Vision and Motivation

With the coming of the Mexican Revolution in 1910, many Mexicans fled north to the United States in order to escape the bloodshed in search of new lives. As the influx of migration continued, the American demand for agricultural laborers was so high that a work-visa program for Mexicans was established in 1920. While the Bracero Program offered Mexican farmworkers a legally binding work contract, the majority suffered gross abuses of their labor rights and racial discrimination.

With the coming of the Mexican Revolution in 1910, many Mexicans fled north to the United States in order to escape the bloodshed in search of new lives. As the influx of migration continued, the American demand for agricultural laborers was so high that a work-visa program for Mexicans was established in 1920. While the Bracero Program offered Mexican farmworkers a legally binding work contract, the majority suffered gross abuses of their labor rights and racial discrimination.

Farmworkers were often unpaid and were denied the right to unionize, a right that all other American workers enjoyed. They labored in inhumane conditions, as growers ignored state laws on working conditions. The workers had no toilets to use in the fields, and were forced to pay two dollars or more per day to live in metal shacks with no plumbing or electricity. On top of that, grape pickers were paid an average of 90 cents per hour, plus ten cents per basket picked, placing their families well below the poverty line.[1]

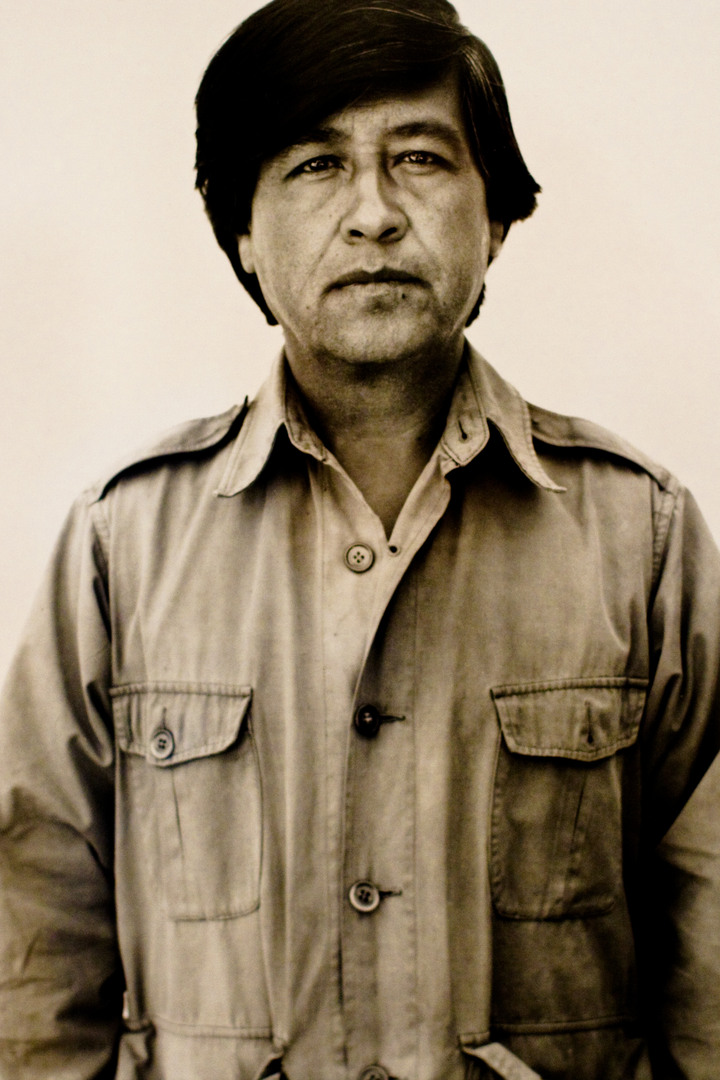

Cesar Chavez was born to a Mexican-American family in Arizona in 1927. As the Great Depression devastated the American economy, his family lost their farm and business, and in 1937 they moved to California. There, the Chavez family worked in the fields, moving from farm to farm with the seasons. In the early 1940s, the family settled in Delano, a farm town in the San Joaquin valley that would become the epicenter of a groundbreaking movement for farmworkers’ rights in the 1960s.[2]

Goals and Objectives

Chavez’s ultimate goal was “to overthrow a farm labor system in this nation which treats farm workers as if they were not important human beings.”[3] In 1962, he founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which would form the backbone of his labor campaigns. [4] Chavez wanted the dignity and rights of farmworkers to be respected. “We demand to be treated like the men we are! We are not slaves and we are not animals,” he said.[5]

In September 1965, the Delano Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), mostly made up of Filipino grape pickers, went on strike, demanding payment of $1.40 an hour plus 25 cents per box of grapes picked.[6] AWOC’s leader knew that a successful strike must include not only Filipino workers but also the many Mexican and Chicano workers in Delano. He reached out to Chavez and the NFWA, who gave him their support and expanded the strike’s goals to include union contracts signed by the growers and laws allowing farmworkers to unionize and engage in collective bargaining.[7]

In September 1965, the Delano Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), mostly made up of Filipino grape pickers, went on strike, demanding payment of $1.40 an hour plus 25 cents per box of grapes picked.[6] AWOC’s leader knew that a successful strike must include not only Filipino workers but also the many Mexican and Chicano workers in Delano. He reached out to Chavez and the NFWA, who gave him their support and expanded the strike’s goals to include union contracts signed by the growers and laws allowing farmworkers to unionize and engage in collective bargaining.[7]

In the summer of 1967, Chavez shifted his focus from the strike to a nationwide boycott of California grapes in support of farmworker rights. A vast network of activists urged consumers to boycott grapes, and pressured supermarket chains to not buy grapes, in an effort to bring attention to the plight of the farmworkers, thus pressuring the growers to sign contracts with their employees.

Leadership

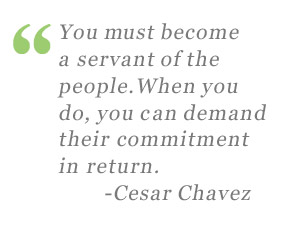

Chavez’s leadership was based on an unshakeable commitment to non-violence, personal sacrifice, and a strict work ethic.[8] Having devoted his life to the cause, he demanded great dedication from his supporters. Chavez said, “You must become a servant of the people. When you do, you can demand their commitment in return.”[9]

Chavez’s leadership was based on an unshakeable commitment to non-violence, personal sacrifice, and a strict work ethic.[8] Having devoted his life to the cause, he demanded great dedication from his supporters. Chavez said, “You must become a servant of the people. When you do, you can demand their commitment in return.”[9]

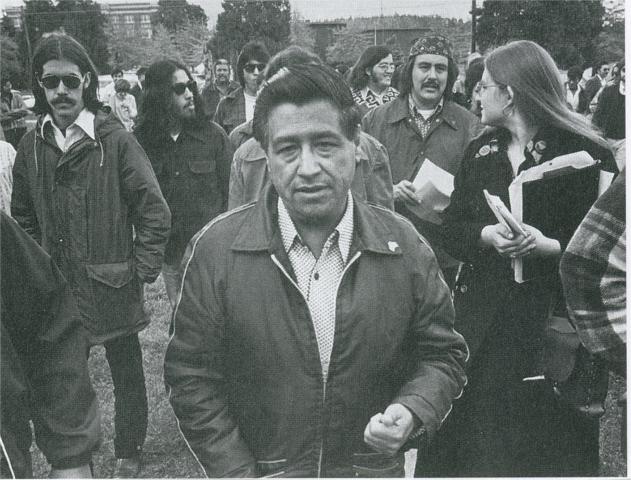

In the early years of the NFWA, through perseverance, he slowly won over skeptical workers who had seen dozens of failed strikes. Chavez first worked to learn what workers wanted. He drew a map of the Delano valley and pinpointed 86 towns to target, and then his volunteers fanned out across homes and grocery stores to distribute registration cards asking for a name, address, and answer to questions about their wages and lack of Social Security and unemployment benefits. He and other volunteers then went door-to-door to recruit supporters.[10]

Chavez emphasized the necessity of adhering to nonviolence, even in the face of violence from growers. “We are convinced that non-violence is more powerful than violence,” he wrote. “We are convinced that non-violence supports you if you have a just and moral cause.”[11] Moreover, he knew that if the strikers used violence, the growers and the police would not hesitate to quell the strike with violence.

Civic Environment

The Delano growers were powerful, with many connections to the police, judges, and politicians in the community; they had accumulated vast wealth over the years and were loath to give any of it up. They hired armed security guards to intimidate the strikers. Picketers were sprayed with pesticides, threatened with dogs, verbally assaulted, and physically attacked.[12] Chavez responded by sending his allies in the clergy to walk the picket lines “as a reminder to police, grower security guards, and growers that the rest of the world was watching.”[13]

The Delano growers were powerful, with many connections to the police, judges, and politicians in the community; they had accumulated vast wealth over the years and were loath to give any of it up. They hired armed security guards to intimidate the strikers. Picketers were sprayed with pesticides, threatened with dogs, verbally assaulted, and physically attacked.[12] Chavez responded by sending his allies in the clergy to walk the picket lines “as a reminder to police, grower security guards, and growers that the rest of the world was watching.”[13]

Growers smeared Chavez’s coalition as a group of dangerous “outside agitators” who were disrupting a peaceful community; they insisted that the workers “are extremely happy. If they weren’t, they would not be coming here…These men have chosen this type of work…We think that we have tried to better their lot.”[14]

Police conducted surveillance of strikers, photographing them and recording their names. The county sheriff cracked down by forbidding strikers to “disturb the peace” by gathering and shouting on roadsides; he then went so far as to ban the use of the word huelga (Spanish for “strike”). In response, Chavez decided to force a confrontation; his supporters deliberately disobeyed these edicts – in front of television and newspaper reporters – and were arrested. Meanwhile, Chavez, who was touring state universities, used this repression to rally support from students, who donated $6,700 to the cause. The sheriff’s order was later declared unconstitutional.[15]

Message and Audience

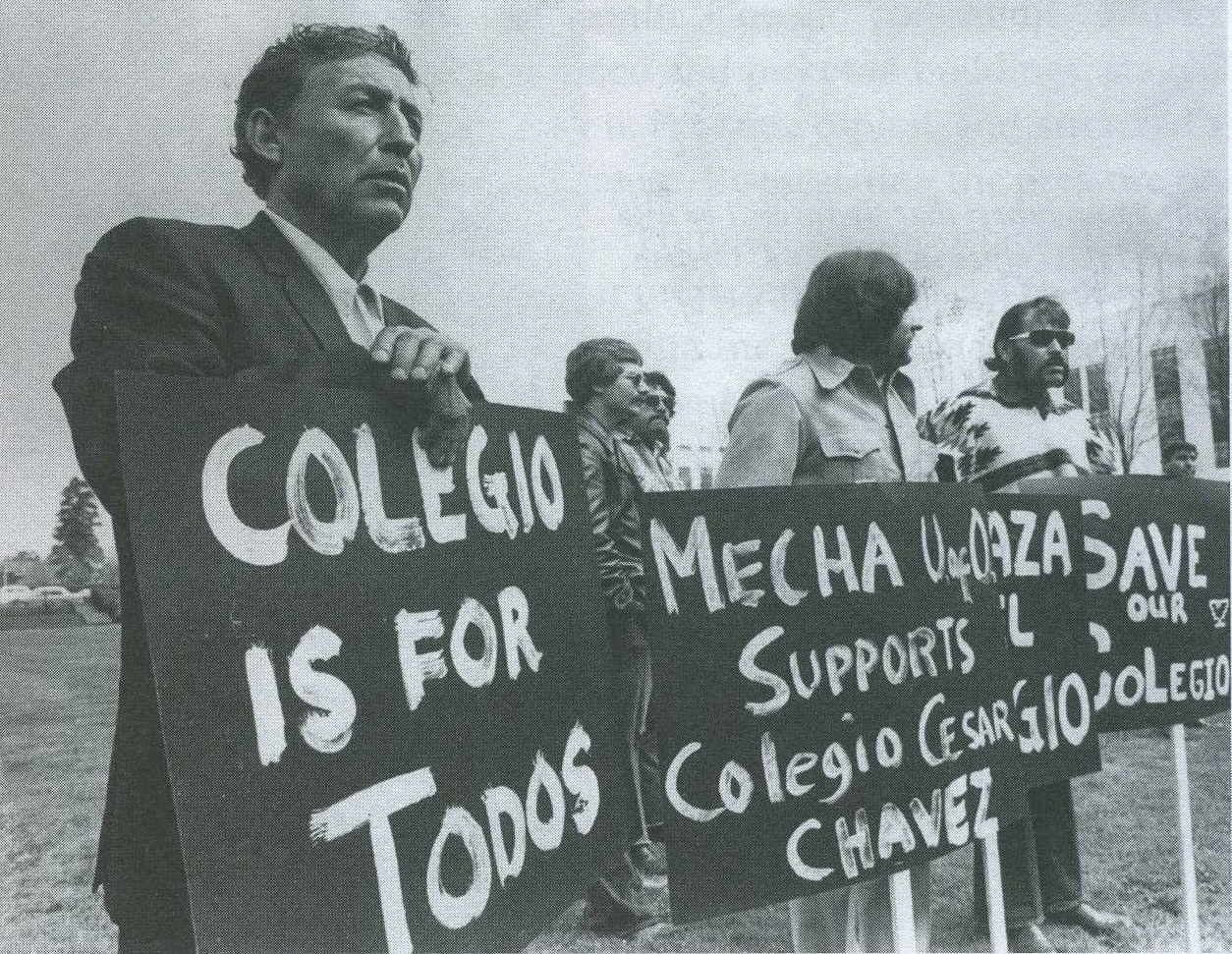

Chavez strove for better wages and working conditions, but more than that, he strove to spread a message of dignity, respect, and justice for farmworkers.[16] To communicate this message, he chose for a symbol a black Aztec eagle, because “It gives pride…When people see it, they know it means dignity.”[17] As the Delano strike began, Chavez took care to frame it not as a mere union dispute but as the beginning of a movement – a struggle for not just a goal, but a cause. The slogan strikers chanted was “Viva la causa!” – “Long live the cause!”

In December 1964, the NFWA launched its newsletter, El Malcriado or The Voice of the Farmworker. Written with humor and irreverence, it publicized stories of struggle against the growers’ oppression and used cartoons of characters workers could identify with in order to communicate to the illiterate. The hugely popular newsletter was distributed at barrio grocery stores and sold at fundraising barbeques.[18]

El Malcriado was also used to mobilize supporters by publicizing the 1965 Delano strike. With NFWA members’ support, the strike immediately spread from 20 labor camps to 48.[19] Meanwhile, el Teatro Campesino, the Farm Workers’ Theater, staged clever, humorous skits from the backs of trucks to entertain the strikers and attract others to join the cause. This bilingual street theater group made up of ordinary farm workers used comedy to teach their audience about their rights.[20]

Chavez also needed to publicize the situation across the country. In December, he launched a boycott of two of Delano’s main growers, Schenley Industries and DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation. But after strikers’ spirits began to flag, in March 1966, Chavez organized a massive march of 300 miles from Delano to Sacramento, the state capital – the longest protest march ever in the United States. Not only was it a march, it was a pilgrimage that drew upon the Catholic faith of many of the strikers. Marchers sang “Nosotros Venceremos” – the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome” – as they carried portraits of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico’s matron saint and a symbol of hope, as well as large crosses representing Christ’s final journey and flags including the NFWA’s black eagle.[21]

Chavez also needed to publicize the situation across the country. In December, he launched a boycott of two of Delano’s main growers, Schenley Industries and DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation. But after strikers’ spirits began to flag, in March 1966, Chavez organized a massive march of 300 miles from Delano to Sacramento, the state capital – the longest protest march ever in the United States. Not only was it a march, it was a pilgrimage that drew upon the Catholic faith of many of the strikers. Marchers sang “Nosotros Venceremos” – the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome” – as they carried portraits of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico’s matron saint and a symbol of hope, as well as large crosses representing Christ’s final journey and flags including the NFWA’s black eagle.[21]

As the march wound its way across California, excitement built, and in each town they passed through, they attracted new supporters, as well as media coverage.[22] During the final leg of the journey, a Schenley Industries lawyer called, wanting to sign a contract. Schenley agreed to recognize the NFWA, give workers a raise of 35 cents an hour, and build a hiring hall for the workers.[23] It was the movement’s first tangible victory.

However, the massively powerful DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation was still refusing to give in, and after seven months of striking, the workers were again losing momentum. As some returned to work, Chavez secretly got them to strike from within the ranch, by developing an inside network of informants, persuading other workers to support the union, and engaging in tactical slowdowns of work.[24]

In late May, Chavez launched a “pray-in” across from the DiGiorgio ranch entrance. For months, hundreds of farm workers flocked to a wooden altar set up on the back of Chavez’s station wagon to pray for elections and contracts. Meanwhile, the boycott spread, and the movement also began to block grapes from leaving distribution centers across the country.[25] DiGiorgio was worn down, and offered to hold union elections; however, they then rigged the elections so strikers could not vote. In response, Chavez pulled the NFWA off the ballot and called for a boycott of the elections.[26]

Ultimately, the governor of California ordered a new election to be held in September. To bolster their strength, the NFWA and AWOC merged, becoming the United Farm Workers of America (UFWA).[27] Organizers traveled as far as Texas and Oregon to track down and bring back strikers who had left California.[28] They set up a database tracking workers and their possible votes as they worked to win support, and on election day, volunteers picked up all the pro-union voters and drove them to the polls.[29] The UFW won the field worker vote in a victory that bolstered their credibility as well as their position within the overall labor movement.[30]

However, the battle to win contracts wore on. Chavez recognized that he could not win in the fields alone, due to the growers’ ability to bring in strikebreakers from Mexico.[31] So he shifted his campaign’s focus from the fields to the supermarkets. He sought to shut down the consumer market for grapes.[32] In the summer of 1967, volunteers fanned out across the country, using labor and church contacts to set up networks of support and spread the message “Don’t buy grapes.”[33] Activists spread the word via mailing lists, letters to the editor, media interviews, public speeches, and debates.[34] They would ask store owners not to buy grapes; if they refused, activists would picket the store and call for a store boycott.[35]

However, the battle to win contracts wore on. Chavez recognized that he could not win in the fields alone, due to the growers’ ability to bring in strikebreakers from Mexico.[31] So he shifted his campaign’s focus from the fields to the supermarkets. He sought to shut down the consumer market for grapes.[32] In the summer of 1967, volunteers fanned out across the country, using labor and church contacts to set up networks of support and spread the message “Don’t buy grapes.”[33] Activists spread the word via mailing lists, letters to the editor, media interviews, public speeches, and debates.[34] They would ask store owners not to buy grapes; if they refused, activists would picket the store and call for a store boycott.[35]

In February 1968, as some supporters called for less peaceful approaches to civic action, Chavez decided to embark on a “fast for nonviolence and a call to sacrifice,” an act of penance that would demonstrate the discipline necessary to wage a nonviolent civic struggle.[36] It resonated with deeply religious workers, who flocked to Delano in support of Chavez. After 25 days, he broke his fast in a gathering that included Senator Robert Kennedy.

In July 1969, Chavez made the cover of Time magazine, and as he became a national leader, he embarked on a 28-city tour of the United States, giving speeches that helped rally support for the grape boycott.[37] Finally, in the spring of 1970, smaller grape growers who were harder-hit by the boycott signed contracts with the union, ending a long and painful economic boycott.[38] As these growers’ grapes were now union-approved, they sold for premium prices across the country, increasing the pressure on other growers.

At that point, 25 large growers entered into negotiations and signed contracts.[39] 10,000 workers were now given formal union representation, a higher wage ($1.80 plus 20 cents for each box picked, as compared to the pre-strike wage of $1.10 an hour), a health insurance plan, and safety limits on the use of pesticides in the fields.[40] After a five year long struggle, the workers had won not just better wages and working conditions, but a renewed sense of dignity.

Outreach Activities

From the beginning, Chavez reached out beyond the farmworker community to build a broad coalition consisting of civil rights activists, students, labor, and churches. The movement’s support from the church sent the message that this was a mainstream, non-radical cause that was safe for community members to join; it also gave volunteers a kind of moral authority and provided a vital network for grassroots activists across the country.[41]

Chavez traveled to not only churches to request donations and support, but also to university campuses. Liberal student activists and civil rights volunteers from the Congress of Racial Equality and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee joined the movement.[42] Support for the movement crossed racial lines, including Mexican and Filipino workers, as well as black and white activists. During Chavez’s 1968 hunger strike, Martin Luther King, Jr. sent him a telegram saying, “Our separate struggles are really one. A struggle for freedom, for dignity, and for humanity.”[43]

Organized labor provided essential support to the movement, as unions both inside and outside the United States were able to add leverage to the boycott and help stop grape shipments. The movement drew political support from Senator Robert Kennedy, who helped lead Senate hearings on the strike and even demonstrated his support by joining a picket line.[44] It also won the support of the white-collar Mexican-American Political Association, giving the union additional political influence.[45]

Organized labor provided essential support to the movement, as unions both inside and outside the United States were able to add leverage to the boycott and help stop grape shipments. The movement drew political support from Senator Robert Kennedy, who helped lead Senate hearings on the strike and even demonstrated his support by joining a picket line.[44] It also won the support of the white-collar Mexican-American Political Association, giving the union additional political influence.[45]

These diverse sources of support were an essential element of the movement’s victory. Despite later setbacks, such as an unsuccessful lettuce boycott and a failed grape boycott aimed at ending the use of pesticides in the fields, Chavez continued to fight for farmworkers’ rights with a steadfast commitment to nonviolence until his death in 1993. For his tireless efforts for farmworkers’ rights, Chavez’s birthday became a celebrated state holiday in California, and he was posthumously awarded the 1994 Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton. His work still resonates today; as Chavez said, “Once social change begins, it cannot be reversed. You cannot uneducate the person who has learned to read. You cannot humiliate the person who feels pride. And you cannot oppress the people who are not afraid anymore.”[46]

Learn More

News & Analysis

Cesar E. Chavez Foundation website.

The Farmworker Movement Documentation Project. Si Se Puede Press.

“The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers’ Struggle.” PBS.

“The Little Strike that Grew to La Causa.” Time. 4 July 1969.

Books

Ferriss, Susan and Ricardo Sandoval. The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement. Orlando: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1997.

Ganz, Marshall. Why David Sometimes Wins: Leadership, Organization, and Strategy in the California Farm Worker Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Levy, Jacques E. and Cesar Chavez. Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa. New York: Norton, 1975.

Orosco, Jose-Antonio. Cesar Chavez and the Common Sense of Nonviolence. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008.

Pawel, Miriam. The Union of Their Dreams: Power, Hope, and Struggle in Cesar Chavez’s Farm Worker Movement. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2009.

Shaw, Randy. Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, the UFW, and the Struggle for Justice in the 21st Century. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California, 2008.

Multimedia

“Cesar Chavez on the Delano Grape Strike.” KPFA radio. Berkeley, CA. 15 Jan. 1966.

“Cesar Chavez at New York City College.” BB3147. New York, NY. 16 May 1968.

“The Life and Legacy of Cesar Chavez.” YouTube.

Footnotes

[1] “UFW History.” United Farm Workers website.

[2] Tejada-Flores, Rick. “Cesar Chavez.” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States. Oxford University Press, 2004.

[3] Chavez, Cesar. “Address to the Commonwealth Club of California.” San Francisco, CA. 9 Nov. 1984.

[4] Tejada-Flores.

[5] Chavez, Cesar. “The Union and the Strike.” Cesar Chavez Foundation website.

[6] Ganz, Marshall. Why David Sometimes Wins: Leadership, Organization, and Strategy in the California Farm Worker Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. p.123.

[7] “The Story of Cesar Chavez.” United Farm Workers of America website.

[8] Pawel, Miriam. The Union of Their Dreams: Power, Hope, and Struggle in Cesar Chavez’s Farm Worker Movement. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2009. p.56.

[9] Chavez, Cesar. “Education of the Heart: Quotes by Cesar Chavez.” United Farm Workers website.

[10] Ferriss, Susan and Ricardo Sandoval. The Fight in the Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement. Orlando: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1997. p.67.

[11] “Education of the Heart: Quotes by Cesar Chavez.”

[12] Ferriss and Sandoval, p.96.

[13] Pawel, p.18.

[14] Ferris and Sandoval, pp.97-8.

[15] Ibid., 106-7.

[16] Pawel, pp. 24, 71.

[17] “The Story of Cesar Chavez.” United Farm Workers of America website.

[18] Ferris and Sandoval, pp. 80-1.

[19] Ibid., 89.

[20] Ibid., 101.

[21] Ibid., 119.

[22] Ibid., 120.

[23] Ibid., 121-2.

[24] Ibid., 127-8.

[25] Ibid., 128.

[26] Pawel, p. 25.

[27] Ferris and Sandoval, p. 131.

[28] Pawel, p. 27.

[29] Ibid., 28.

[30] Ibid., 30.

[31] Ibid., 51.

[32] Ibid., 31.

[33] Ibid., 32.

[34] Ibid., 35.

[35] Ibid., 34, 39.

[36] Ibid., 41, 43, 46.

[37] Ibid., 54.

[38] Ibid., 61.

[39] Ibid., 63.

[40] Bruns, Roger. Cesar Chavez: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2005. p.68.

[41] Shaw, Randy. Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, the UFW, and the Struggle for Justice in the 21st Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008. p.37.

[42] Ferris and Sandoval, p.102.

[43] Chavez, Cesar. “Lessons of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.” 12 Jan. 1990.

[44] Ferris and Sandoval, p. 117.

[45] Ibid., 130.

[46] “Lessons of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.”