Vision and Motivation

“They are not alive or dead. They are disappeared.” [1]

– Jorge Videla, former Argentine military dictator

“We’ve come to find your daughter, she’s a subversive,” the soldiers screamed before blasting the door with grenades, ransacking the house and threatening terrified parents.[2] “If we don’t find her,” they warned ominously, “you won’t find her either.”[3] Graciela Mellibovsky, a 29-year-old student activist was snatched from the street on an ordinary Autumn afternoon, months after Jorge Videla’s military government seized power in 1976.[4]

And she was not alone. Thousands of students, journalists, and lawyers vanished without trace during the seven-year reign of terror dubbed Argentina’s Dirty War. Many were not even politically active, but in this paranoid political climate merely appearing in an activist’s address book could warrant abduction.[5] “I think Gustavo’s only crimes were those of being young, of thinking and dissenting,” explained Elena De Pasak following the abduction of her 19-year old son.[6]

les Times. 11 May, 2011

“It was a Sunday, the day after the abduction,” Graciela’s mother, Mathilde recalled, “[My husband and I] went into the street like two zombies…we were like two souls walking, abandoned…”[7] Neighbours denied hearing the previous night’s commotion; their lawyer was too frightened to hand over the writ of habeas corpus and a friend advised seeing a fortune teller.[8] Newspaper headlines cryptically announced “Armed Confrontations” and “Subversives Shot,” but gave no further details. Endlessly traipsing ministries and morgues in search of further information proved fruitless.[9]

One evening Mathilde noticed a short Spanish editorial in the Buenos Aires Herald describing a gathering at Buenos’ Aires Plaza de Mayo. “It didn’t explain their purpose, but this was during a time when we were under siege,” recalling, “I felt it had something to do with me.”[10] Curious, she took the bus to the square and discovered the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo.

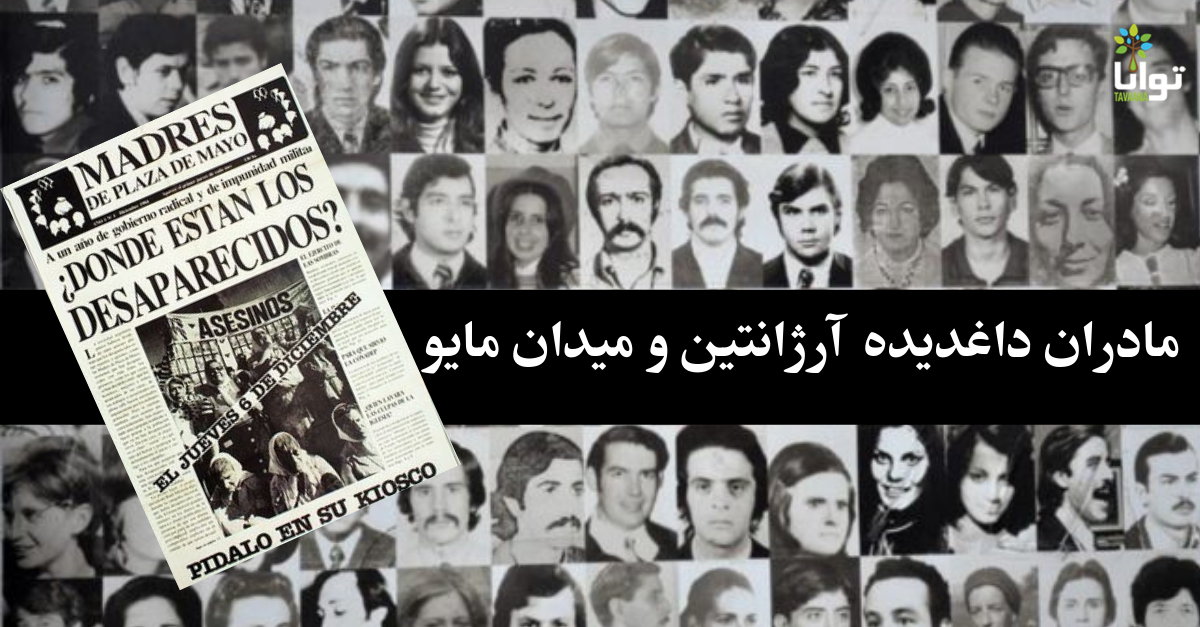

United by the disappearance of their children, fourteen Mothers defied the military’s ban on public gatherings and met in Plaza de Mayo on April 30, 1977. Forgetting the 30th was a Saturday, they arrived to find the square deserted. “It was just us and pigeons,” one mother remembered.[11] Undeterred, they returned again and again, at first they huddled around the benches pretending to knit, but soon grew bolder, piling up the belongings of their disappeared children to attract public attention.[12] The police objected and demanded the Mothers “move along;” they promptly complied, and the marching began.[13] “When [my son] disappeared my first reaction was to rush out desperately to look for him…nothing else mattered..,” one mother explained. “Then I realised that we had to look for all of them and that we had to be together because together we were stronger.”[14]

Goals and Objectives

“…We mothers are not begging for an answer, we are demanding it in the name of justice at its most basic, because it is our right.”

– Mothers’ letter to politician Ricardo Balbin, 1980

“Where are our children?” the mothers demanded ceaselessly, “We want the truth.” Yet the government feigned ignorance, with the Minister of the Interior, General Harguindeguy, suggesting their sons had run away and their daughters had become prostitutes.[15] The Mothers retaliated with public protests, marching every Thursday around the center of the Plaza de Mayo.[16] “By coming out and showing the photographs and seeing people’s reactions,” explained one mother, ”we were showing our countrymen the dreadful truth that the dictatorship took pains to hide in thousands of ways.”[17]

Unwillingly thrust into the limelight by the disappearances, the Mothers were initially not politically motivated. Most were housewives, and few were educated beyond high school.[18] “I didn’t know many things, I wasn’t interested. The economic, the political situation of my country were totally foreign to me, indifferent,” Hebe de Bonafini remembers.[19] When they officially registered as the Association of the Mother of the Plaza de Mayo in 1979, they proclaimed their principle to “avoid influence from political or sectional factors.”[20] The mother’s were not fighting for political gain, but simply to learn the fate of their children and hold those responsible for the disappearances accountable:“We started out of terror, impotence, emptiness, paralysis from fog and shadow,” recounts one mother, “[but] under each kerchief you’ll find stubbornness, tenacity, courage and a demand for truth and life.”[21]

Leadership

“We’re wasting time,” Azucena Villaflor chided restlessly, “We have to go to the Plaza de Mayo- meet there, then…we’ll get into the Government House because we’re not going to let anyone stop us and we’re going to talk to Videla.”[22] Determined, charismatic, and decisive, 52-year old Villaflor welcomed the Mothers to her own home, tirelessly petitioned international human rights organisations, and proposed wearing the iconic white scarves which symbolised their struggle.[23] “She was a born leader” recalls activist Nora de Cortinas fondly, “spontaneous, always with ideas, always helping.”[24]

Armed with little more than a grade school education and photos of her disappeared son, Villaflor refused to allow the regime to whitewash its international reputation. In spring 1977, just before one of the Mothers attempted to present a petition to US Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, she froze, petrified and unable to proceed. But, undeterred by the crowds or the soldiers, Villaflor grabbed the paper and thrust it personally into Vance’s hands. “That day, Azucena [Villaflor] showed me we were capable of doing things we could never have imagined,” she remembers. “We all knew that we were risking our lives, but there was no other way.”[25]

Flanked by uniformed police and watched by young men masquerading as passers-by,[26] the Mothers were well aware they were under surveillance.They arrived surreptitiously in small groups and devised simple codes to confuse phone tappers, but it wasn’t enough. On December 10, 1977, Villaflor disappeared on her way to buy “La Nacion” newspaper, which featured demands for justice and 834 mothers’ signatures. Betrayed by Alfredo Astiz, a handsome young intelligence officer posing as the distraught brother of a disappeared student,[27] Villaflor and four others were abducted, drugged and thrown from a plane into the Río de la Plata.[28] “They thought by kidnapping her…they would destroy our movement,” explained one of the Mothers. “They didn’t realise this would only strengthen our determination.”[29]

By 1983, however, the crumbling of the military dictatorship triggered political fault lines within the group. As the new democratically-elected government, led by President Raúl Alfonsín, revealed the enormity of the previous regime’s crimes and convicted a small number of junta officials, the mothers increasingly demanded justice rather than answers, but disagreed on how to best achieve this.

Under the leadership of Hebe de Bonfini, who had been chosen as the Association’s president a few years earlier, many mothers became increasingly defiant.[30] Bonafini’s uncompromising political stances and her perceived authoritarianism ultimately provoked a group of Mothers to split from the Association to form the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo Founding Line in 1986.[31] Both groups remained profoundly committed to vindicating and preserving their children’s memories, but whereas the Founding Line was willing to negotiate with the government, the Association rejected any kind of compromise.[32] “We find ourselves separated from our sisters,” one mother explained, “but we never confront each other; we all persevere in our firm decision not to give up.”[33]

Civic Environment

“First we will kill all the subversives; then we will kill their collaborators, then…their sympathisers, then those who remain indifferent; and finally the timid.”

– General Iberico Saint Jean, Governor of Buenos Aires, May 1976[34]

How did Argentina arrive in such a violent place? It began with a coup on March 25, 1976. Shortly after midnight, President Isabel Martinez de Peron boarded a helicopter to return to her suburban home, but never arrived.[35] As tanks rolled through Buenos Aires, she was flown to the city’s airport and taken into “protective custody.” Following an impromptu inauguration ceremony, General Videla and his military junta seized power, proclaimed martial law, and vowed to “restore the essential values of the nation.”[36]

Just three decades earlier, under the presidency of Isabel de Peron’s charismatic husband, Argentina enacted popular economic reforms, leading to increased wages, bank nationalization, and reduced working hours.[37] However this boom was short-lived; soon the economy stagnated, then slumped dramatically. In 1975 prices jumped 335% as inflation soared.[38] As the government floundered, violence escalated with right-wing paramilitaries and Communist guerrillas battling for supremacy in the country’s streets. Kidnappings, bombings, and assassinations were commonplace as the country teetered on the brink of civil war.

Exhausted by chaos and uncertainty, many welcomed the junta and their National Reorganisation Process. “Now we are governed by gentlemen” famed Argentine author Jorge Borges announced jubilantly.[39] This optimism quickly waned as political parties were dissolved, unions disbanded, and police were stationed in university classrooms.[40] Committed to eliminating “left-wing subversion” and prepared to use ”severe force to completely eradicate the vices that affect the country,” the military regime unleashed the terror which was to characterise Argentina’s Dirty War.

Convinced that “Argentinian society would never have tolerated firing squads”[41] and anxious to avoid the international backlash sparked by Chile’s military coup, Videla resorted to more insidious methods to silence his opponents. Anyone arbitrarily labelled “subversive” was dragged from the streets and tortured in secret detention centres. “A terrorist is not just someone with a gun or bomb,” Videla declared, “but also someone who spreads ideas that are contrary to Western and Christian civilization.”

Fear and disbelief paralysed dissent. “People were scared,” remembers Taty Alameda whose son disappeared in 1975. “If I talked about him at the hairdresser or supermarket, people would run away. Even listening was dangerous.”[42] In this atmosphere of terror, censorship, and misinformation, Argentine civil society did not oppose what was happening and many believed that the people seized were guilty.

Within this environment of extreme repression, the mothers had a unique level of freedom to demand justice and answers. Motherhood is revered in religious and secular communities across Latin America and this reverence opened a small window of opportunity for Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo.[43] The military was lulled into a false sense of security by these apparently non-threatening Mothers.[44] By the time the military realized their mistake, it was too late

Message and Audience

“We were supposed to keep our mouths shut: we made accusations

We were supposed to be submissive: we unmasked them

We were supposed to be quiet: we screamed with all our might

Above all, we were supposed to stay at home, but we went out, walked around, walked into unimagined places.”[45]

– Circle of Love over Death: Testimonies of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo

As euphoric crowds poured onto Buenos Aires’ streets following Argentina’s defeat of Holland in the 1978 World Cup final, even the military regime momentarily abandoned its strict curfews. Yet minutes away from the confetti and celebrations, thousands of dissidents were being tortured in the infamous Navy-Petty School for Mechanics.[46] While the stadium’s ground staff painted black armbands on the goalpost to mourn the disappeared,[47] the Mothers capitalised on the international media frenzy. “It’s easy,” one of them said. All they had to do was look at the journalist and say “We want our children back. We want them to tell us where they are.”[48]

What started as a silent protest by fourteen apprehensive mothers in an empty square evolved into an human rights campaign of international proportions. One mother handed Pope John Paul II a petition during a trip to Mexico and hundreds traveled the world sharing their stories. Shocked by their testimonies, a group of Dutch activists promptly abandoned plans to investigate conditions in the Soviet Union and instead focused on Argentina.[49]

Back in the Plaza, the Mothers held huge photographs of their children, organised flash protests and held 24 hour vigils. The cloth nappies the Mothers donned in the early days changed too, becoming the iconic white scarves embroidered with their childrens’ names.[50]

In Autumn 1983, artists memorialized the disappeared by adorning the Plaza with thousands of life-size faceless silhouettes. Student volunteers unfurled long rolls of paper and painted dark outlines of men, women, and children in thick black paint, before gluing them to the walls. “When I first saw those silhouettes, I remembered the dolls that I used to make for my disappeared daughter,” recalled one mother, “[these] silhouettes… mixed with my remembrances… and conjured up the mystery of those kids who were missing, but for a moment regained life and even seemed to come back just to be with us.”[51]

The Mothers also covered the Plaza with a million paper hands. “I remember the slogan – from the start it made me enthusiastic,” one mother recalled. The slogan, “during the year of the young, lend a hand,” inspired women from 66-countries to oblige, sending drawings of their own hands accompanied by their names.[52] Through this international outreach, the mothers attracted the attention of foreign governments including the United States, which cut off military aid to Argentina in 1977.[53] Others, like Sweden, outraged at the disappearance of their own citizens in Argentina, became strong supporters of the Mothers.[54]

Although branded “mad women” and ridiculed by the junta, support for the Mothers swelled. Over a thousand participated in the March of Resistance in December 1982[55] and a year later almost thirty thousand gathered to support the Mothers as the military government imploded amid the Falklands fiasco.[56] “At long last, the ominous era of ‘process’ was coming to an end,” and “we really believed that all of us without any exception were going to receive news about our children,” recalls one mother sadly, “but this was not to be.”[57]

The 1983 democratically-elected government did not pursue the vigorous prosecution of the war criminals that they had hoped for. Faced with a choice between unlimited pursuit of justice or sustaining the fragile democratic transition, successive governments were disposed to close the books on the past and reconcile with the still powerful military.[58] “The Statute of Limitations and Law of Due Obedience were passed in quick succession, minimising both the definition of human rights criminals and the time period in which they could be accused. [The government] investigated a lot concerning the disappeared,” complained one mother, “but it revealed very little about the disappearers.”[59]

In a vain attempt to placate the Mothers, while eluding criminal responsibility, the government publicly opened the mass graves, broadcasting endless macabre images of bulldozers raking through bones. However, the Mothers demands for justice never faltered. “No to the final conclusion, no to impunity,” they demanded. “Trial and punishment for all guilty parties.” [60]

Although the marches continued, slowly the marchers divided. Accepting the death of their children, the Founding Line favored cooperation, compensation, and preserving the memory of their children.[61] The Association Mothers, however, disagree. ”How can you put a price on your child’s life without acknowledging why they were killed,” Bonafini argued.[62] For them, honoring the memory of their children translated into the adoption of their political ideals and supporting causes they believe their children would have endorsed. The result has been an association with leftist, sometimes violent, revolutionary rhetoric, which has been met with dismay. Many have condemned these developments, including the Founding Line, which has maintained a commitment to peaceful means.[63]

Conclusion

“They are a living myth. The mothers were not Batman and Robin. They were ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. . . And they brought down a military government.” [64]

– Luis Moreno Ocampo, International Criminal Court Prosecutor

The mothers continue to march today, despite many being in their late 80’s. “We know that because of our age we will probably not live to see every single culprit condemned,” admits Taty Almeida. “But though we may need our canes and walking sticks, for the time being the Mad Mothers are still around.”[65] Their determination and persistence has been rewarded by the repeal of the Statute of Limitations and Law of Obedience, the trials of more than a thousand war criminals, and Videla himself spending the end of his life in prison.[66]

Most importantly, the Mothers have inspired a culture of fighting injustice – a legacy that will surely outlive them. In 2017, Argentine courts moved to release an imprisoned former police investigator and war criminal. The outraged mothers were joined in the plaza by tens of thousands of citizens waving white scarves until the law was amended, preventing the planned release.[67] Many Mothers never found their children, but their example helped a society to find its voice in the face of injustice and never let the horrors of the past be forgotten.

Learn More

News and Analysis:

- D’Alessandro, Andres & Kraul, Chris. “Argentina learns a lesson: You don’t cross the Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza.” Los Angeles Times. 11 May 2011. http://www.latimes.com/world/mexico-americas/la-fg-argentina-human-rights-20170511-story.html

- Goñi, Uki. “40 years later, the mothers of Argentina’s ‘disappeared’ refuse to be silent.” The Guardian. 28 Apr. 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/28/mothers-plaza-de-mayo-argentina-anniversary

- Kurtz, Lester. “The Mother of the Disappeared: Challenging the Junta in Argentina (1977-1983).” International Center on Nonviolent Conflict. July 2010. https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/the-mothers-of-the-disappeared-challenging-the-junta-in-argentina-1977-1983/

- “Madres de Plaza de Mayo.” International Institute of Social History. https://socialhistory.org/en/collections/madres-de-plaza-de-mayo

- “The mother of all scandals?” The Economist. 16 June 2011. https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2011/06/16/the-mother-of-all-scandals

- “Nunca Más (Never Again).” Conadep (National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons) 1984. http://www.desaparecidos.org/nuncamas/web/english/library/nevagain/nevagain_001.htm

- Perfil Staff. “La Línea Fundadora, las “Otras” Madres.” Perfil. 24 Mar. 2011. http://www.perfil.com/noticias/contenidos/2011/03/22/noticia_0042.phtml

- Perelman, Marcia & Torras, Veronica. “The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo: ‘We were born on the march.”OpenDemocracy. 3 Oct. 2017. https://www.opendemocracy.net/protest/mothers-plaza-de-mayo

- Prieto, Martin. “Síntomas de división entre las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo.” El País. 8 Feb. 1986. https://elpais.com/diario/1986/02/08/internacional/508201218_850215.html

Books

- Amnesty International. Disappearances: A Workbook. New York: Amnesty International USA, 1981.

- Arrogsagary, Enrique. Biografía de Azucena Villaflor. Creadora del Movimiento de Mardes de Plaza de Mayo. Buenos Aires: Cienflores, 2014.

- Bonner, Michel D. Sustaining Human Rights: Women and Argentine Human Rights Organizations. University Park, PA: Penn State Press, 2010.

- Bousquet, Jean Pierre. Las Locas de la Plaza de Mayo. Buenos Aires: El Cid, 1982.

- Bouvard, Marguerite Guzman. Revolutionizing Motherhood: The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. Wilmington, De: Scholarly Resources Inc., 1994.

- Steiner, Patricia Owen. Hebe’s Story: The Inspiring Rise and Dismaying Evolution of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. United States: Xlibris, 2003

Videos

- TV Pública Argentina. “Madres de la Plaza de Mayo. La historia.” Playlist. Youtube. Mar. 2015. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLxaulh35hPBvNm3yDkzcueBHMHPbxFVkZ

- The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. Directed by Susana Blaustein Muñoz & Lourdes Portillo, 1985.

- The Official Story. Directed by Luis Puenzo, Historias Cinematograficas Cinemania, Progress Communications, 185.

Footnotes:

[1] Webber, Jude. “Former Argentine Military Dictator Jorge Videla Dies in Jail.” Financial Times, 17 May 2017.

[2] Mellibovsky, Matilde, et al. Circle of Love over Death: Testimonies of the Mothers of the Plaza De Mayo. Curbstone Press, 1997. p. 227

[3] Ibid. p.229

[4] Ibid.

[5] Lusher, Adam. “The Argentine Mother Who Took on the Junta Dictatorship over Her ‘Disappeared’ Son.” The Independent, 5 Nov. 2017, The Argentine mother who took on the Junta dictatorship over her ‘disappeared’ son.

[6] Mellibovsky p.218

[7] Mellibovsky p.228

[8] Ibid. p.230

[9] Mellibovsky

[10] Ibid. p.234

[11] Perelman, Marcia & Torras, Veronica. “The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo: “We were born on the march”.” openDemocracy. 3 Oct. 2017 https://www.opendemocracy.net/protest/mothers-plaza-de-mayo

[12] Tedla, Aden. “1977-83: Mothers of Plaza De Mayo Protest Disappearances in Argentina.” Libcom.org, 20 June 2011.

[13] Perelman, Marcia & Torras, Veronica

[14] McFarland, Sam. “Azucena Villaflor, the Mothers of the Plaza De Mayo, and Struggle to End Disappearances.” International Journal of Leadership and Change, vol. 6, no.1, 6 Jan. 2018.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ocampo, Luis Moreno. “Beyond Punishment: Justice in the Wake of Massive Crimes in Argentina. Journal of International Affairs Vol. 52, No.2 (spring, 1999).

[17] Mellibovsky. p.228

[18] Bouvard, Marguerite Guzman. Revolutionizing Motherhood: The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources Inc., 1994. p.1

[19] “Hebe De Bonafini, Latin America’s Most Famous Mother.” TeleSUR, 14 May 2017.

[20] Perfil Staff. “La Línea Fundadora, las “Otras” Madres.” Perfil. 24 Mar. 2011 http://www.perfil.com/noticias/contenidos/2011/03/22/noticia_0042.phtml.

[21] Mellibovsky

[22] Mellibovsky

[23] Bouvard pp.68-69

[24] McDonnell, Patrick. “Argentines Remember a Mother Who Joined the ‘Disappeared.’” LA Times, 24 Mar. 2006.

[25] McFarland

[26] Mellibovsky p.179

[27] Trigona, Marie. “Argentina’s Mothers of Plaza De Mayo: A Living Legacy of Hope and Human Rights.” ZNET, 28 Oct. 2010.

[28] McDonnell, Patrick

[29] McFarland

[31] Prieto, Martin. “Síntomas de división entre las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo.” El País. 8 Feb. 1986 https://elpais.com/diario/1986/02/08/internacional/508201218_850215.html.

[32] Goddard, Victoria Anna. “Demonstrating resistance: Politics and participation in the Marches of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo.” Focaal No. 50 (2007).; Steiner, Patricia Owen. Hebe’s Story: The Inspiring Rise and Dismaying Evolution of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. United States: Xlibris, 2003. pp.199-200

[33] Mellibovsky p.179

[34] Streitfeld, David. “Haunted by the Past.” The Washington Post, 5 Mar. 1995.

[35] “Argentine Junta Under army chief assumes control.” New York Times, 25 Mar. 1976.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Minster, Christopher. “Biography of Juan Peron.” ThoughtCo, 8 Apr. 2018.

[38] “Argentine Junta Under army chief assumes control.” New York Times, 25 Mar. 1976.

[39] Hollingshead-Cook, Keith. Ideology Vs.Practice in Argentina ‘s Dirty War Repression. University of Tennessee Honors Thesis, 2006.

[40] Mellibovsky

[41] Gunson, Phil. “ Jorge Rafaél Videla Obituary.” The Guardian, 17 May 2013.

[42] Goñi , Uki. “Blaming the Victims: Dictatorship Denialism Is on the Rise in Argentina.” The Guardian, 29 Aug. 2016.

[43] Malin, Andrea. “Mother Who Won’t Disappear.” Human Rights Quarterly Vol. 16, No. 1 (Feb., 1994). 187-188

[44] Ibid p. 203

[45] Mellibovsk

[46] Hersey, Will. “Remembering Argentina 1978: The Dirtiest World Cup of All Time.” Esquire, 14 Aug. 2018.

[47] Forrest, David. “The Political Message Hidden on the Goalposts at the 1978 World Cup.” The Guardian, 5 July 2017.

[48] Goddard, Victoria Anna. “Demonstrating resistance: Politics and participation in the Marches of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo.” Focaal No. 50 (2007); Steiner, Patricia Owen. Hebe’s Story: The Inspiring Rise and Dismaying Evolution of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. United States: Xlibris, 2003. p.100

[49] Mellibovsky p.124

[50] Mellibovsky

[51] Ibid.

[52] Mellibovsky p.172

[53] Malin p.209

[54] Bouvard pp.83-84

[55] Ibid p.128

[56] Ibid p.172

[57] Ibid p.133

[58] Ocampo

[59] Mellibovsky p.166

[60] Mellibovsky

[61] Goddard

[62] Cala, Andres. “The Argentine Mothers Who Defied a Regime.” OZY, 31 May 2015.

[63] Steiner p.192

[64] McDonnell

[65] Goñi , Uki. “ 40 Years Later, the Mothers of Argentina’s ‘Disappeared’ Refuse to Be Silent.” The Guardian, 28 Apr. 2017.

[66] Caistor, Nicholas. “General Jorge Rafael Videla: Dictator Who Brought Terror to Argentina in the ‘Dirty War’.” The Independent, 17 May 2013.

[67] D’Alessandro, Andres & Kraul, Chris. “Argentina learns a lesson: You don’t cross the Mothers and Grandmothers of the Plaza.” Los Angeles Times. 11 May, 2011. http://www.latimes.com/world/mexico-americas/la-fg-argentina-human-rights-20170511-story.html