diyat instead of being subjected to court conviction or a death sentence. As a result, a study found that between 1981 and 2000 in ten Punjab districts, murder rates increased, police closed twice as many cases without an investigation, and convictions at trial dropped.[20]

Women’s mobilization during the Zia regime

In 1981, the zina case of Fehmida and Allah Bux inspired a group of about 30 Pakistani women – feminists, journalists, leftist political activists, and APWA members – to found the Women’s Action Forum (WAF). Unlike previous women’s organizations like APWA, which had been welfare-oriented and pro-establishment, WAF took an unabashedly political approach that not only directly challenged the government but also supported a secular state.[21]

In 1980, the 18-year-old Fehmida, from a lower-middle-class family, had fallen in love with her school bus driver, Allah Bux, and had run away from home to marry him of her own volition. Her angry parents filed a kidnapping police report in order to attempt to force her to return home. Under the HudoodOrdinances, the marriage was found to be invalid based on a technicality (the marriage contract was valid but had not been registered), which meant that the couple was now “living in sin.” As such, in 1981, Fehmida was sentenced to 100 lashes, while her husband was sentenced to death by stoning.[22]

As one of WAF’s co-founders, Anis Haroon, said, “The state wanted to send a message and made an example of this couple of what may happen if a woman, and man in this case, chooses to marry someone of her own choice.”[23]

This case was a wakeup call for many middle- and upper-class women; as incremental progress on women’s rights had been achieved under previous regimes, these women had grown to believe that continued improvements were inevitable. They now realized that all their rights were in jeopardy and that they needed to take action. WAF launched a signature campaign calling for legal protections for women and the lifting of discriminatory provisions; with pioneering women’s rights activist Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan’s name at the top of the list, WAF gained legitimacy that helped them collect a total of 10,000 signatures.[24]

WAF lobbied decision makers, wrote articles for the press, and held seminars with experts to discuss discriminatory laws and debate whether they were truly Islamic. In 1983, WAF organized a march of 300 women in Lahore to protest the Law of Evidence; in response, almost twice as many police officers beat, tear-gassed, and arrested the activists, eliciting wide media coverage that embarrassed the regime. These actions raised awareness of inequality and sparked public debate on these issues. More than that, WAF supported women in fighting rulings under the Hudood Ordinances via the federal appeals process.

Since almost all the women sentenced under the Hudood Ordinances lacked the financial means to challenge their sentences on their own, this aid was invaluable.[25] In one prominent case, the 18-year-old, nearly blind Safia Bibi was raped by her employer and his son. After she gave birth to a baby that soon died, her father filed a rape case, not realizing that her pregnancy would open her up to a zina charge; in 1985, she was sentenced to 15 lashes, three years in prison, and a fine. WAF worked with other women’s groups to file a legal appeal and attract international attention by inviting global women’s groups to lobby for Safia, who was ultimately acquitted by the Federal Shariat Court.

Meanwhile, other women’s groups took action. The Tehreek-e-Niswan organization used the arts in order to reach a wider audience, staging small public plays or dance performances followed by discussions between the actors and audiences on women’s issues.[26] The attorneys founded Pakistan’s first all-female law firm, AGHS, in order to provide free legal aid to women, religious minorities, and anyone whose human rights were violated.

By the time Zia died in 1988, even though women’s groups had not been able to repeal laws like the Hudood Ordinances, they had succeeded in regularly overturning zina punishments upon appeal and had put women’s issues front-and-center within the national political discourse. In fact, when elections took place after Zia’s death, every political party, even the JI, mentioned women’s rights in their platforms. According to Jilani, “We put women on the political agenda in Pakistan.”[27]

Setbacks under democracy and dictatorship

After the liberal Pakistan People’s Party won the 1988 election, Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto became the first democratically-elected female leader of a Muslim-majority country. However, women’s rights activists’ hopes for major change were soon dashed. Well aware of the religious right’s ongoing power, liberal politicians did not even make an effort to repeal any of Zia’s discriminatory laws. A few small, promising steps were taken, such as the 1989 creation of a First Women’s Bank to provide credit to women and the 1996 ratification of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

However, throughout the 1990s, it was clear that the CEDAW commitments would remain on paper only. Honor killings increased, with the perpetrators routinely receiving social and state support and escaping punishment. Acid attacks, forced marriages, and exchanges of girls in order to settle tribal disputes continued. Right-wing extremists threatened and harassed activists such as Jahangir, even issuing religious edicts (fatwas) offering rewards for their assassination.

The rise of religious extremism would only intensify after Pervez Musharraf came to power in a 1999 military coup. While Musharraf promised “enlightened moderation,” he also facilitated the rise of far-right religious parties “to brandish to the West the threat of Islamic extremism and to show the United States that the only alternative to military rule is the rule of the mullahs.”[28]

In 2002, a coalition of extremist religious parties, the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA), won elections and took almost total control of the country’s northwest on a platform that “promised a new world order to resist the worldwide conspiracy against Muslims.”[29] In the northwest, gender segregation was swiftly enforced in education and healthcare, and a public campaign decried family planning as a tool to limit the world’s Muslim population. Female dance, music, and other public arts performances were banned, and the province’s only women’s crisis center was shut down.

The Supreme Court and National Assembly acted as checks and balances on the MMA’s efforts, but it soon became clear that no government forces could hold back Pakistan’s Talibanization. By the time Musharraf stepped down in 2008, the Pakistani Taliban had taken control over much of Afghanistan’s northwest – including the Swat valley where Malala Yousafzai lived. At that time, she was just an 11-year-old girl who loved school and who sometimes spoke at local events with her father, an education activist who ran the school she attended. Within just a few years, however, the whole world would know her name.

Malala Yousafzai: Speaking out for girls’ right to education

Through the 1980s, support from the Pakistani government, the Persian Gulf states, and US intelligence for the mujahideen’s fight against the Soviets in Afghanistan had turned the Afghan-Pakistan border into a base for militants. The influence of Wahhabi Islam via Pakistani migration to the Gulf, strengthened by Saudi funding to Pakistani madrasas (religious schools), fueled increasingly extremist forms of Islam in Pakistan’s northwest. In 2007, 40 fundamentalist groups united under the umbrella Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) organization, aiming to expel Western forces from Afghanistan and impose sharia law in Pakistan.

That year, the Pakistani Taliban assassinated Benazir Bhutto and seized control over Swat, launching a reign of terror as well as a military conflict that displaced hundreds of thousands. The militants killed tribal leaders, military, and police; forced local men to join them or executed them as public examples; forced girls into marriage and banned women from working or going out in public without a male family member; and blocked access to healthcare including polio vaccinations and birth control. Across the country, however, politicians were hesitant to condemn this repression for fear of appearing to be in league with the West.

TTP also targeted education, particularly girls’ schools. By the end of 2008, about 400 schools had been blown up, and still more had been shut down. At this point, TTP declared that starting the next month, girls must not go to school. The 27 girls in Malala Yousafzai’s class swiftly dwindled to a group of just ten. However, Malala remained resolute: “We believed school would start again. The Taliban could take our pens and books, but they couldn’t stop our minds from thinking.”[30]

Not long afterwards, a BBC Urdu correspondent asked Malala’s father if he knew of a girl who could write a diary about life under the Taliban. Malala, who had already done some local TV interviews, volunteered, and soon national and even international media outlets began republishing her words. Meanwhile, the New York Times filmed a documentary featuring Malala and her family, drawing more global attention to the plight of those living in Swat.

Over the next several years, Malala continued her education and also continued to speak out: “How dare the Taliban take away my basic right to education?”[31] As she did so, she received more and more recognition: prizes, media interviews, meetings with politicians. She also began to receive death threats. The Pakistani military had regained control over Swat in 2009, but the Taliban continued to target anyone who spoke out against them.

On October 9, 2012, they made good on their threats; gunmen stopped Malala’s school bus and shot her in the head, along with two of her schoolmates. The Taliban openly declared, “We carried out this attack, and anybody who speaks against us will be attacked in the same way.”[32] The world responded with outrage, but as her international stature grew, so too did conspiracy theories and defensive rhetoric in Pakistan, where “it was almost impossible to express support for Malala…without seeming an apologist for US atrocities or Islamophobia.”[33]

After recovering from her injuries in the UK, Malala and her family remained in Birmingham. She has continued her advocacy for girls’ right to education, co-founding the Malala Fund in 2013 to work towards this goal. The following year, Malala received the Nobel Peace Prize, becoming the youngest Nobel laureate ever at the age of 17. She declared:

The terrorists thought they would change my aims and stop my ambitions, but nothing changed in my life except this: weakness, fear and hopelessness died. Strength, power and courage was born … I am not against anyone, neither am I here to speak in terms of personal revenge against the Taliban or any other terrorist group. I’m here to speak up for the right of education for every child. I want education for the sons and daughters of the Taliban and all terrorists and extremists.[34]

Demanding justice for rape survivors

Against the backdrop of Pakistan’s Talibanization, limited progress was finally made on reforming the Hudood Ordinances. After decades of demands for change from women’s rights activists, circumstances aligned to push the government to take action. In the 2000s, rape survivors began speaking out openly, giving media interviews, leading protests, and tenaciously pushing their cases through the justice system.

Mukhtar Mai became known around the world when she refused to give up seeking justice after being gang-raped in 2002. The local tribal council (jirga) in her southern Punjab village had sentenced her to this punishment in retaliation for her 12-year-old brother’s alleged sighting alone with a woman from a higher caste. Women in Mai’s position were expected to commit suicide – but instead, she made a police report the next week. Local media coverage drew attention from activists who supported Mai in organizing rallies and obtaining legal representation. The case dragged on for years, during which Mai founded schools in her village and refused to leave her home, saying, “I will stay and fight for the rights of the women and men of my village and will continue to run my school to spread the light of education.”[35]

After six of the accused were sentenced to death and eight others were acquitted, that sentence was overturned; the government appealed, and finally, in 2011 – almost a decade after the crime – the Supreme Court acquitted 13 of the accused men, commuting the 14th man’s sentence to life imprisonment. The case was a crushing reminder of the inequity in the Pakistani legal system, which fails to conduct investigations or dispense justice in a timely manner, even as it swiftly deals with other issues; subjects survivors to an unrealistic burden of proof; and is vulnerable to behind-the-scenes influence from powerful individuals such as the tribe that violated Mai’s rights.

Likewise, Shazia Khalid’s 2005 rape case demonstrated the monumental obstacles facing survivors, as the government forced Khalid and her husband out of the country to keep her from pursuing justice. Moreover, in a Washington Post interview that same year, Musharraf claimed that rape “has become a moneymaking concern. A lot of people say if you want to go abroad and get a visa for Canada or citizenship and be a millionaire, get yourself raped.”[36] The ensuing outrage led Musharraf to deny he had ever said such a thing.[37]

Despite the lack of justice in Mai and Khalid’s cases, these courageous women became role models. The international spotlight they shone on injustice embarrassed Pakistan’s government into attempting to repair the country’s image. The time had finally come for the Hudood Ordinances to be reformed, even if in a limited fashion.

In 2006, the Women’s Protection Act amended the zina laws to make rape an offense under Pakistan’s Penal Code rather than the Hudood Ordinances; as such, rape reports can no longer expose victims to a charge of zina if they are unable to prove they were raped. Additionally, zina can no longer be punished by the maximum penalties (hudood) under Islamic law. The Act also addressed false accusations, mandating that failing to fulfill the evidentiary requirements for zina accusations would lead to punishment; additionally, a husband’s false zina accusation were now grounds for a woman to seek divorce. Finally, a new clause implicitly recognized marital rape as a crime, and the Act also mandated that marriage of girls under 16 be considered rape.[38]

More incremental legal improvements have since been made to increase protection of women’s rights. In 2020, an amendment to the Companies Act made the process of opening a business the same for men and women, who previously were required to provide their father or husband’s information when incorporating their own business.[39] In January 2022, the Protection Against Harassment of Women at the Workplace Bill expanded the definition of harassment to cover any gender-based discrimination, extended protections to students and domestic workers, and streamlined the complaint process.[40] Although there is still a long road ahead to achieve full gender equality in both policy and practice, women like Malala Yousafzai and Mukhtar Mai show that when women demand change, progress is possible.

[1] “History of Pakistan.” High Commission for Pakistan London.

[2] Mumtaz, Khawar and Farida Shaheed (eds). Women of Pakistan: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back? The Bath Press, 1987. Pg. 7.

[3] Saigol, Rubina. “Feminism and the Women’s Movement in Pakistan: Actors, Debates and Strategies.” Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2016. Pg. 8.

[4] Weiss, Anita. “Moving Forward with the Legal Empowerment of Women in Pakistan.” United States Institute of Peace Special Report 305, May 2021. Pg. 3.

[5] Mumtaz and Shaheed pp 8-9.

[6] Khan, Ayesha. The Women’s Movement in Pakistan: Activism, Islam and Democracy. I.B. Tauris, 2020. Pg. 21.

[7] Khan, Leena Z. “Women’s Action Forum (WAF) – Women’s Activism and Politics in Pakistan.” Institute of Current World Affairs (ICWA) Letters – South Asia, 2001. Pg. 4

[8] Saigol pg. 9

[9] Ibid. pg. 10.

[10] Ibid. pg. 8.

[11] Weiss pg. 4.

[12] Ayesha Khan pg. 23.

[13] Mumtaz and Shaheed pg. 16.

[14] Ayesha Khan pg. 56.

[15] Ibid. pg. 58.

[16] Ibid. pg. 129.

[17] Ibid. pp. 58-9.

[18] Lau, Martin. “Twenty-Five Years of Hudood Ordinances – A Review.” Washington and Lee Law Review 64:4, 2007. Pg. 1,296.

[19] Ayesha Khan pp. 62-3.

[20] Ibid. pg. 71.

[21] Ibid. pg. 77.

[22] Leena Khan pg. 6.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Burki, Shireen. The Politics of State Intervention: Gender Politics in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran. Lexington Books, 2013. Pg. 60.

[25] Burki pg. 61.

[26] Ayesha Khan pg. 84.

[27] Ibid. pg. 113.

[28] Ibid. pg. 173.

[29] Ibid. pg. 174.

[30] Yousafzai, Malala with Christina Lamb. I Am Malala: The Story of the Girl Who Stood Up for Education and was Shot by the Taliban. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2013.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ayesha Khan pg. 212.

[34] Nichols, Michelle. “Pakistan’s Malala, shot by Taliban, takes education plea to U.N.” Reuters, 12 July 2013.

[35] Ayesha Khan pg. 221.

[36] Kessler, Glenn and Dafna Linzer. “Musharraf: No Challenge from Bush on Reversal.” The Washington Post, 13 Sept. 2005.

[37] Kessler, Glenn. “Musharraf Denies Rape Comments.” The Washington Post, 19 Sept. 2005.

[38] Ayesha Khan pg. 229.

[39] Hamel, Iva et al. “Legal Reform in Pakistan.” Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative, 2021.

[40] Ijaz, Saroop. “Pakistan’s New Law Aims to Protect Women in Workplace.” Human Rights Watch, 20 Jan. 2022.