Vision and Motivation

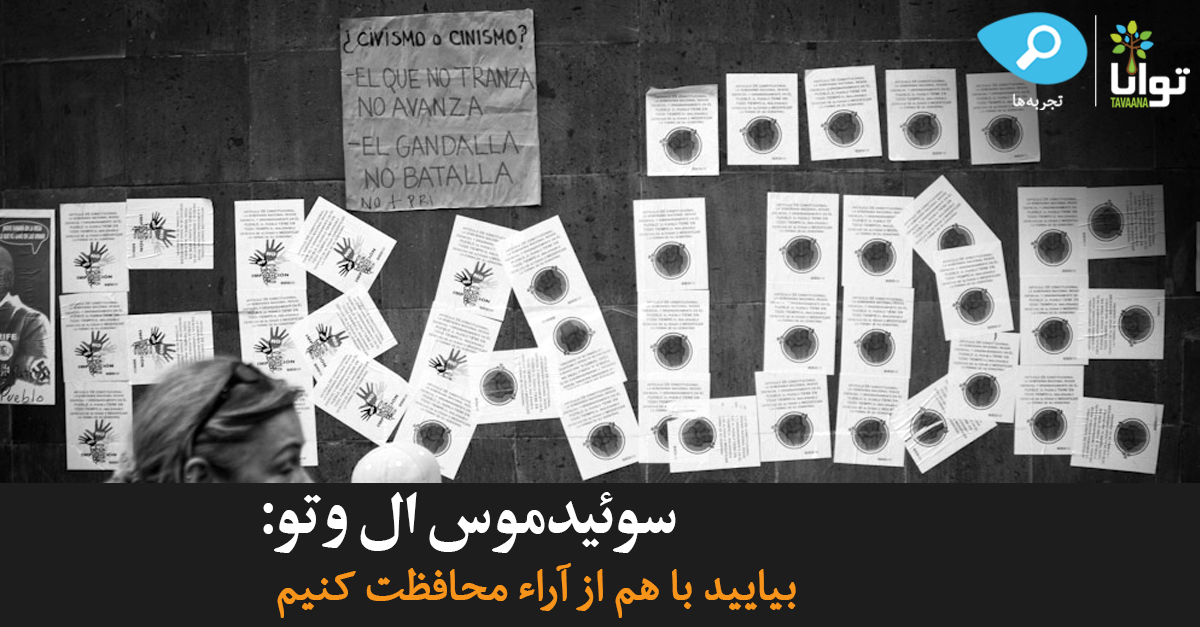

Despite the passage of a number of electoral reforms in Mexico in the 1990s, most Mexicans lacked trust in the integrity of the electoral process, which had for years been marred by corruption. When the National Action Party’s (PAN) Vicente Fox won the presidential election on July 2, 2000, it marked the first victory by an opposition party since the 1910 Mexican Revolution. Political analysts lauded the election as a major step in consolidating Mexico’s transition to democratic governance. Serious allegations of election fraud continued into the 21st century, however. In the July 2006 presidential election, opposition candidate Andrew Manuel Lopez Obrador raised claims of fraud at 50,000 polling stations and organized mass protests that brought the capital to a standstill for the entire month of August.[1]

In May 2009, Oscar Salazar, a Mexican consultant to the United Nations Development Program in New York, was looking for new digital tools to help Mexican civil society. After being introduced to Andres Lajous, a fellow Mexican and prominent political activist studying at MIT, the two began discussing mobile technology and governance in Mexico, as well as ways to improve political transparency and citizen engagement. According to Salazar, “We were reading a lot of reports saying that elections in Mexico were not corrupt anymore…we wanted to find out if that was the case or not.” With federal elections just two months away, the two set out to map and monitor electoral misconduct using a new crowd-mapping tool called Ushahidi, enabling Mexicans to use their cell phones, cameras and computers to contribute eyewitness reports of voter fraud. They called their initiative Cuidemos el Voto, which means ‘Let’s protect the vote together’.[2]

Goals and Objectives

“Our main goal was civic engagement – to bring young Mexicans into the democratic process, because democracy isn’t perfect if young people aren’t participating,” explained Salazar. As a technology tool, Ushahidi offered Salazar and Lajous the perfect opportunity to bolster the involvement and participation of Mexican youth in elections because of the platform’s mobile compatibility and reliance upon user-generated data.[3] Meaning “witness” in Swahili, Ushahidi is a platform that was initially developed to map reports of violence in the aftermath of Kenya’s disputed 2007 presidential election, and has since been adopted by emergency relief workers in Haiti, citizen firefighters in Russia and anti-trafficking activists around the world. The tool enabled Kenyans to report and map incidents of violence that they witnessed via SMS, email, or the web. Since its African inception, Ushahidi has served as a prototype for what can be done by combining crisis information from citizen-generated reports, media and NGOs and mashing that data up with geographical mapping tools.[4]

An open-source crisis-mapping software called Ushahidi was developed to map reports of violence in Kenya after the post-election fallout at the beginning of 2008. It kept Kenyans current on vital information and provided valuable assistance to relief workers in the field by enabling citizens on the ground to report acts of violence via SMS, e-mail, photos and audio files, which were then uploaded to an interactive map made publicly available on the Internet. For the most part, Ushahidi users contribute reports via SMS, so the platform provides a unique and direct link to the Internet, turning ‘dumb’ phones into smarter mobile devices.

As events occur in the field, SMS messages are sent to a designated phone number and stored in a secure database, where Ushahidi administrators can view them. If more information is needed to confirm the report, administrators have the ability to reply to messages; in addition to fact-checking submissions, administrators are tasked with prioritizing the urgency of each report. By tracking the GPS coordinates of each SMS, administrators can post a title and description of each report onto an interactive map. Once the point of interest is added to the map, administrators have the ability to add time-sensitive and geo-targeted alerts for journalists, NGOs, relief workers and civic activists to quickly respond to incidents as they occur. After the data has been collected, the Ushahidi platform develops a full analytical report that identifies areas with high-levels of reporting, as well as a full timeline of events, and can serve as actionable evidence for media, human rights defenders, election monitoring agencies and other civic institutions. Since its initial development in 2008, it has increased its accessibility to other mobile technologies such as J2Me, WinMo, Android and FrontlineSMS, and has incorporated additional mapping applications from OpenLayers, Yahoo, Microsoft and OSM, which enables the platform to plot larger data sets.[5]

What is the Ushahidi Platform? from Ushahidi on Vimeo.

Because of its effectiveness, Ushahidi has been deployed for a variety of uses all over the world. As a system for reporting electoral fraud, Ushahidi has been implemented in Kenya, Turkey, Mexico, Cote d’Ivoire, Uganda, Sudan and India. In an effort to map human rights violations, NGOs have adopted Ushahidi in Syria, Tibet, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Egypt Turkey and Libya, while others are using it to provide emergency relief during environmental disasters in Haiti, Russia, Chile, Pakistan, Canada, the Philippines and the United States.[6]

Participation from everyday citizens was of paramount importance, so Salazar and Lajous were tasked with pitching the platform to the everyday Mexican.[7] “We had to gain trust from them and not only implement the pilot, but also the ideal that average citizens can become their own police and supervise elections,” recalled Salazar.[8] In order to gain credibility and legitimacy in Mexican civil society, Salazar and Lajous partnered with local NGOs, industry organizations and universities and trained their staff members and election monitors to use Ushahidi in their own election monitoring processes. In addition to holding “train the trainer” sessions, the two activists were able to exponentially increase the number of contributors to Cuidemos el Voto by engaging influential civic activists via Twitter, who in turn informed their followers.

With Cuidemos el Voto gaining popularity among NGOs and even political parties in the weeks prior to the election, the platform quickly began piling up citizen reports of misconduct. The Ushahidi-generated reports offered a clear geographic picture of actionable evidence for official election monitoring agencies, as well as for journalists, who had the option of receiving SMS alerts when events occurred near them. As the data poured in, Salazar and Lajous understood the need to remain fair and impartial, and Salazar emphasized “by making the platform transparent, we were telling everybody that by playing with us, they would have to follow certain rules.”[9]

Leadership

With a PhD in telecommunications, Salazar is a technologist by trade, having spent over 10 years implementing local e-government initiatives in Mexico. In 2009, he was working as a consultant on mobile technology and governance for the United Nations Development Program and the Inter American Development Bank in New York, looking for new tools to improve Mexican civil society. After discovering Ushahidi in the spring of 2009, Salazar reached out to a professor at MIT with expertise in information communication technologies (ICT), who suggested that he speak to one of his top students, well-known Mexican political activist Andres Lajous.

With a PhD in telecommunications, Salazar is a technologist by trade, having spent over 10 years implementing local e-government initiatives in Mexico. In 2009, he was working as a consultant on mobile technology and governance for the United Nations Development Program and the Inter American Development Bank in New York, looking for new tools to improve Mexican civil society. After discovering Ushahidi in the spring of 2009, Salazar reached out to a professor at MIT with expertise in information communication technologies (ICT), who suggested that he speak to one of his top students, well-known Mexican political activist Andres Lajous.

At his professor’s mention of the opportunity, Lajous enthusiastically reached out to Salazar and booked a train ticket to New York in early May 2009. With his grassroots activism experience and understanding of local Mexican politics, Salazar had found the ideal partner to complement his technology skills. With little time to waste before the July elections, the two quickly returned to Mexico to establish Cuidemos el Voto.[10]

Civic Environment

Since Mexico’s peaceful transition of power to an opposition party in 2000, the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE), which serves as the independent body for election monitoring, has been lauded as a model for other countries. According to Freedom House, Mexican elections have been free and fair, but at the same time, many complaints about bribery and politically motivated crime continue to surface during election years, exemplified by the scores of protests led by Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador after he lost the 2006 presidential election. Despite the fact that many Mexicans and international observers were not convinced by Obrador’s allegations of fraud, i.e. negative advertising and the use of administrative resources on behalf of the victor, a series of electoral reforms were passed in 2007 that hoped to reach a higher level of electoral fairness.[11]

Despite countless reforms, Salazar explained, “People are getting tired of reporting anything because nothing happens. They say ‘OK everything is corrupt, so if I complain or if I report, it’s not going to change anything.”[12] Senior officials are constantly charged with links to drug traffickers, but are rarely convicted of a crime or dismissed from their bureaucratic duties. In Transparency International’s 2009 Corruption Perceptions Index, Mexico was ranked 89 out of 180 countries.[13] By implementing Ushahidi in Mexico, Salazar and Lajous created a fraud reporting mechanism that, for the first time, empowered civic activists and election monitors to produce their own courtroom-quality documentation.

Message and Audience

“We want [Cuidemos el Voto] to be for Mexicans, so we had to identify the right cultural messages to attract users and identify with it, so we went with the Luchador,” described Salazar.[14] The luchador, a traditional masked wrestler, is a popular symbol in Mexican society for super-human ability and strength, which the campaign used to emphasize the importance of protecting the votes of all Mexicans. By taking the colors of the Mexican flag and saturating them with an Andy Warhol-like effect, Cuidemos el Voto created a fun and engaging pop-culture image that resonated well with Mexican youth.[15]

“We want [Cuidemos el Voto] to be for Mexicans, so we had to identify the right cultural messages to attract users and identify with it, so we went with the Luchador,” described Salazar.[14] The luchador, a traditional masked wrestler, is a popular symbol in Mexican society for super-human ability and strength, which the campaign used to emphasize the importance of protecting the votes of all Mexicans. By taking the colors of the Mexican flag and saturating them with an Andy Warhol-like effect, Cuidemos el Voto created a fun and engaging pop-culture image that resonated well with Mexican youth.[15]

With an advertising budget of just $200, Cuidemos el Voto took to the Internet to engage Mexican youth, leveraging social media sites like Twitter and Facebook to reach their target audience. According to Salazar, “We use social media to reach certain points of the population, which in this case was 18-24 year olds. They are all heavy social media users and early adopters of the technology, so we needed to use a channel that was already open.” Additionally, Twitter enabled the campaign to reach important journalists and secure interviews with a significant number of Mexican media outlets.[16]

Outreach Activities

While Cuidemos el Voto has yet to bring about significant changes in regard to Mexico’s corruption, it has fulfilled its primary goal of increasing citizen engagement in the political process. Salazar and Lajous have empowered everyday Mexicans with the ability to create and report actionable evidence for official election monitoring agencies. By turning voters into grassroots election monitors, Cuidemos el Voto enables citizens to have an active stake in the fight against corruption, giving them the potential to forever change citizens’ expectations and the political culture surrounding Mexican elections.

While Cuidemos el Voto has yet to bring about significant changes in regard to Mexico’s corruption, it has fulfilled its primary goal of increasing citizen engagement in the political process. Salazar and Lajous have empowered everyday Mexicans with the ability to create and report actionable evidence for official election monitoring agencies. By turning voters into grassroots election monitors, Cuidemos el Voto enables citizens to have an active stake in the fight against corruption, giving them the potential to forever change citizens’ expectations and the political culture surrounding Mexican elections.

Moreover, using the same grassroots strategy on a more localized level, Cuidemos el Voto is committed to improving the capacity of local civil society organizations to promote active citizenship, and has since partnered with neighborhood and regional civil society organizations around Mexico to setup localized Ushahidi platforms for future city-wide and regional elections. It is active citizens that Salazar hopes the whole of Mexico will become because, in his words, “If people do not trust their government, they are just people, not citizens.”[17]

Learn More

News & Analysis

“Country Report: Mexico (2010).” Freedom House. 2010.

“Home page.” Cuidemos el Voto. 2009.

“Home page.” MIT Center for Future Civic Media. 2010.

Ramey, Corrine. “Mexicans report votes (and nonvotes) with SMS.” MobileActive. 19 June 2009.

Rotich, Juliana. “Cuidemos el Voto: Monitoring Federal Elections in Mexico.” Ushahidi. 25 June 2009.

Vila, Susannah. “Cuidemos el Voto.” Alliance for Youth Movements. 2010.

Vila, Susannah. “Cuidemos el Voto.” Technology for Transparency network. 27 April 2010.

Footnotes

[1] “Mexico Court Rejects Fraud Claim.” BBC News. 29 Aug 2006.

[2] Vila, Susannah. “Cuidemos el Voto.” Technology for Transparency network. 27 April 2010.

[3] Salazar, Oscar. Personal Interview (Skype). 15 Nov 2010.

[4] “Ushahidi 1-Pager.” Ushahidi. 2010. PDF.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Deployments.” Ushahidi website. 13 June 2011.

[7] “Ushahidi 1-Pager.”

[8] Vila.

[9] Salazar.

[10] Ibid.

[11] “Country Report: Mexico (2010).” Freedom House. 2010.

[12] Vila.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Salazar.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Salazar, Oscar. Tech@State Conference. World Bank, Washington, DC. 4 May 2010.