“The old Inquisition had its rack and its thumbscrews and its instruments of torture with iron teeth. We know what these things are today; the iron teeth are our necessities, the thumbscrews are the high-powered and swift machinery close to which we must work, and the rack is here in the firetrap structures that will destroy us the minute they catch on fire.”

– Rose Schneiderman, labour organiser and trade unionist, 1911[1]

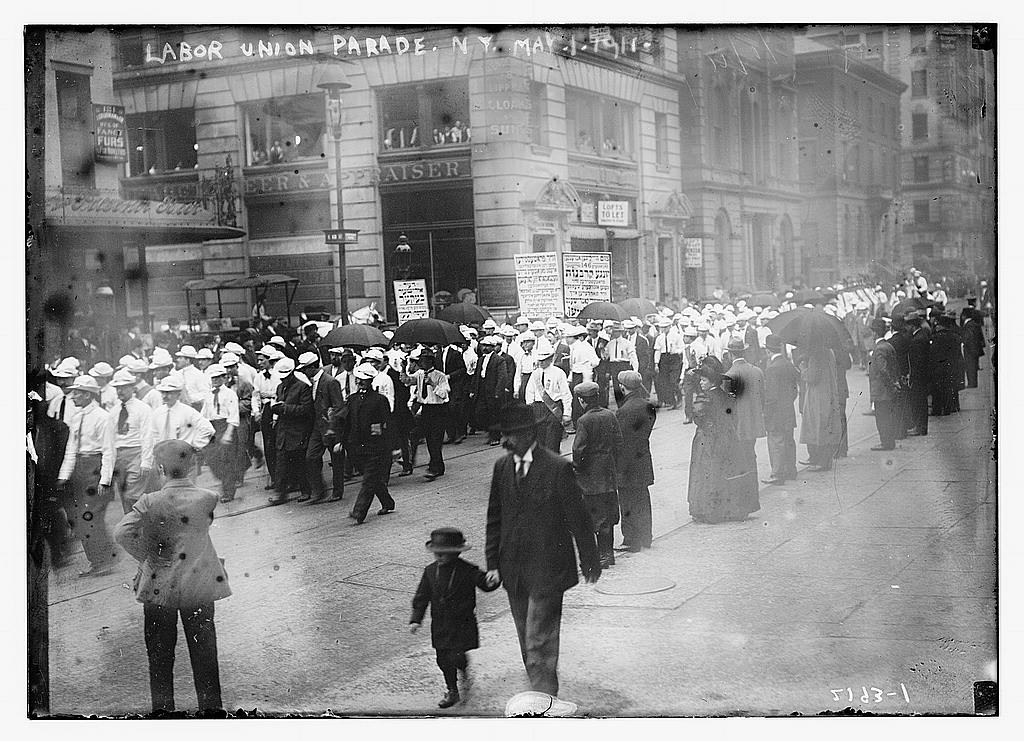

Labor union parade, NY., May 1, 1911 (Source: LOC)

Rising from the Ashes: Fighting for workers’ rights in New York slums

“DON’T JUMP, DON’T JUMP” the crowd screamed desperately. Nine floors up, she wavered, transfixed for a moment by the chaos and fear before leaping from the window; terrified, the other girls clung to each other and followed. Far below, their lifeless bodies smashed against the pavement, some still aflame. Just ten minutes before, they had collected their wages and excitedly planned their weekend when a small fire started under one of the sewing machines, sweeping through the piled up cloth. It devoured the cluttered work benches and soon the whole factory was ablaze. Escape was impossible: the stairs were chained shut to prevent unauthorised breaks and the elevators overloaded, “it was jump or be burned,” The Times reported, “fifty burned bodies were taken from the ninth floor alone.”[2]

Perched on the upper floors of the prestigious Asch building, Triangle Shirtwaist was just one of countless factories crammed into Manhattan’s booming garment district. Every day, hundreds of young idealistic Jewish girls fleeing Russia’s pogroms arrived on New York’s docks, to be subsumed by the industry or commandeered for prostitution.[3] Squeezed in front of sewing machines, inches apart, they worked 12 hour days for $4 a week, and were charged extra for electricity, broken needles and even chairs at an exorbitant profit.[4] Business was cutthroat, and workers fungible; should one dare refuse, a hundred more would clamour to take her place.

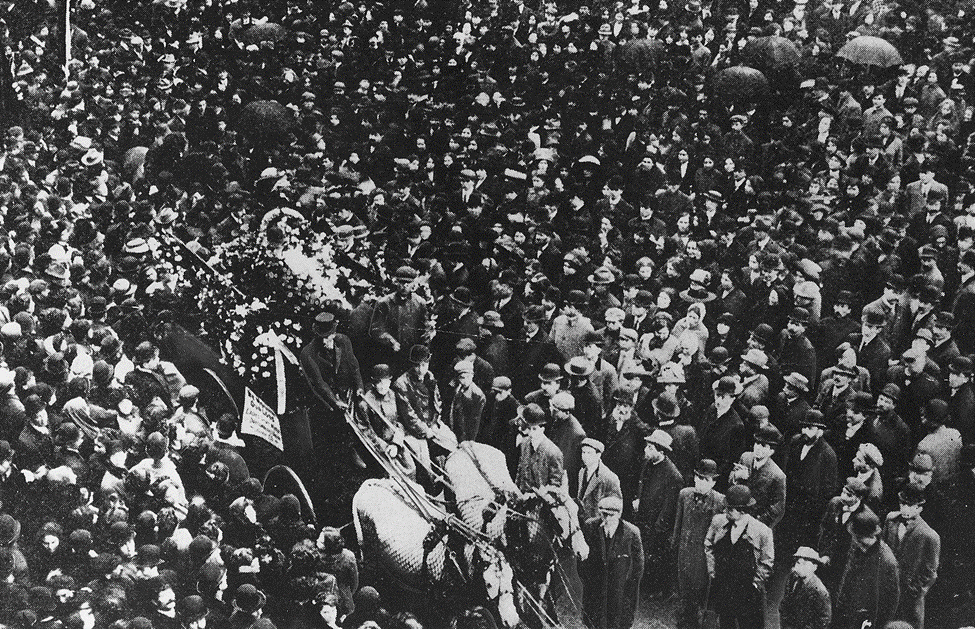

Standing in front of the blackened factory, stunned New Yorkers watched silently as wagonfulls of coffins arrived for the 136 charred bodies; over 200,000 gathered to pay their last respects.[5] Factory managers and public officials squabbled, issuing apologies designed not to express regret, but deflect blame, with the press profiteering from the outrage. Ultimately, the courts exonerated the factory’s owners from criminal charges, demanding only 23 payments of $75 to compensate the families.[6] This proved that existing safety legislation was not only ineffective, but unenforced. Just four inspectors were charged with policing home work across New York, who struggled partly as “the conditions were so bad that they themselves hated to penetrate the foul atmosphere.”[7] While some prayed for the fire’s victims, others vowed reform or revenge. “I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came to talk good fellowship…” Rose Scneiderman passionately addressed the audience at the Metropolitan Opera House, “…Too much blood has been spilled … it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.”[8]

The Battle of the Ideologies: Pity vs. Empowerment

“If every working man and woman would join a trade union then the wages would be sufficient to support people and then the families would be able to look after themselves and there would not be this necessity for these various services that go on through the charity societies…”

– Trade union activist and founder of Chicago Commons[9]

Hundreds of mourners gather around a funeral procession for victims of the Triangle fire (CC BY 2.0)

United as strangers in a foreign land, newly arrived immigrants in the 1880’s banded together to pool resources, pay for medical treatment and support vulnerable families.[10] With the right contacts and a few rolls of fabric, some budding entrepreneurs started their own enterprises.[11] Community ties cemented these functional relationships; factory floors became makeshift synagogues, as Jewish workers swept aside their sewing machines to pray.[12] Gradually these self-help groups coalesced into unions and their solidarity was powerful, with wildcat strikes able to paralyse the garment industry; but there was a darker side too.

Volatile industrial relations resembled “guerrilla warfare.” with “pacts between opposing parties treated as passing pieces of paper to be torn up when tempers went into a tantrum.”[13] Strikes often turned violent, with union-defying strikebreakers punished harshly. Not only were they assaulted and blacklisted, but hounded and ostracised by their own communities, sometimes driving them to suicide.[14] Divisions ran deep, not only between different nationalities but within them; some Italians voluntarily segregated their streets by region.[15] Union membership itself was erratic, swelling one day as hundreds of thousands united to strike, but evaporating the next.[16]

Realizing that success required not transient fragmented interest groups, but a “national union to aid its struggles … against the atrocities of mean and oppressing employers,” trade union delegates formed the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) on June 3, 1900.[17] At first it floundered, but gradually gained momentum as 20,000 strikers united to demand a 52-hour week in 1909. After the “Great Cloakmakers Revolt” the following year, union ranks swelled to 75,000.[18] The unprecedented 1910 Protocol of Peace attempted to exchange anger for arbitration, by increasing minimum wages, demanding holiday pay and establishing bipartisan boards to deal with grievances and safety.[19]

Just months after these agreements were signed, the Triangle factory burned, convincing citizens it was imperative to “devise preventative methods, and insist on them being carried out.”[20] However, New York’s stratified society disagreed on the best way to achieve this. Poverty, many in the middle classes believed, was self-inflicted or precipitated by intemperance, while trade unions were communist leaning “unladylike” affairs, and best avoided. The legislature agreed; strikes remained illegal under federal law until 1932, with strikers often fired en masse, issued with injunctions or consigned to the workhouse.[21] When the Red Cross distributed donations to grieving families, payments were deliberately meagre lest they “interfere with the work ethic or promote dependence.”[22]

Unsurprisingly, the workers disagreed. Tired of endless empty promises and belated pity, they campaigned for unionisation and collective bargaining rights. Arbitrarily amending a few laws or doling out money would alter nothing; instead the system needed an overhaul; by the workers, for the workers. Working in deplorable conditions for little pay, the rebels had increasingly little to lose. “We are starving while we work” shouted charismatic Clara Lemlich rallying her fellow strikers, “we might as well starve while we strike.”[23]

Frances Perkins; From factory Floor to Secretary of Labour

“Every man and woman who works at a living wage, under safe conditions, for reasonable hours, or who is protected by unemployment insurance or social security, is [Frances Perkins’] debtor.”

– Former Secretary of Labour, Willard Wirtz[24]

Unassuming, but firm and determined, it was Frances Perkins who ultimately helped break this ideological deadlock by bridging the disparate worlds of the socialists and socialites. Watching helplessly as the Triangle factory burned, she vowed to make a difference. Initially she was destined for an “a life of genteel good works”, but the fire changed everything; “what had been a career turned into a vocation, [and] moral indignation set her on a different course.”[25]

Impatient with the “[genteel progressives’] prissiness, their desire to stay pure and above the fray…”, Perkins hardened as, “she threw herself into the rough and tumble of politics.”[26]

From confronting corrupt Democratic “bosses” in the notorious Hell’s Kitchen slums[27] to dissipating potentially explosive miners’ strikes,[28] Perkins navigated this murky political world. As executive secretary of the New York Consumer’s League she vividly documented “tubercular children coughing into bread dough” in the city’s bakeries and non-existant fire precautions,[29] attracting the attention of powerful allies including future President Roosevelt. Rewarded for her diligence, she ascended swiftly through the ranks, rising from Industrial Commissioner to Secretary of Labor in 1933.[30]

Despite her lofty position as America’s first female cabinet minister, Perkins never sought personal power. Amidst rumours of her potential appointment, she handed a candid letter to Roosevelt, “I honestly hope that what they have been printing about me is…incorrect”, she wrote, “for your own sake and that of the U.S.A.…”. The President’s response was equally direct, “Have considered your advice”, he replied shortly, “ and don’t agree.”[31] Stepping into his office, Perkins clearly outlined her demands for minimum wages, maximum hours, unemployment insurance and pensions. “Are you sure you want this done?”, she warned one last time, “because you won’t want me for Secretary of Labour if you don’t.”[32] He agreed and she achieved it.

Legislation, Perkins believed, was critical to true reform. Unscrupulous employers could always pack up shop and flee South to evade even the most zealous of unions. Passing federal laws, however, was a challenging task. Not only did many contemporary economists consider meddling with free markets tantamount to sacrilege, but unconstitutional and an encroachment on states’ jurisdiction.[33] Perkins’ first attempt to secure employees’ rights to organise trade unions, increase wages and eliminate child labour through the National Industrial Recovery Act 1934 (NRA) was shot down by the Supreme Court.[34] However, ingenious exploitation of the tax law ensured its key principles were resurrected in the National Labour Relations Act (1935) and Fair Labour Standards Act (1938).[35]

Moving these laws beyond the statute books and onto the factory floor required the unions. Together with consumer and industry representatives, unions hammered out the details of 500 Industrial codes, regulating everything from the Cotton to the Poultry trades.[36] When workers complained that employers were evading minimum wage provisions by not providing time clocks, the unions stepped in, developing a form for accurately calculating hours worked and promptly distributed 250,000 copies of it. [37]

What are you going to do about it? Enlisting the support of the masses

“When Labor strikes it says to its master I shall no longer work at your command. When it votes for a party of its own, it says: I shall no longer vote at your command. When it creates its own college and classes, it says: I shall no longer think at your command. Labor’s challenge to Education is the most fundamental of the three.”

– Henri Deman, French Socialist [38]

Selling the virtues of trade unionism to a government crippled by the depression was challenging and even convincing the workers themselves proved difficult. Creative communication was essential. With workers from across the globe, messages could easily get lost in translation: the Local 22 Dressmaker’s Union alone boasted 32 nationalities.[39] Written in the English-Yiddish street slang, the Forward newspaper combined trade unionist ideology with compelling problem pages, advising readers on the best way to track down runaway husbands or gain citizenship.[40] The Italians sang to unite, “No more the drudge and idler, ten that toil that one reposes,” they chanted as they marched, “But the sharing of life’s glories”.[41] The light-hearted musical “Pins and Needles” with a cast of sewing machine operators, was an instant Broadway hit and even performed at the White House.[42]

Pragmatic policymakers however preferred statistical research to music. Perkins complied, not only supplying figures on accident rates and malnutrition, but commissioning her own research. For instance, she discovered aluminum dust could spontaneously combust, so she adopted codes to eliminate it.[43] Data, however, needed to be complemented by empathy. Perkins believed the best way to convince sceptics was simply to show them. She invited influential democrats to see exhausted rope workers after a 12-hour shift, children as young as five working in a canning factory, and to squeeze through a tiny “fire escape” ending with a rickety iron ladder 12 feet above the ground. “[New York governor] Alfred Smith said it was the greatest education he’d ever had,” Perkins recalled proudly, “He’d grown up in the slums of New York, but he did not know what factory life was like.”[44]

Beyond Compensation and Safety: Workers’ rights in the time of the Depression

“…The specter of unemployment – of starvation, of hunger, of the wandering boys, of the broken homes, of the families separated while somebody went out to look for work – stalked everywhere. The unpaid rent, the eviction notices, the furniture and bedding on the sidewalk, the old lady weeping over it, the children crying…”

– Frances Perkins, Speech to Social Security Headquarters, 1962[45]

Throughout the 1920’s America’s economy boomed, with manufacturers competing to satisfy the market’s vociferous appetite for everything from flapper dresses to Ford T cars. Reformers chased behind, attempting to plug loopholes in fire safety and overtime legislation as quickly as devious employers could out-manoeuvre them. Unexpectedly growth slowed, with activists initially welcoming the lull to focus on the more insidious dangers of factory work, including silicosis and tuberculosis[46]; but soon it became clear something was terribly wrong. On October 24th, 1929, the stock market crashed, plunging millions of Americans’ savings into oblivion.

Overnight, work became a scarce resource to be rationed: unions were no longer fighting for wages but jobs, and legislators needed to change tack. Industries reduced hours and introduced work sharing to curb redundancies while the Federal Emergency Relief Act 1933 provided the unemployed with food, rent and fuel allowances.[47] Combining his passion for conservation with employment creation, Roosevelt engaged almost 3 million unskilled men in planting trees and constructing dams through the Civilian Conservation Corps. [48]

Perkins however, set her sights even higher, considering the depression not a disaster but an opportunity. “Nothing else would have bumped the American people into social security.” she explained, “except something so shocking, so terrifying, as the Depression”. [49] Her demands were clear and uncompromising; she wanted unemployment insurance, pensions, disability insurance and she wanted it now. Leading the Committee on Economic Security to draft legislation she “placed a large bottle of Scotch on the table, and told them no one would leave until the work was done.”[50] When President Roosevelt attempted to procrastinate amid Conservative criticisms, Perkins “hit the roof,” overruled his objections and ensured the landmark Social Security Act was passed in 1935.[51]

Manhattan – Dhaka – Beijing: The Globalised Garment Industry

“I didn’t jump to save my life…I jumped to save my body, because if I stayed inside the factory I would burn to ash, and my family wouldn’t be able to identify my body.”

– Sumi Abedin, survivor of Tazreen factory fire, 2012[52]

Workers’ rights evolved swiftly over the subsequent decades in the United States. Women were guaranteed equal wages[53], racial discrimination in the workplace was outlawed[54] and the Occupational Health and Safety Act (1970) was enacted. However, stockbrokers slowly replaced domestic seamstresses as globalization pushed supply chains further afield, out of the city’s cramped lofts to factories worldwide.[55] Today, Bangladeshi teenagers embroider US-designed dresses destined for the London high-street, and the same problems remain. In 2012, 112 died as Tazreen Fashions on the outskirts of Dhaka burned to the ground.[56] A year later Bangladesh was reeling from yet another “mass industrial homicide” as Rana Plaza collapsed killing more than 1,100. [57]

The details were chillingly reminiscent of Triangle; workers were trapped behind padlocked doors and barred windows.[58] Safety reports had been filed and ignored.[59] Appalled consumers, shocked by graphic photos of their favourite designer labels amid charred bodies, boycotted the brands, convinced that if people did not buy clothes made in sweatshops, “the evil would be stopped.”[60] Yet this strategy was flawed; boycotts would cut jobs, removing the “only viable work option”[61] from 4 million women, forcing them into insalubrious “informal” work, and be “suicide for [the] country.”[62]

The new legislation, industrial codes and additional audits were mooted too, but critics were skeptical. Deplorable conditions were already illegal in most countries, but the laws remained unenforced. Nike for example, showed glowing paperwork audits, but deeper analysis revealed 80% of factories either hadn’t improved or had worsened.[63] Auditing is a “cat and mouse game” in some Chinese factories, a song played over the loudspeaker alerts workers of inspectors’ arrival prompting children to flee to the back.[64]

Like Perkins, activists realised true reform could not be imposed by well meaning legislation or conscience-stricken consumers alone, but required collaboration from the unions. The 2013 amendments to Bangladesh’s Labour Act boosted trade union rights while global brands and international unions signed the Building and Safety Accord, a legally binding agreement regulating safety and independent inspections.[65] Covering thousands of factories and millions of workers, the Accord’s track record is encouraging; 85% of safety hazards identified by initial inspection across 2000 factories have been rectified.[66] “…There are parents walking around not dead because of [the Accord],” explains labour rights supporter Catherine Albisa, “there are kids who are not orphans because of this.”[67]

Learn More

News and Analysis

- Kew, Michelle. “Frances Perkins: Private Faith, Public Policy.” Frances Perkins Center, www.francesperkinscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Frances-Perkins-Private-Faith-Public-Policy-by-Michelle-Kew.pdf.

- “Her life: The woman behind the new deal.” Frances Perkins Center http://francesperkinscenter.org/life-new/.

- Dreier, Peter. “If You Like Social Security and Minimum Wage, Thank Frances Perkins.” HuffPost, 6 Dec. 2017. www.huffpost.com/entry/if-you-like-social-security-and-minimum-wage_b_7475098.

- Hobbes, Michael. “The Myth of the Ethical Shopper.” The Huffington Post, 2015, http://highline.huffingtonpost.com/articles/en/the-myth-of-the-ethical-shopper/

- Stillman, Sarah. “Death Traps: the Bangladesh Garment Factory Disaster.” The New Yorker, 1 May 2013. www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/death-traps-the-bangladesh-garment-factory-disaster.

- Seibel, Brendal. “How NYC Tenements Once Hid Secret Sweatshops.” Timeline, 20 June 2018 www.timeline.com/how-nyc-tenements-once-hid-secret-sweatshops-c38cd350ba46.

- Morris, David. “When Unions Are Strong, Americans Enjoy the Fruits of Their Labor.” HuffPost, 4 Aug. 2011. www.huffpost.com/entry/when-unions-are-strong-am_b_846802

- Franklin, Cory. “ Out of the Ashes of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire.” The Guardian, 6 Mar. 2011. www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/cifamerica/2011/mar/06/us-unions-usa.

Books

- Pasachoff, Naomi. Frances Perkins: Champion of the New Deal. Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Guglielmo, Jennifer. Living the Revolution: Italian Women’s Resistance and Radicalism in New York City 1880-1945. University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Tyler, Gus. Look for the Union Label: A History of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. Routledge, 1995.

- Soyer, Daniel. A Coat of Many Colors: Immigration, Globalization, and Reform in New York City’s Garment Industry. Fordham University Press, 2004.

Multimedia

- “The Woman Behind the New Deal; The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR’s Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience” Democracy Now https://www.democracynow.org/2009/3/31/the_woman_behind_the_new_deal

- “Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire.” Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cT8fah14WDs

- “The decline of labour unions in the US: Fault lines.” Al Jazeera English, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zpWhy5krLXk

Footnotes

[1] Stein, Leon. Out of the Sweatshop: The Struggle for Industrial Democracy. Quadrangle/New Times Book Company, 1977, pp.196-197.

[2] Greenwald, Richard E. “The Burning Building at 23 Washington Place’: The Triangle Fire, Workers and Reformers in Progressive Era New York.” New York History, vol. 83, no. 1, 2002, pp.55–91.

[3] Pasachoff, Naomi. Frances Perkins: Champion of the New Deal. Oxford University Press, 2000. p.19

[4] Tyler, Gus. Look for the Union Label: A History of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union. Routledge, 1995. p.53

[5] Greenwald, pp.55–91.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Soyer. p.37

[8] Stein. p.18

[9] Pasachoff. p.18

[10] Tyler .p.53

[11] Soyer. p.94

[12] Ibid. p.127

[13] Tyler. p.35

[14] Soyer. p.132

[15] Luconi, Stefano. “Forging an Ethnic Identity: The Case of Italian Americans.” Revue Française d’Études Américaines, 2003, pp. 89–101. www.cairn.info/revue-francaise-d-etudes-americaines-2003-2-page-89.htm.

[16] Tyler. p.35

[17] Tyler. p.43

[18] “Protocol of Peace.” Encyclopedia.com, 2014, www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/protocol-peace.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Pasachoff. p.29

[21] Morris, David. “When Unions Are Strong, Americans Enjoy the Fruits of Their Labor.” HuffPost, 4 Aug. 2011, www.huffpost.com/entry/when-unions-are-strong-am_b_846802.

[22] Greenwald, Richard E. “The Burning Building at 23 Washington Place’: The Triangle Fire, Workers and Reformers in Progressive Era New York.” New York History, vol. 83, no.1, 2002, pp. 55–91.

[23] “Excerpt from Pauline Newman’s Unpublished Memoir, in Which She Recalls the Beginning of the 1909 Garment Workers’ Strike.” Jewish Women’s Archive, jwa.org/media/excerpt-from-pauline-newman-s-unpublished-memoir-in-which-she-recalls-beginning-of-1909-garmen.

[24] Benoit, Linda. “Who Is Frances Perkins?” Mount Holyoke, www.mtholyoke.edu/fp/frances_perkins.

[25] Brooks, David. “How the First Woman in the U.S. Cabinet Found Her Vocation.” The Atlantic, 14 Apr. 2015, www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/04/frances-perkins/390003/.

[26] Brooks, David. “How the First Woman in the U.S. Cabinet Found Her Vocation.”

[27] Pasachoff. p.24

[28] Pasachoff. p.45

[29] Pasachoff. p.26

[30] Pasachoff. p.24

[31] Brooks, David. “How the First Woman in the U.S. Cabinet Found Her Vocation.”

[32] Pasachoff. p.10

[33] Tyler. p.5

[34] Weir, Robert E. Workers in America: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2013. p.514

[35] Pasachoff. p.24

[36] “National Industrial Recovery Act (1933).” Ourdocuments.gov, www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=66.

[37] O’Farrell, Brigid. “A Stitch in Time The New Deal, The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, and Mrs. Roosevelt.” Open Journals, Transatlantica; American Studies Journal, 2006, journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/190?lang=en.

[38] Tyler. p.200

[39] O’Farrell, Brigid. “A Stitch in Time The New Deal, The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, and Mrs. Roosevelt.”

[40] Tyler. p.15

[41] “Bread and Roses.” Folkarchive.de, www.folkarchive.de/breadrose.html.

[42] Tyler. p.202

[43] Pasachoff. p.46

[44] Pasachoff. p.31

[45] Perkins, Frances. “The Roots of Social Security.” Social Security, www.ssa.gov/history/perkins5.html.

[46] Pasachoff. p.54

[47] Berstein, Irving. “Chapter 5: Americans in Depression and War By Irving Bernstein.” US Department of Labor, www.dol.gov/general/aboutdol/history/chapter5.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Dreier, Peter. “If You Like Social Security and Minimum Wage, Thank Frances Perkins.” HuffPost, 6 Dec. 2017, www.huffpost.com/entry/if-you-like-social-security-and-minimum-wage_b_7475098.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Stillman, Sarah. “Death Traps: the Bangladesh Garment Factory Disaster.” The New Yorker, 1 May 2013, www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/death-traps-the-bangladesh-garment-factory-disaster.

[53] Equal Pay Act of 1963.

[54] Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII).

[55] Soyer. pp.3-26

[56] Stillman, Sarah. “Death Traps: the Bangladesh Garment Factory Disaster.” The New Yorker, 1 May 2013, www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/death-traps-the-bangladesh-garment-factory-disaster.

[57] Safi, Michael, and Dominic Rushe. “Rana Plaza, Five Years on: Safety of Workers Hangs in Balance in Bangladesh.” The Guardian, 24 Apr. 2018, www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/apr/24/bangladeshi-police-target-garment-workers-union-rana-plaza-five-years-on.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Marshall, Tom. “Bangladesh Factory Safety and the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire.” The New York Times, 8 Apr. 2014, learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/04/08/text-to-text-bangladesh-factory-safety-and-the-triangle-shirtwaist-fire/.

[60] Soyer. p.214

[61] Amin, Sajeda. “Responding to Rana Plaza: a Made-in-Bangladesh Boycott Won’t Help Girls.” The Guardian, 30 Apr. 2014, www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2014/apr/30/rana-plaza-boycott-bangladesh-garment-factory.

[62] Ackerly, Brooke. “Creating Justice for Bangladeshi Garment Workers with Pressure Not Boycotts.” The Conversation, 24 Apr. 2015, theconversation.com/creating-justice-for-bangladeshi-garment-workers-with-pressure-not-boycotts-40592.

[63] Hobbes, Michael. “The Myth of the Ethical Shopper.” The Huffington Post, 2015, highline.huffingtonpost.com/articles/en/the-myth-of-the-ethical-shopper/.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ashraf, Hasan, and Rebecca Prentice. “Beyond Factory Safety: Labor Unions, Militant Protest, and the Accelerated Ambitions of Bangladesh’s Export Garment Industry.” Dialectical Anthropology, vol. 43, no.1, 10 Jan. 2019, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10624-018-9539-0.

[66] “Achievements 2013 Accord.” Accord of Fire and Safety in Bangladesh, 20 July 2018, bangladeshaccord.org/2018/07/20/achievements-2013-accord/.

[67] Greenhouse, Steven. “’Some Kids Are Not Orphans Because of This’: How Unions Are Keeping Workers Safe.” The Guardian, 8 Nov. 2017, www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/nov/08/unions-workers-safety-codes-of-conduct-florida-bangladesh.