Vision and Motivation

Under President Hosni Mubarak, who ruled Egypt from 1981 until his overthrow in 2011, Egypt’s newspaper industry was dominated by the three government-run daily papers: Al Ahram, Al Akhbar, and Al Gomhuria.[1] Critics alleged that these newspapers served to celebrate the ruling regime, publish official government statements, and marginalize the political opposition.[2] Until 2004, the only other significant voices in the Egyptian press came from opposition party newspapers. However, many were known more for their lurid stories designed to increase sales, rather than for objective journalism or constructive dissent.[3]

In Egypt’s journalistic environment, the state-owned papers “had become the mouthpiece of the ruling party”, whereas opposition newspapers were only presenting their party’s views.[4] Although Egypt’s independent newspapers contained more freedom of opinion, they were published on a weekly basis, preventing them from timely news reporting.[5] While events like political protests went unreported in government papers, they were reported with a partisan spin in opposition papers, and hardly reported in a timely matter in the independent newspapers.

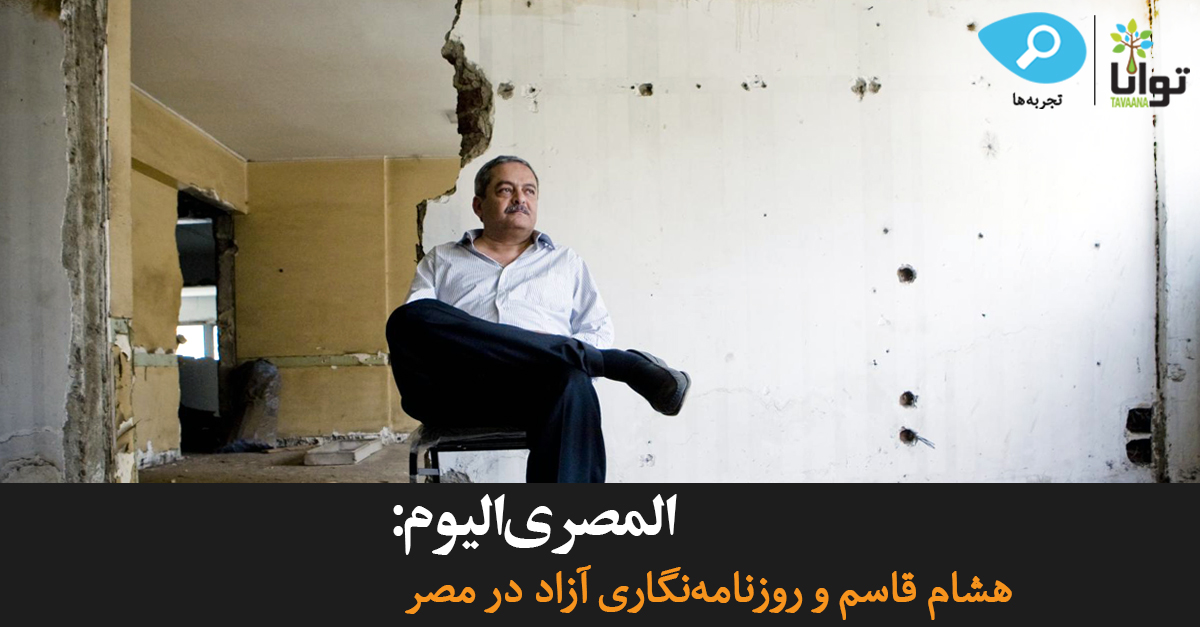

In 2003, a group of Cairene businessmen approached former Cairo Times editor Hisham Kassem with a proposal for founding an independent daily newspaper. Al Masry Al Youm (The Egyptian Today) was founded the following summer, with Kassem as its CEO.

Goals and Objectives

Kassem was initially skeptical of the idea behind Al Masry Al Youm, but he came to realize that it was an opportunity to break new ground in the Egyptian press. Kassem told his business partners, “What you need now is a paper of record in Egypt. That’s what’s missing.”[6]

Al Masry Al Youm‘s goal was to give Egyptian readers a newspaper free of political influence. The paper sought to provide reliable coverage on issues important to the Egyptian people, while providing multiple viewpoints on controversial topics. As El-Gallad puts it, Al Masry Al Youm “believes in the right of the reader to receive a great deal of objective and balanced information…thus leaving it up to the reader to take sides and form opinions.”[7]

In order to meet the interests of Egyptian citizens, Kassem clearly defined important topics to be covered in his newspaper: “civil liberties, human rights, political reform – that’s front-page material,” he stated. “And I want 80 percent of the news to be local.”[8]

Leadership

By launching Al Masry Al Youm, Kassem took the lead in creating a fresh approach to newspaper publishing in Egypt; he operated very carefully, however, knowing full well that starting a high-quality newspaper in a restrictive civic environment would be a difficult task. He compared it to “flying a 747 jetliner. It’s so big you have to move gradually.”[9]

As the CEO of Al Masry Al Youm, Kassem had to hire and manage a staff who would be fully dedicated to upholding the paper’s journalistic integrity. In order to do so, Kassem set strict criteria as he hired reporters, only looking for young university graduates who had not yet been influenced by the biases of mainstream Egyptian media. Keeping in mind his desire for an independent and unbiased newspaper, he ruled out hiring political and religious partisans.[10] Kassem hired Magdy El-Gallad as editor-in-chief after firing two problematic editors; the first refused to give contracts to women, while the second refused to run an alcohol ad on the grounds that it was haram.[11]

Throughout the long and arduous process of creating a quality newspaper, Kassem provided the necessary leadership and management skills to build a strong foundation for Al Masry Al Youm. In recognition of his work as “one of Egypt’s most prominent publishers and democracy activists,” the National Endowment for Democracy awarded Kassem their Democracy Award in 2007.[12]

Civic Environment

Under Mubarak, the Egyptian press enjoyed some freedom compared to most other Arab countries at the time, but it was still constrained by de facto limitations on content. The Ministry of Information monitored newspapers and exerted pressure on editors to avoid certain crossing certain “red lines”, such as publishing information on the military or the ruling Mubarak family.[13] As El-Gallad puts it, “There are attempts to influence us. Sometimes we receive threats, sometimes polite expressions of disappointment.”[14]

Due to government pressure, self-censorship became a common practice among Egyptian newspapers, including Al Masry Al Youm. In addition to the pressure it regularly applied to media outlets, the government exerted further influence through its control or printing presses and distribution networks, enabling it to remove newspapers from newsstands across the country.

Mubarak-era Egyptian penal code and press laws included 32 articles that allow for the imprisonment of journalists for such vague offenses as “threatening national security”.[15] This legislation enabled the government to crack down on journalists who crossed the aforementioned “red lines” that were imposed on the press. As Kassem explained: “We get new cases against us regularly. At some point almost every week, my assistant will hand me a new case. But we don’t get convicted.”[16] Despite government pressure on the Egyptian media, Kassem pointed out that “it [would have been] ultra-stupid for Mubarak not to leave a reasonable margin for the press.”[17]

Message & Audience

With a vision of offering the Egyptian people unbiased news, Kassem attempted to convey much the same message to his audience. While some activists use rallies, boycotts, and other direct means to spread their messages, Kassem did so with Al Masry Al Youm, proving the importance of press freedom by providing controversial and up-to-date coverage of sensitive political events happening in Egypt.

Perhaps the most significant example of this type of coverage was the paper’s reporting on Egypt’s 2005 elections. The elections came at a time when Egypt’s ruling National Democratic Party was trying to improve its international image by allowing candidates to run against President Hosni Mubarak in the presidential elections. However, when first-round parliamentary election results showed large gains for the Muslim Brotherhood, the regime responded with heavy interference in the next rounds of voting.[18] Many polling stations were closed or overwhelmed by violence from hired thugs and state security forces.

On November 24th, Al Masry Al Youm published a first-hand account of the election fraud on its front page. The story struck such a chord with Egyptians that it was republished for three straight days.[19] It exposed the truth behind the government’s electoral practices, prompting a national debate that inspired 120 judges to sign a statement attesting to the veracity of the allegations against the government.[20] Al Masry Al Youm had only been in existence for a little over a year during the reporting of the government scandal. Kassem states, “In January [of that year], our circulation was only 3,000. It was increasing steadily [by] about 500 copies a month, but after we ran this story, it jumped to 30,000.”[21]

Outreach Activities

Because Kassem’s newspaper was not specifically an activism movement, its outreach to others, and the goals of that outreach, are methodologically different from those of traditional activism movements. Al Masry Al Youm created a “mini-revolution” in the Egyptian press through its bold and independent news coverage, leading to a surge of new independent newspapers in Egypt.[22] With its 2005 election fraud reporting, the paper set a new standard for news coverage and analysis in Egypt, balancing its criticism of the regime with solidly researched investigative journalism.[23] Al Masry Al Youm inspired other independent journalists to report stories with a high caliber of objective reporting, and it had such a large impact on the Egyptian press that other media outlets were forced to cover stories that had been reported by Kassem’s paper.

In 2009, Al Masry Al Youm‘s circulation was 200,000, making it is the fourth-largest paper in the country; it had successfully expanded both its circulation and influence on other media outlets.[24] Kassem, who has moved on from Al Masry Al Youm to found a new newspaper, said that year that the government will not be able to close down the paper, because, he says quite simply, “We’ve now come too far.”[25] Egypt’s 2011 revolution, which overthrew the Mubarak government, also allowed Al Masry Al Youm to overtake the state-run press and become Egypt’s leading newspaper by a wide margin. According to the Dubai Press Club, the paper’s circulation doubled between 2008 and 2011, to the extent that Al Masry Al Youm commanded 61% of Egyptian newspaper readership in 2012.

Learn More

News and Analysis

Black, Jeffrey. “Egypt’s Press: More Free, Still Fettered.” Arab Media & Society 4, Winter 2006.

Diehl, Jackson. “The Freedom to Describe Dictatorship.” The Washington Post 27 Mar. 2006.

“Egypt 2009 Report.” Reporters Without Borders. 2010.

El-Jesri, Manal. “Pressing On.” Egypt Today 28:1 Jan. 2006.

“Home Page.” Al Masry Al Youm. 2010. (Arabic)

“Home Page.” Al Masry Al Youm English. 2010.

Salah-Ahmed, Amira. “Hisham Kassem profile.” Business Today May 2006.

Books

Muravchik, Joshua. The Next Founders: Voices of Democracy in the Middle East. New York: Encounter Books, 2009.

Wright, Robin B. Dreams and Shadows: The Future of the Middle East. New York: Penguin Press, 2008.

Video

“NED Award – Hisham Kassem.” National Endowment for Democracy. 8 Oct. 2007.

Footnotes

[1] Atia, Tarek. “The local scene: How Egyptians are getting their news in 2006.” Al-Ahram Weekly 799, 15-21 June 2006.

[2] “Egypt sacks newspaper old guard.” BBC News, 4 July 2005.

[3] Black, Jeffrey. “Egypt’s Press: More Free, Still Fettered.” Arab Media & Society 4, Winter 2006.

[4] El-Jesri, Manal. “Pressing On.” Egypt Today 28:1, Jan. 2006.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Allam, Hannah. “Egypt’s press has become surprisingly free – and lively.” The Mercury News, 23 Feb. 2006.

[7] El-Jesri.

[8] Allam.

[9] Wright.

[10] Allam.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “NED Honors Press Freedom Activists from Egypt, Russia, Thailand and Venezuela with 2007 Democracy Award.” National Endowment for Democracy, 2010.

[13] Cooper.

[14] El-Jesri.

[15] “Egypt 2009 Report.” Reporters Without Borders, 2010.

[16] Wright.

[17] Ibid.

[18] El-Amrani, Issandr. “Controlled Reform in Egypt: Neither Reformist Nor Controlled.” Middle East Report Online, 15 Dec 2005.

[19] El-Amrani.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Wright.

[22] Diehl, Jackson. “The Freedom to Describe Dictatorship.” The Washington Post, 27 Mar 2006.

[23] Salah-Ahmed, Amira. “Hisham Kassem profile.” Business Today, May 2006.

[24] Sandels, Alexandra. “Al Masry Al Youm English: New kid on the block in Egyptian Media.” Menassat, 1 Aug 2009.

[25] Ibid.