Vision and Motivation

The Mafia has long been a dominant force in Italy.[1] According to the anti-Mafia office of the Italian retailers’ association, the Mafia extorts 200 million euros a day from Italian businesses.[2] The challenge of organized crime is particularly acute on the island of Sicily. While there are law enforcement bodies dedicated to fighting organized crime, for most Sicilians, according to the head of Italy’s anti-racket commission Tano Grasso, “It is more convenient for them to pay up than to report them.”[3]

The Mafia has long been a dominant force in Italy.[1] According to the anti-Mafia office of the Italian retailers’ association, the Mafia extorts 200 million euros a day from Italian businesses.[2] The challenge of organized crime is particularly acute on the island of Sicily. While there are law enforcement bodies dedicated to fighting organized crime, for most Sicilians, according to the head of Italy’s anti-racket commission Tano Grasso, “It is more convenient for them to pay up than to report them.”[3]

The Mafia’s requirement to pay the Pizzo, or protection money, has been a burden on most Sicilians because financial success only leads to larger monetary demands from organized crime rings. Yet by the end of the 20th century, Sicilians began to challenge the status quo and reclaim their freedom. According to Pasquale Masucci, a computer technician, “For too long ordinary citizens of Palermo and business people have been held ransom, and now we are fighting back.”[4]

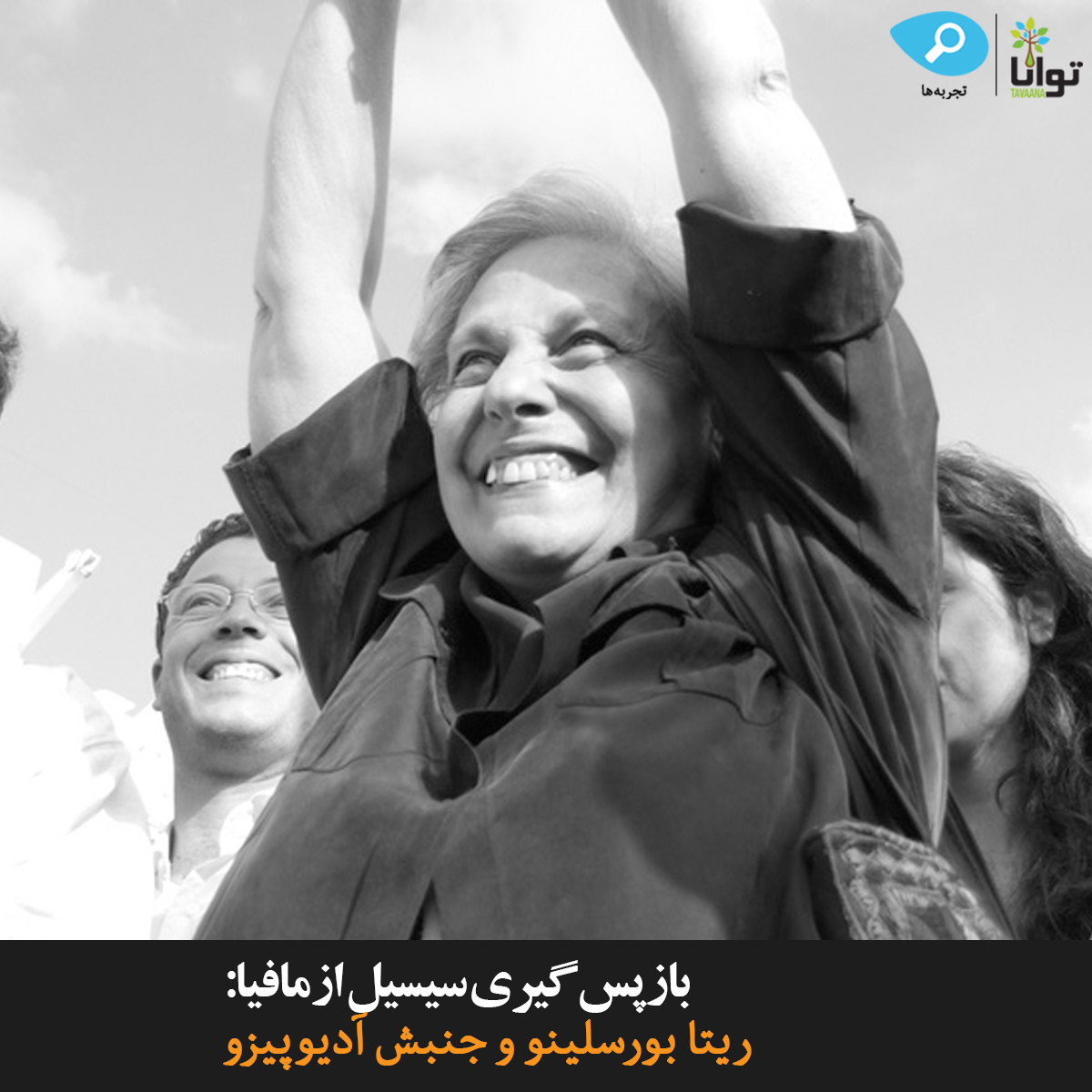

For Rita Borsellino, a leading anti-Mafia activist, the path to civic leadership began in 1992 after her brother, Judge Paolo Borsellino, was killed in a car bombing orchestrated by the Sicilian Mafia. His murder forced Rita to take action.[5] Though Rita was nearly fifty and had been living in Mafia-dominated Palermo her entire life, her personal tragedy sparked the outrage that led to the creation of the anti-Mafia movement, LIBERA, meaning “free.” Her example demonstrates that it is never too late to take up a cause to improve society.

Likewise, the Addiopizzo organization, which means “goodbye to protection payments,” is an important civic movement pushing to break the financial chains of bondage that were put in place by Sicily’s Mafia. Addiopizzo was founded by a few young restaurateurs in 2004, as a by-product of a generation that witnessed the killings of anti-Mafia activists, judges, journalists and businesspeople. Addiopizzo‘s vision was simple: a Sicily where the Mafia did not control all sectors of the economy and where businesses of all sizes could keep 100% of their profits.[6]

Goals and Objectives

Borsellino sought to put an end to the Mafia’s intimidating and crippling Pizzo by establishing LIBERA, an association of small organizations working to combat the Mafia, in 1995. Through LIBERA, Borsellino educated the Italian people about a nonviolent and peaceful system of economics, one with respect for the rule of law and human rights, a system that had been lost in the world of organized crime.[7] More than helping jumpstart businesses that did not pay the Pizzo, LIBERA began building farms out of land confiscated by the government in order to grow Mafia-free agricultural products, Libera Terra, to be sold in Pizzo-free establishments.[8]

Addiopizzo similarly challenged the mafia by empowering business owners to refuse the Mafia’s demands by creating a strong support network. Addiopizzo worked with business owners to open and run Pizzo-free businesses to show the Sicilian people that there is a viable alternative to the Mafia-dominated business culture. Addiopizzo used the example of Libero Grassi, a business owner who stood up to the Mafia in 1991 by refusing to pay the Pizzo. Grassi tried to organize a group of supporters, but no one was willing to stand up to the Mafia as he had; Grassi was murdered that same year. At Addiopizzo rallies, speakers have declared, “There is no better time to say no. You will not be left alone. These are no longer the 1990s, when Libero Grassi was murdered, because he was abandoned.”[9]

Leadership

Too often movements are sparked by injustices, and like so many others, Borsellino’s catalyst for becoming a civic leader was driven by personal tragedy. In her work at LIBERA, she has managed to unite numerous societal groups to heed her call for a Mafia-free economy.[10] In this manner, Borsellino expanded the organization to include over 1,500 associations that successfully combat the Mafia’s influence in the Sicilian market. Her accomplishments led her to electoral politics; Borsellino was elected as an Italian Member to the European Parliament in 2009 to address the Mafia’s negative economic influence on a transnational level.

Too often movements are sparked by injustices, and like so many others, Borsellino’s catalyst for becoming a civic leader was driven by personal tragedy. In her work at LIBERA, she has managed to unite numerous societal groups to heed her call for a Mafia-free economy.[10] In this manner, Borsellino expanded the organization to include over 1,500 associations that successfully combat the Mafia’s influence in the Sicilian market. Her accomplishments led her to electoral politics; Borsellino was elected as an Italian Member to the European Parliament in 2009 to address the Mafia’s negative economic influence on a transnational level.

Addiopizzo was founded by young entrepreneurs who, when budgeting to open a restaurant, decided they did not want to pay the Pizzo. One morning, Palermo woke up to Addiopizzo‘s message plastered all over the city: “A whole people who pay the Pizzo is a people without dignity.”[11] Addiopizzo founders recall, “initially we didn’t think we’d succeed so well. We simply wanted to open the debate.”[12] Addiopizzo is unique in that it has no formal leadership structure, seeking to achieve results rather than fame. In 2006, it was believed that there were about 50 people running the organization who worked with hundreds of cooperating businesses.[13]

Without an official spokesperson or visible leader, individual members seek to further the movement by taking initiative and leading by example – Fabio Messino, for example, saw the need for a Pizzo-free supermarket and invested his life savings in the venture that became known as the Punto Pizzofree.[14] Hundreds of businesses like Messino’s have popped up all over Palermo; they offer a popular, ethical alternative to the businesses that still pay the Pizzo and have also become a popular destination for ethical tourism.[15]

Civic Environment

In an effort to maintain their influence and hold on power, the Mafia developed a culture of fear in Sicily through intimidation and violence. The government, on a local, regional and national level, did little to support those who stood up to the Mafia. Even as Addiopizzo grew in strength, its political links were negligible. Messina notes, “We haven’t received any political backing, and in any case, I never expected we would get that.”[16] In general, Italy’s political leaders have shied away from dealing with the Mafia. Marco Travaaglio, a critic of the current Berlusconi government, explained, “It was thought that whoever talks about fighting the Mafia, scares a certain segment of the electorate…In reality, if you don’t talk about the Mafia, it is because you want Mafia votes.”[17]

However, in recent years there has been a shift in government behavior and the overall civic environment following the arrests of a number of significant Mafia figures, including the 2006 capture of Bernardo Provenzano, head of the Sicilian Mafia, known in most circles as the “boss of all bosses”. On the first day of Provenzano’s trial, more than 100 shopkeepers signed their names and shops onto an online petition that refused to participate in the Mafia’s protection racket.[18] Many politicians are now more willing to speak out against the Mafia, and those who were complicit in the Mafia’s corruption, kidnappings and killings are being put on trial. Angelino Alfano, a member of President Berlusconi’s People of Freedom Alliance, explains that the changes in governmental Mafia-acquiescence, combined with the civic actions of anti-Mafia movements like LIBERA and Addiopizzo, are ending an era of fear: “A lot of companies have decided to trust the state and believe the state will protect them.”[19]

Message and Audience

Addiopizzo‘s grassroots movement was founded to connect businesses and consumers opposed to the Pizzo in order to establish a community of support against the Mafia’s dominance of the Sicilian economy. At the core of Addiopizzo‘s message was a simple yet powerful desire to improve the standard of living of Sicilians. Their message, “A whole people who pay the Pizzo is a people without dignity,”[20] was described by Addiopizzo founders as “a call to arms, a way to get attention.”[21] It was often displayed on stickers throughout the city to generate shame for those who paid the Pizzo. As an emblem of the organization, members used a broken circle with an ‘X’ in the middle with the phrase “Consumo Critico,” or “Critical Consumption”, so that non-Pizzo products and businesses are recognizable to all.

Addiopizzo‘s grassroots movement was founded to connect businesses and consumers opposed to the Pizzo in order to establish a community of support against the Mafia’s dominance of the Sicilian economy. At the core of Addiopizzo‘s message was a simple yet powerful desire to improve the standard of living of Sicilians. Their message, “A whole people who pay the Pizzo is a people without dignity,”[20] was described by Addiopizzo founders as “a call to arms, a way to get attention.”[21] It was often displayed on stickers throughout the city to generate shame for those who paid the Pizzo. As an emblem of the organization, members used a broken circle with an ‘X’ in the middle with the phrase “Consumo Critico,” or “Critical Consumption”, so that non-Pizzo products and businesses are recognizable to all.

Success stories like Messina’s Punto Pizzofree supermarket stand as a proud symbol of the anti-Mafia movement, allowing ordinary people to stand against crime families through daily actions like buying groceries. “Customers like the fact that, in this shop, they can actually make a statement each time they buy a product,” Messina notes.[22] It was the simplicity, yet boldness, of this action that appealed to the residents of Palermo. According to one customer, “If everybody does just one thing like this then we are all making a stand against the Mafia.”[23] Humor has also become a vehicle for disseminating the anti-Mafia message; Messina sells hats in his store that symbolizes a new era. “This used to be the type of cap often worn by Mafiosi; they’d wear it straight, like this. But the company is called La Coppola Storta (Jaunty Cap) because we wear it differently, at an angle. It’s about reclaiming and re-interpreting a symbol, giving it a positive meaning.”[24]

Borsellino uses education as her means to disseminate her anti-Mafia messages, hoping to reach all Italians, because, according to her, “The fight against the Mafia must touch all of Italy.”[25] By 1999, LIBERA had trained and educated more than 8,000 teachers and 800,000 students, including many young Italians still in primary school. A volunteer with the organization, Silvia Pellegrino, argued, “If we are educating people now about how to defy the Mafia but fail to teach those younger than us, we will never be able to reach our goal of eliminating the Mafia.”[26] To reach that goal, LIBERA organizes class speakers and field trips to educate Sicilian youth, including some children whose parents belong to the Mafia. According to Borsellino, “The children can become the messengers of positive [values] inside their own family.”[27]

Outreach Activities

Both Addiopizzo and LIBERA have established coalitions of like-minded organizations to further their cause. As Messina notes, “All you need to do is introduce consumers to producers, neither of whom want to pay the Pizzo, [to] bring about a common bond, more ethical consumption and a client loyalty which is absolutely guaranteed.”[28] By 2008, Addiopizzo‘s network had expanded to include 204 businesses and over 9,000 local Italians who have officially registered with the organization.

Both Addiopizzo and LIBERA have established coalitions of like-minded organizations to further their cause. As Messina notes, “All you need to do is introduce consumers to producers, neither of whom want to pay the Pizzo, [to] bring about a common bond, more ethical consumption and a client loyalty which is absolutely guaranteed.”[28] By 2008, Addiopizzo‘s network had expanded to include 204 businesses and over 9,000 local Italians who have officially registered with the organization.

LIBERA sought to connect diverse groups and organizations in Italy with the common goal of combating the power and influence of the Mafia. Its reach, however, extends beyond the struggle against the Mafia and includes cultural, sporting and volunteer associations, who seek out Borsellino’s education programs and training seminars.[29] With Italy moving in the right direction, Borsellino is now focused on expanding her coalition internationally, while Addiopizzo continues to register more Pizzo-free business throughout the country, giving Italians and global citizens alike the hope that one day Italy can completely rid itself of the Mafia.

Learn More

News & Analysis

“Addiopizzo.” Wikipedia. 22 August 2010.

Holmes, Stephanie. “Rita Borsellino: Anti-Mafia Camaigner.” BBC News. 14 April 2008.

Holmes, Stephanie. “Sicilians Grow Defiant of Mafia.” BBC News. 11 April 2008.

Johnston, Vanessa. “Anti-Mafia Products Make Their Mark in Sicily.” Deutsche Welle. 11 May 2010.

Kington, Tom. “Shopkeepers Revolt Against Sicilian Mafia.” The Observer. 9 March 2008.

Moore, Malcolm. “Italy’s Biggest Business: The Mafia.” The Telegraph. 23 October 2007.

Moore, Malcolm. “We Won’t Pay You Protection, Traders Tell Mafia.” The Telegraph. 28 April 2006.

Pisa, Nick. “Mafia-free Supermarket Defies Mob Extortion.” The Telegraph. 8 March 2008.

Round, Andy. “Mafia Free Holiday – An Offer You Can’t Refuse?” Sabotage Times. 24 August 2010.

Rossant, John. “A Bullet for a Businessman.” Business Week. 4 November 1991.

“One Hundred Defiant Shopkeepers Say ‘We Don’t Pay Protection Money.'” Corriere. 3 May 2006.

“Rita Borsellino, the anti-Mafia Candidate.” L’Humanite, 11 April 2008.

“To the Mafia’s Horror, Pizzo-Free Shop Opens Palermo Doors.” Agence France Presse. 8 March 2008.

Books

Jamieson, Alison. The Antimafia: Italy’s Fight Against Organized Crime. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000.

Orlando, Leoluca. Fighting the Mafia and Renewing Sicilian Culture. New York: Encounter Books, 2003. Second Edition.

Multimedia

“Sicilian Girl.” Dir. Marco Amenta. Perf. Veronica D’Agostino. Pid, 2009. DVD.

“Italy: Taking on the Mafia.” Frontline. January 27, 2009.

“TEDxPalermo – Dario Riccobono – Addiopizzo Against Mafia.” YouTube. August 16, 2010.

Footnotes

[1] Moore, Malcolm. “Italy’s Biggest Business: The Mafia.” The Telegraph. 23 October 2007.

[2] “Protesting the ‘Pizzo’: Anti-Mafia Market to Tour Italy.” Spiegel Online. 27 March 2008.

[3] Moore.

[4] Pisa, Nick. “Mafia-free Supermarket Defies Mob Extortion.” The Telegraph. 8 March 2008.

[5] Holmes, Stephanie. “Rita Borsellino: Anti-Mafia Campaigner.”

[6] “One Hundred Defiant Shopkeepers Say ‘We Don’t Pay Protection Money.'” Corriere. 3 May 2006.

[7] Rita Borsellino.

[8] Johnston, Vanessa. “Anti-Mafia Products Make Their Mark in Sicily.” Deutsche Welle. May 11, 2010.

[9] “Italy: Taking on the Mafia.” Frontline. 27 January 2009.

[10] Borsellino.

[11] “Homepage.” Addiopizzo.org. 2010.

[12] “Italy: Taking on the Mafia.”

[13] Moore, Malcolm. “We Won’t Pay You Protection, Traders Tell Mafia.” The Telegraph. 28 April 2006.

[14] Pisa.

[15] Round, Andy. “Mafia Free Holiday – An Offer You Can’t Refuse?” Sabotage Times. 24 August 2010.

[16] “To the Mafia’s Horror, Pizzo-Free Shop Opens Palermo Doors.” Agence France Presse. 8 March 2008.

[17] Holmes. “Sicilians Grow Defiant of Mafia.”

[18] “One Hundred Defiant Shopkeepers Say ‘We Don’t Pay Protection Money.'”

[19] Ibid.

[20] “Homepage.” Addiopizzo.org. 2010.

[21] “Italy: Taking on the Mafia.”

[22] Ibid.

[23] Pisa.

[24] Holmes. “Sicilians Grow Defiant of Mafia.”

[25] “Rita Borsellino, the anti-Mafia Candidate.” L’Humanite, 11 April 2008.

[26] Greenleese, Nancy. “Young Sicilians take a brave stand against the Mafia.” Deutsche-Welle, 7 June 2010.

[27] Borsellino.

[28] “To the Mafia’s Horror, Pizzo-Free Shop Opens Palermo Doors.”

[29] Borsellino.