Introduction: The Malaysian Mosaic and the Multiethnic Challenge

For centuries, diverse ethnic groups and religions have crossed paths in the Malayan peninsula, making the region’s politics – and its transition to democratic governance – subject to competing interests that could easily have stymied the establishment of a constitutional monarchy. Nevertheless, after Britain gained a colonial foothold in the area in the 19th century, the various communities within Malaysia – from the sultans and aristocracy to popular movements, and from the Malay majority to the Chinese and Indian minorities – ultimately succeeded in establishing a fully-fledged federal constitutional monarchy. In a region often riven by political strife and autocracy, Malaysia, despite its shortfalls and challenges, has stood as an example of democratic governance, political stability, and sustainable economic growth.

Late Colonial Era to World War I: Colonial Vassals

For centuries, the area now known as Malaysia – the Malay Peninsula, a portion of the island of Borneo, and islands off Borneo’s coast – was a crossroads for diverse cultures and religions. As a key route on the maritime silk road, Malaysia attracted traders from across Asia and the Middle East, who both passed through the area and settled down to join the native Malay population, bringing with them influences from Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam. By the 15th century, the Chinese empire and the kingdom of Siam (now Thailand) were competing for vassal clients among the region’s kingdoms, with China winning sway over the kingdom of Malacca on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. This strategically-located kingdom soon adopted Islam, which spread from the king and the elites to the broader population, then on to neighboring kingdoms thanks to Malacca’s influential position as a locus of power and wealth. The Islamization of the region marked a religious and cultural paradigm shift away from Hinduism, Buddhism, and other non-Abrahamic Asian religions.[1]

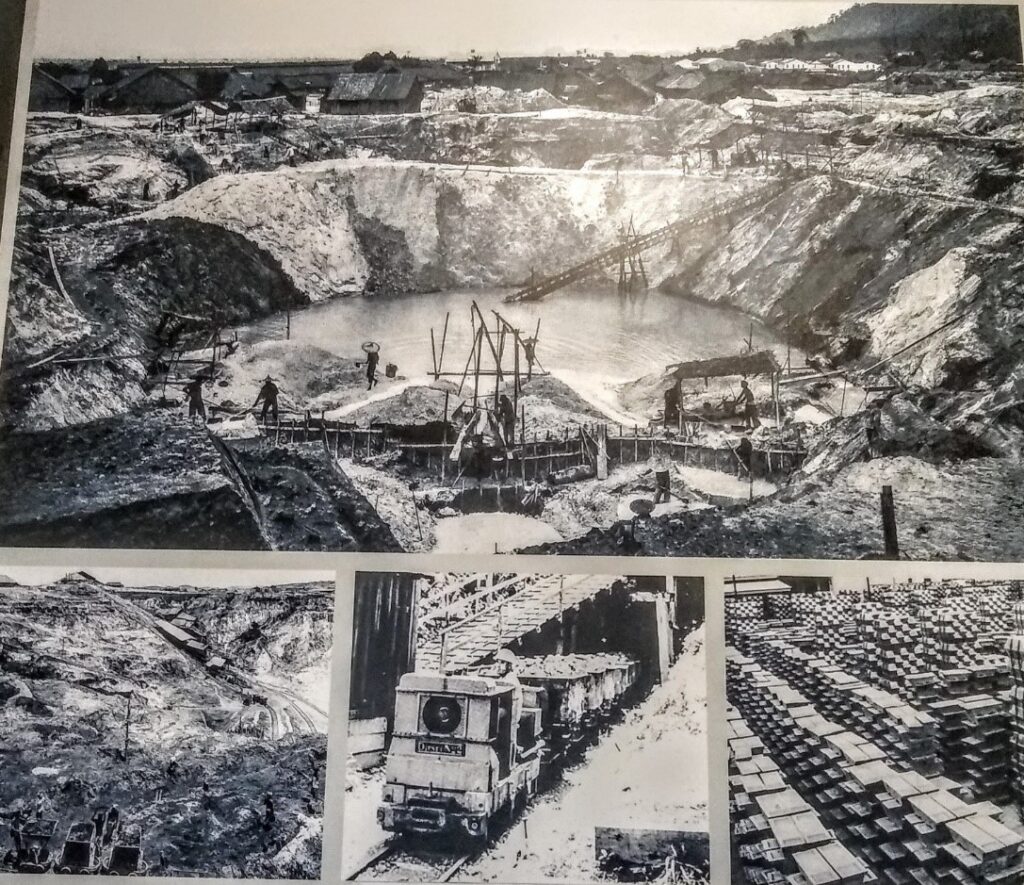

While this religious transition was underway, European explorers began turning their attention to Malaysia as a maritime route to Asia as well as a source of spices, tin, and other resources.[2] In 1511, the Portuguese seized Malacca, giving rise to a power struggle between other Malay kingdoms to fill the void left by Malacca. By the 17th century, the balance of power in the region had shifted towards the Dutch and their ally, the Johor sultanate; in the following century, Siam extended its control over north Malaysia.

With industrialization driving a spike in demand for resources from around the world, Britain began to grow more interested in Malaysia for its strategic location for British trade, beginning in the late 18th century. Meanwhile, friction between – and within – the diverse groups in the Malaysian peninsula was increasing, as the growing Chinese population and their Malay neighbors clashed both internally and with each other over the wealth to be gained from local industries such as tin. Growing increasingly concerned over this instability and its economic ramifications, the British began exerting more direct control over Malaysia.

By the 1870s, Britain’s colonial administration was managing the government across a number of Malayan sultanates. Ultimately, this was done via British “resident ministers,” or advisors, who exerted power while being assigned to sultans who retained symbolic roles. In 1895-96, four Malayan states (Perak, Pahang, Selangor, and Negeri Sembilan) were brought together in a centralized group of federated states, which were subject to more direct British control than the unfederated Malay states (Johor, Kelantan, Kedah, Perlis, and Terengganu).

Having learned from their bloody experience with the 1857-58 Indian Rebellion, the British made concessions to win over local elites, including through pensions to the aristocracy; to protect some of the authority of the ruling sultans; and to grant legitimacy to the pre-colonial system of Islamic laws and court jurisdiction over matters of personal status and inheritance, while still imposing a British-style legal system.[3]

Although some armed resistance to colonialism did arise in the late 19th century, the British’s efforts to co-opt the local elites worked in their favor, as did their military might.[4] Overall, anti-colonial sentiments at this time were relatively limited to mid-ranking authorities, though local populations tended to perceive their discontent as merely self-interested longing to restore their lost status.[5] Some British officials believed some rebellions, such as the 1890-95 revolt in Pahang, were due to some sultans’ dissatisfaction with their weakened position.[6]That said, some sultans, particularly those of the unfederated Malay states such as Johor, were able to operate with a semblance of independence within the British Malay order, as demonstrated by Sultan Abu Bakar of Johor’s establishment of the first written constitution among the Malay states in 1895.[7]

At the popular level, in contrast to the Dutch colonial rulers of Java and Sumatra who had banned the hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca), the British not only allowed the hajj but also accommodated Muslim Malaysians’ annual voyages to Mecca via the British naval monopoly of Thomas Cook & Son.[8] This was another concession that helped limit the spread of anti-colonial opposition, as much of the population did not find the British presence in the area to be very objectionable.

Beginning in the early 20th century, anti-colonial sentiments evolved out of a growing ideal of pan-Islamic identity that was influenced by Malays’ hajj encounters with other pilgrims, the return of Malay students from Middle Eastern Islamic schools, and the pioneering non-Malay Chinese and Indian press, which increasingly critiqued British policy and raised political consciousness among readers.[9] Meanwhile, as Malay civil servants increasingly received a modern education, local capacity for administration grew, paving the way for eventual self-rule.[10]

Dragged-out Decolonization: Transition to Federated Protectorates

Until World War I, the British empire’s success at coopting the sultanates as their rentier clients outweighed any nascent nationalist call for self-determination. However, at that point, two key developments persuaded the British colonists that the regional status quo was increasingly untenable. In the wake of World War I, Britain’s fiscal coffers were almost empty, and its government was desperate to cut back on the administrative and defense budgets of its many colonial territories. Moreover, unrest was on the rise among the British empire’s far-flung subjects; they were increasingly demanding home rule or outright independence as Woodrow Wilson’s “self-determination” rhetoric echoed globally.[11]

Britain thus began a long process of decolonization that extended decades past the interwar period, accelerating at the dawn of the Cold War. Even as the British pursued decolonization, they still hoped to implement a “Grand Design” whereby the British Malay colonies would preserve British trade interests and act as a bulwark against the expansion of communism in the region.[12]

Interwar Era to 1945: Rise of Urban Working and Middle Classes and Civil Society

Between 1910-21, the increasing migration of Chinese workers to the Malay peninsula proved to be a turning point in the region’s identity politics. Having witnessed the deference (however limited) paid by the British to Malay sultans, Malay-born Chinese communities began expecting more participation in local affairs. From the 1930s onwards, various ethnic-based community groups and associations began to form and to voice their demands for improvement in a host of areas, from equal opportunity in the colonial administration’s civil service to better conditions for workers and improved municipal services.[13] Malay, Indian, and Chinese groups included community associations, urban civil society organizations, newspapers, and business and professional associations, and each group pursued their respective demands for the betterment of their lot in the greater colonial order.[14] These efforts stemmed in part from the British administration’s pro-Malay policies.

Meanwhile, a local Muslim youth association, Kaum Muda,began promoting the value of political freedom via religious publications such as Al-Imam magazine, founded in 1906. Newspapers were flourishing as a megaphone for many groups demanding change in local governance and the British colonial administration. Indeed, these newspapers galvanized public opinion to the extent that the British restructured the federal council they had formed prior to the war. Its original purpose had been to give representation to British planters and businesses, but now its membership was adjusted following media demands that the council include Indian and Chinese representation.[15]

As the British empire emerged from World War I shaken, yet not completely bankrupt, it used its policy of coopting local populations to simultaneously meet its need to fill lower-ranking administrative positions in the Malayan Administrative Service (MAS). Having achieved great success in coopting local elites, the British now began working to coopt the subjects of the sultanates as well. The formation of local legislative councils with limited power to oppose British authorities allowed for some semblance of native participation in their own affairs.[16] Additionally, the British began to integrate both aristocratic and educated youth, including college graduates, into their administrative service. Indeed, decades later a number of these college graduates who started their public service careers in MAS would go on to found the nationalist political party United Malays National Organization (UMNO).[17]

The Rise of Malay Working Professionals and Colonial Civil Servants

Thanks to the decentralized nature of British indirect rule, even though both the federated and unfederated Malay states were groups of protectorates, the federated states enjoyed their own state councils, laws, court systems, and supreme courts – all as a burgeoning Malay elite in those states began to develop a sense of common identity through history, religion, culture, and geography.[18] When the British sought to centralize all administration of both federated and unfederated states in 1930 in Kuala Lumpur, the unfederated sultans revolted in fear that it would reduce the limited autonomy they still retained. As a result, the British ultimately implemented their plans in a more piecemeal manner. This provided a window of opportunity for the professionalization of the Malay public service; by the dawn of World War II, the civil service was staffed by educated and professionally successful employees who believed their administration was ready for self-rule.[19]

The First Transition, 1945-48: Negotiating Independence

The Japanese occupation of the Malayan archipelago between 1941-45 marked a watershed moment for both elite and popular attitudes towards decolonization in the region. Even though the Japanese presented themselves as liberators under the banner of pan-Asianism, ultimately, the local population saw little difference between them and the British in terms of colonial imperialism. Additionally, Japanese occupation policies, including favoritism towards the Malay population, sparked increased nationalism among each ethnic group in the area.

1946-48 was yet another turning point for nationalist and populist politics in Malaya. Clement Attlee’s Labor government was bent on granting home rule or independence to many British colonies, and Malaya was no exception.[20] If Malay states had been dominated by the British residents-general and the sultans until this point, from this point onwards they would be dominated by the aristocratic, elite political leaders of right-wing nationalist parties.

In 1946, Britain announced its plan to unify all the Malayan states under a new, centralized Malayan Union – and met with a swift and negative reaction. Malaya’s various nationalist factions, dominated by the sultanate aristocracy, followed the sultans’ lead, refusing to sign away their powers to the central government. The opposition soon took the form of national resistance, as the people did not trust the new proposed order and preferred to stick to their traditional states. Hence, the British withdrew this proposal. The elite, which had lagged behind the public in calling for outright independence, now formed the United Malays National Organization (UNMO). The Indian community formed the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC) at the same time and by 1949, the Chinese community had followed suit with the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA). After dropping the proposed union, the British engaged UMNO in negotiations.

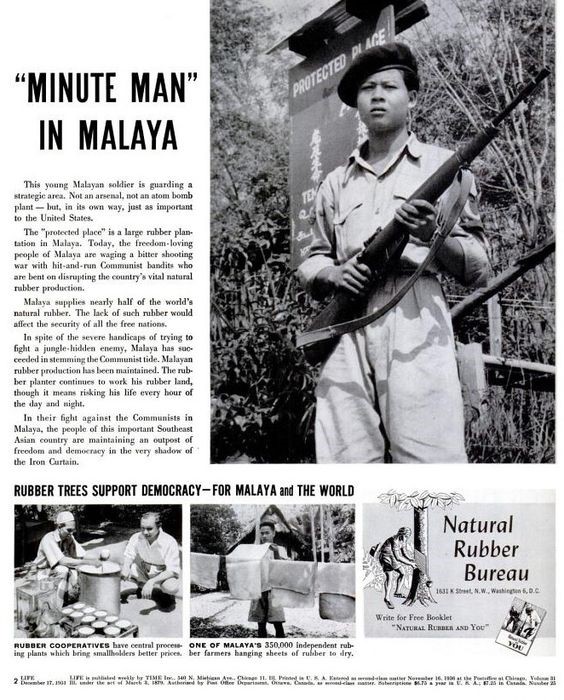

Meanwhile, the region’s communists were preparing for a guerilla war against the British. As tin and rubber had become the main revenue-generating commodities in British Malaya, communism had won over many Chinese workers, who joined Malay Communist Party legions which had collaborated with a handful of British special forces and waged a grueling guerrilla campaign against the Japanese in the early 1940s.[21] Although the British showered the communist guerrilla leaders with medals and recognition, the 1946 onset of negotiations between the British and UMNO for gradual independence was an ominous signal to the communists that the country was taking a turn to the right. They began retreating to the jungle to dig out the arms they had buried after the war and regroup. In 1948, the communists launched a guerrilla war to win independence under communist leadership. Labeled the Malayan Emergency by the British, the insurgency continued until 1960.[22]

As urban populations joined the various parties fighting for a place at the negotiation table, newspapers became a key medium of expressing competing views on the structure of post-colonial Malaya.[23] As the Malayan aristocracy at the helm of UMNO presented themselves as the true champions of Malay self-determination, they blamed the sultans for the colonial-era treaties that had privileged British interests over Malayan ones. In turn, the sultans joined the nationalist movement, albeit a more conservative variation of it.[24]

For their part, the diverse populations of the area feared and distrusted each other, with Malayan nationalists determined to protect their interest from Chinese and Indian communities even as those minorities feared being relegated to second-class status.[25] There was also a degree of opposition to the concept of a universal Malay identity; for instance, in 1946, Johor civil servants launched mass protests in opposition to their sultan, accusing him of having violated the state constitution by agreeing to join the negotiations with the British for the formation of a Malay Union.[26]

As negotiations dragged on from 1946 into 1947, the All-Malay Council of Joint Action, another coalition of activist groups, proposed a popular constitution wherein Islam would be the official religion and all the sultanates would be retained with their respective jurisdictions within the federation.[27] The result of the 1946 negotiations was the establishment of the Federation of Malaya in February 1948. This new federation provided special guarantees for the rights of the Malay population, including the sultans, and contributed to the subsequent formation of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MLNA) by the communists, who would wage war on the British and the newly formed federation.

The Second Transition, 1948-1957; From the Malayan Emergency to Constitutional Dialectics of Malayan Independence-Merdeka!

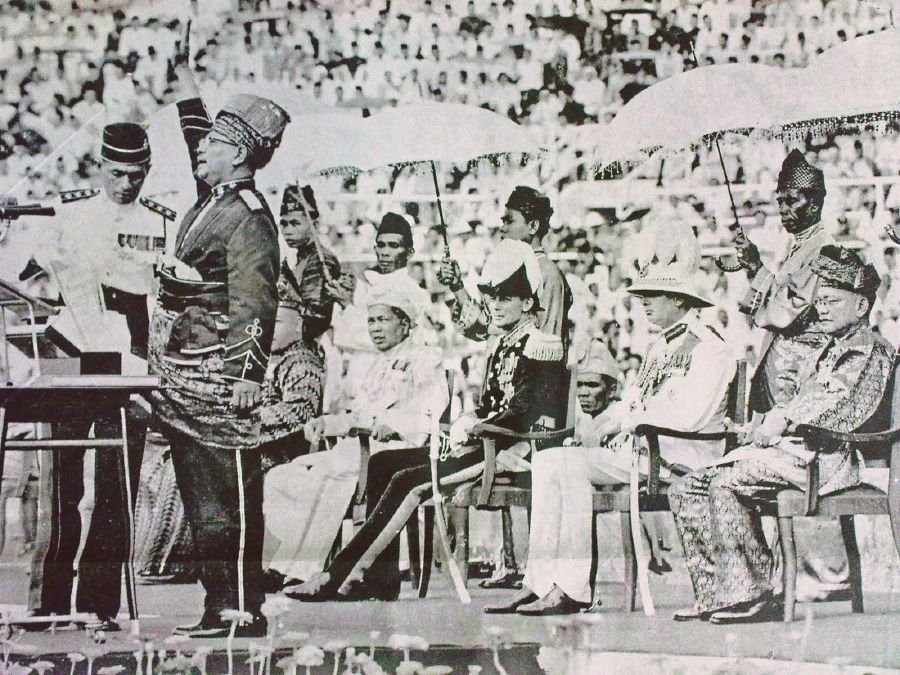

The 1952 Kuala Lumpur municipal elections presented a major challenge to the ideal of upholding a united front towards independence in Malaysia, as the political parties representing their respective ethnic groups ultimately won by forming a coalition rather than by uniting under the banner of a single multi-ethnic party (which is what UMNO’s previous leader, Datuk Onn Jaafar, had desired, in order to transform his party into one for all residents of Malaya). The UMNO and MCA ran on the same ticket, which MIC joined later; together, these parties of the Malayan, Chinese, and Indian communities formed the Alliance Party. In the first federal legislative council election, in 1955, the Alliance won 51 of 52 seats, placing itself at the forefront of transitional negotiations for full independence, which included establishing a commission for drafting the constitution.

Following the 1948 communist insurrection, the British were intent on ensuring that Malaya would be both a secure place for their business interests and a reliable bulwark against militant communist expansion.[28] In fact, the local and federal legislative council elections undermined much of the communists’ appeal. By 1952, a number of factors had combined to help the British sideline communist influences in Malaya: communist guerrilla tactics intended to force collaboration from rural residents had sparked resentment, British propaganda had influenced the population, relentless counterguerrilla warfare had pushed the communists deeper into the jungles, and the British had also resettled many “squatters” onto sultans’ crown land from rural areas where they had given the communists support.

During negotiations for interethnic citizenship in the mid-1950s, the British found themselves in the impossible position of acting as a mediator between the Chinese, the Malay and the Indians, and British business interests – all at a time when Britain was eager to rid itself of its colonial entanglements and focus on its Cold War and economic objectives.[29] UMNO’s leader, Tunku (Prince) Abdul Rahman (brother of the Sultan of Kedah, and therefore himself personally invested in the sultanates), pursued a two-pronged agenda of keeping the traditional sultanate states while unifying under a federal government and privileging Islam as the state religion.[30]

In 1956, an independent commission was formed to develop a constitution for an independent Malaya. Headed by Lord Reid, the commission included two jurists from India and Pakistan and two others from Britain and Australia. It received input from a range of Malayan stakeholders: the sultans and aristocracy, political parties, and religious groups, namely the Malay Christian Council and the Muslim Association of Malaya. [31]

Ultimately, the constitution established an electoral constitutional monarchy wherein the head of state is elected from among the nine rulers of the founding states of the federation. This constitutional monarch’s role is largely ceremonial. The parliament established by the constitution consists of two chambers: the Dewan Rakyat or lower house, which is directly elected and holds almost all powers concerning legislation, and the Dewan Negara or upper house, whose members are appointed by the legislative assemblies of each state. State legislative assemblies have parallel jurisdictions to the federal parliament, with similar parallel jurisdictions for criminal and civil Sharia laws and courts.[32] Finally, the constitution granted suffrage to all citizens of 21 years of age and up.[33]

Establishing a multiethnic federation as one nation-state wherein no ethno-religious group enjoyed a majority proved to be the sticking point for the Reid Commission. From the outset, Muslim groups, with strong pan-Islamic influences dating back to the late 19th century, demanded an establishment clause declaring Islam the official religion of the state. They also demanded that non-Muslims be refused citizenship unless they proved their loyalty to the new state across political, cultural, and educational spheres.[34] The sultans and aristocracy, as well as Christian leaders, opposed these demands. The former believed that Islam was already established as the official state religion in each state’s constitution, so an establishment clause in the federal constitution would infringe on their jurisdictions. The latter argued that even though no other religion enjoyed majority status in the country, neither did Islam, since Muslims made up less than fifty percent of the population.

In the end, it was upon the insistence of the Pakistani jurist that the establishment clause became the cornerstone of citizenship in the newly established state, declaring Islam to be the official state religion while also recognizing the freedom of non-Muslims to practice their faiths in peace.[35] The 1957 constitution also declared Malay to be the official state language, while allowing minorities freedom to teach and learn their languages. As such, it fulfilled the Alliance Party’s goals.

During the Malay Emergency, many laws had placed restrictions on freedom of speech and the press. They were now left intact and carried over to the post-1957 era. The constitution, as submitted by the Reid Commission and adopted by the Federation of Malay Parliament as part of the 1957 Independence Act, was extremely thin in terms of guaranteeing fundamental rights and liberties. It recognizes freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom from arbitrary arrest, but largely as theoretical principles; it does not allow courts any jurisdiction to review the constitutionality of laws that might infringe upon such freedoms.[36]

The Third Transition, 1957-63, and the Fulfillment of the “Grand Design,” Malaysia

On August 30, 1957, crowds gathered in Kuala Lumpur’s main square to celebrate Malaya’s official independence from Britain. The British flag was lowered and the new Malayan flag was raised as the crowd, led by Prince Tunku Abdul Rahman, chanted “Merdeka!” – “Independence!” The creation of Malaysia would drag on another six years as the British managed to convince the Tunku to consider negotiations with Brunei, North Brunei, Sarawak, and Singapore. With the exception of Brunei, all of these states joined the Malay Federation and formed the state of Malaysia upon British mediation in 1963.[37] However, fearing the ambitions of Singapore’s prime minister and the possibility of the Chinese population of Singapore and the Malay states forming a demographically greater and economically stronger component of Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman expelled Singapore from the federation by 1965.[38]

Despite the ups and downs of the establishment of Malaysia, British forces had by now managed to completely quell the communist insurgency, and the Malay Emergency was over. Now that Malaysia was established as a new state, the British “Grand Design” vision had been realized, with British economic interests preserved and communism sidelined. Malaysia was on its path to become an “Asian cub” that – unlike many of its newly independent counterparts in the Asian and African world – refrained from nationalizing industries, thus leaving Western business interests intact, and also maintained a capitalist economy that continues today.

Conclusion

Over the century leading up to the founding of the modern state of Malaysia in 1963, a broad range of competing interests and demographics posed a potential threat to national unity and independence. In the mid-19th century, European colonial powers dominated the region, with the British and Dutch competing for strategic trade routes and access to profitable natural resources. For their part, rather than directly resisting foreign encroachment, the Malay sultanates generally opted to negotiate the terms of their vassal status and seek participation in government wherever possible. Meanwhile, Malay elites tapped into anti-colonialist movements in their midst; again, rather than coming into conflict over diverging goals, they successfully leveraged those movements against the British and as a means of preserving their own legitimacy. Ultimately, the Malayan elites, through their active participation, managed to exercise agency in the shaping and re-shaping of the British “Grand Design,” effectively co-opting it to fit their vision, and consequently, giving “the Grand Design” a Malayan form and substance.

After World War II, it soon became clear that Malaya’s colonial status would come to an end one way or another – and the Alliance Party established the template for the path to independence and beyond, by forming a coalition of separate parties representing the Malay, Chinese, and Indian communities, rather than via a single multiethnic party. The Alliance Party transformed into the National Front in 1973, and between 1957 and 2018, it became the longest-ruling coalition party in the democratic world. The Alliance/National Front’s practices have sometimes fallen short of the intercommunal spirit it professes, and inter-ethnic conflict has erupted into violence, as in the “May 13, 1969 incident” of Sino-Malay post-election riots.

Nevertheless, the political model established prior to Malaysia’s independence offers an example of how a multiethnic society can transition into a stable federal constitutional monarchy. Likewise, the model of elites coopting popular movements rather than attempting to stamp them out demonstrates how a society organized around traditional monarchs can transition into a more democratic form of government without massive upheaval or civil strife. Despite a number of factors that could have stymied a peaceful democratic transition, from an elite power structure that could have resisted all change to a multiethnic demographic that could have clashed in civil war, Malaysia ultimately succeeded in traversing the road to a modern, independent, and democratic state that can offer a model for others seeking to follow the same path.

[1] Watson Andaya, Barbara, and Ishii, Youneo, “Religious Developments in Southeast Asia c. 1500-1800”, in Tarling, Nicholas ed. The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press, 1993. 508-567. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521355056.

[2] Andaya, Leonard Y., “Interactions with the Outside World and Adaptations in the Southeast Asian Society, 1500-1800”, in Tarling, Nicholas ed. The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press, 1993. 345-395 https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521355056.

[3] Trocki, Carl A. “Political Structures in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries.” In The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, 2:79–130. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521355063.003.

[4] Hirschman, Charles. “The Making of Race in Colonial Malaya: Political Economy and Racial Ideology.” Sociological Forum 1, no. 2 (1986): 330-61. https://faculty.washington.edu/charles/new%20PUBS/A51.pdf.

[5] Fauzi Abdul Hamid, Ahmad. “Malay Anti-Colonialism in British Malaya: A Re-Appraisal of Independence Fighters of Peninsular Malaysia.” Journal of Asian and African Studies (Leiden) 42, no. 5 (2007): 371–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909607081115.

[6] Smith, Simon C. “‘Moving a Little with the Tide’: Malay Monarchy and the Development of Modern Malay Nationalism.” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 34, no. 1 (2006): 123–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/03086530500412165.

[7] Stilt, Kristen. “Contextualizing Constitutional Islam: The Malayan Experience.” International Journal of Constitutional Law 13, no. 2 (2015): 407–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mov031.

[8] Slight, John, “British Colonial Knowledge and the Hajj in the Age of Empire”, Ryad, Umar, The Hajj and Europe in the Age of Empire, Leiden: Brill, 2017.

[9] Azizuddin Mohd Sani, Mohd. “Free Speech in Malaysia: From Feudal and Colonial Periods to the Present.” Round Table (London) 100, no. 416 (2011): 531–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2011.609694.

[10] Noh, Abdillah. “Malay Nationalism: A Historical Institutional Explanation.” Journal of Policy History 26, no. 2 (2014): 246–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030614000050.

[11] Kratoska, Paul, and Ben Batson. “Nationalism and Modernist Reform.” In The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, 2:249–324. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521355063.006.

[13] Hutchinson, Francis E. “Malaysia’s Independence Leaders and the Legacies of State Formation Under British Rule.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 25, no. 1 (2015): 123–51. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1356186314000406. Also see Rusenko, Rayna M. “Imperatives of Care and Control in the Regulation of Homelessness in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: 1880s to Present.” Urban Studies (Edinburgh, Scotland) 55, no. 10 (2018): 2123–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017710121.

[14] Lees, Lynn Hollen. “Urban Civil Society: The Context of Empire.” Historical Research: the Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research 84, no. 223 (2011): 135–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2281.2009.00537.x.

[15] Fook-Seng, Philip Loh. “Malay Precedence and the Federal Formula in the Federated Malays States, 1909 to 1939.” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 45, no. 2 (222) (1972): 29-50. Accessed August 16, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41492059.

[16] Trocki, Carl A. “Political Structures in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries.” In The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, 2:79–130. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521355063.003.

[17] Hutchinson, “Malaysia’s Independence Leaders and the Legacies of State Formation Under British Rule.” 129-134.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Noh, Abdillah. “Malay Nationalism: A Historical Institutional Explanation”. 246-73.

[20] Stockwell, A. J. “MERDEKA! Looking back at Independence in Malaya, 31 August 1957.” Indonesia and the Malay World 36, no. 106 (2008): 327–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639810802450308.

[21] Belogurova, Anna. “The Chinese International of Nationalities: The Chinese Communist Party, the Comintern, and the Foundation of the Malayan National Communist Party, 1923–1939.” Journal of Global History 9, no. 3 (2014): 447–70. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740022814000205.

[22] Azmi Arifin. “Local Historians and the Historiography of Malay Nationalism, 1945-57: The British, The United Malays National Organization (UMNO) and the Malay Left.” Kajian Malaysia: Journal of Malaysian Studies 32, no. 1 (2014): 1-35.

[23] Azizuddin Mohd Sani, 533-537.

[24] Smith, 130-133.

[25] Amoroso, Donna J. “Dangerous Politics and the Malay Nationalist Movement, 1945–47.” South East Asia Research 6, no. 3 (1998): 253–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967828X9800600303.

[26] Hutchinson, 145.

[27] Harding, Andrew. The Constitution of Malaysia: a contextual analysis. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2012. 25.

[28] Stockwell, A.J. “Malaysia: The Making of a Grand Design.” Asian Affairs (London) 34, no. 3 (2003): 227–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/0306837032000136279.

[29] See White, Nicholas J. “British Business Groups and the Early Years of Malayan/Malaysian Independence, 1957-65.” Asia Pacific Business Review 7, no. 2 (2000): 155–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/713999080. and Stockwell, A.J. “Malaysia: The Making of a Grand Design.”

[30] Harding, Andrew. The Constitution of Malaysia. 25.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.85-111.

[33] Ibid. 161-192.

[34] Stilt, “Contextualizing constitutional Islam”, 410-420.

[36] Harding, Andrew. The Constitution of Malaysia. 2-5.

[37] Stockwell, A.J. “Malaysia: The Making of a Grand Design.” 232-233.

[38]Cheong, Yong Mun. “The Political Structures of the Independent States.” In The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, 2:387–466. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521355063.008. 409-415.