“Whenever you can, act as a liberator. Freedom, dignity, wealth–these three together constitute the greatest happiness of humanity. If you bequeath all three to your people, their love for you will never die.”[1]

Vision and Motivation

In 550 B.C., Cyrus, king of Anshan, founded the Achaemenid Empire by conquering the kingdom of Media. During Cyrus’s reign – from 550 until 530 B.C. – the Achaemenid territory stretched from the Balkans to Central Asia.[2]The Achaemenid Empire was the largest empire by the percentage of the world population in history; approximately 59 million of the world’s 112 million people at that time, i.e. 44 percent of the world population, lived under its rule.[3] It was also the most diverse and pluralistic empire in the world at the time, unifying different nations, tribes, languages, cultures and religions. Tolerance was one of its most defining characteristics.[4]

One of the most important events that happened during the reign of Cyrus was his defeat of the Babylonian king Nabonidus and subsequent conquest of Babylon. This conquest was important for two reasons. First, it gave Cyrus control of strategic trade routes in the region.[5] Second, it spurred Cyrus to issue a charter, known as the Cyrus Cylinder, through which he proclaimed his views on the rights of the nations and peoples under his rule. This action has brought Cyrus fame throughout history. The Cyrus Cylinder first describes how Cyrus and his army conquered Babylon and defeated Nabonidus. It then promises freedom of religion and worship for the diverse groups of people living in the Achaemenid Empire. Lastly, the Cylinder grants permission to those who were transferred to Babylon as prisoners of war to return to their homeland. One of the groups allowed to return was the Jewish people. The emperor even gave them financial and political support to return to their homeland and rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem.[6] For these reasons, the Cyrus Cylinder is an important legal document in history that supports religious freedom and tolerance.[7]

Professor Richard Frye, a renowned expert in Iranian and Central Asian studies, notes that “[T]he figure of Cyrus has survived throughout history as more than a great man who founded an empire. He became the epitome of the great qualities expected of a ruler in antiquity, and he assumed heroic features as a conqueror who was tolerant and magnanimous as well as brave and daring. His personality as seen by the Greeks influenced them and Alexander the Great, and, as the tradition was transmitted by the Romans, may be considered to influence our thinking even now.”[8]

Goals and Objectives

Cyrus was far different from other kings of his time in the ways he chose to rule. He adopted tolerance and respect for other’s beliefs, traditions, and customs as the foundations of his policies. This earned him the respect and honor of all people under his rule and secured the integrity of his world empire. After his conquest of Babylon, Cyrus introduced himself as a liberator and the legitimate successor to the vanquished king rather than a conqueror. He did not force people under his rule to change their religion or beliefs. To the contrary, by undertaking actions that supported local populations such as permitting the Jews to return to Judea, their homeland, and helping them to reconstruct the Temple in Jerusalem, Cyrus sought to establish political stability, order and peace in his vast and diverse empire.[9] The most important document portraying Cyrus as “restorer of order and messenger of peace in the world”[10] is the Cyrus Cylinder:

“My vast troops were marching peaceably in Babylon, and the whole of [Sumer] and Akkad had nothing to fear. I sought the safety of the city of Babylon and all its sanctuaries. As for the population of Babylon […, w]ho as if without div[ine intention] had endured a yoke not decreed for them, I soothed their weariness; I freed them from their bonds.”[11]

In historical Hebrew and Babylonian sources, Cyrus is referred to as a reformer and liberator in territories where rulers were deemed incompetent and a source of dissatisfaction among the people and gods. Most importantly Cyrus introduced a different approach and attitude towards religious tolerance in the region.[12] Subsequent Achaemenid emperors, for example Cambyses and Darius, continued Cyrus’s policies and allowed the satrapies (provinces of the Achaemenid Empire) to maintain their own laws, and religious and cultural values. This religious tolerance proved to strengthen the political stability and success of the Achaemenid Empire.

Many scholars believe that Cyrus’s policies find their roots in Zoroastrian teachings.[13] It cannot, however, be ignored that political considerations played an important role in Cyrus policy choices. Administering the vast territories of the Achaemenid Empire as well as preventing rebellions required Cyrus to pursue an ideological strategy that enabled him to collaborate with local elites. His desire to do so is one of the main reasons why Cyrus pursued a policy of allowing local customs to continue without disruption and presenting himself as the guardian of all temples and sanctuaries.[14] Time and again, Cyrus successfully co-opted local clergy and elites and incorporated them into his new ruling structure. [15]Cyrus would also grant limited local political autonomy in ways that benefited him. For example, historians believe that one of Cyrus’s purposes in allowing the Jews to return to Judea was to use them as a barrier between his dominions and those of the Egyptians.[16]

Leadership

When Cyrus the Great succeeded his father Cambyses I, it was in the capacity of the ruler of the Persian district of Anshan, an important Elamite region in ancient Persia, located in today’s western Fars province. Initially, he was not a fully independent sovereign but owed allegiance to the king of Media. In 553 B.C., Cyrus rebelled against Astyages, the last Median king, with the help of some Median nobles. [17] The war between the Persians and the Medes ended in 550 B.C. with Cyrus securing a final victory over his foe and becoming the King of Persia. [18] After the conquest of Lydia – an ancient Kingdom in western Anatolia, in what is today Turkey – and Babylon, the Achaemenid Empire became a great empire ruling a large part of Asia.

In the Cylinder, Cyrus introduces himself: “I am Cyrus, king of the universe, the great king, the powerful king, king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four quarters of the world, son of Cambyses, the great king, king of the city of Anshan, grandson of Cyrus, the great king, ki[ng of the ci]ty of Anshan, descendant of Teispes, the great king, king of the city of Anshan, the perpetual seed of kingship, whose reign Bel (Marduk) and Nabu love, and with whose kingship, to their joy, they concern themselves.”[19]

Cyrus is also one of the few venerated non-Jews in the Old Testament. The text refers to him as the Lord’s “shepherd” and “anointed”: “who says of Cyrus, ‘He is my shepherd, and he shall carry out all my purpose’; and who says of Jerusalem, ‘It shall be rebuilt’, and of the temple, ‘Your foundation shall be laid.’ Thus says the Lord to his anointed, to Cyrus, whose right hand I have grasped to subdue nations before him and strip kings of their robes, to open doors before him-and the gates shall not be closed.”[20]

Some Islamic scholars such as Abul Kalam Azad, Allamah Tabataba’i, and Morteza Motahhari believe that “Dhul-Qarnayn” in Sura Al-Kahf of the Qur’an refers to Cyrus the Great. [21] This claim is, however, controversial. The Qur’an describes Dhul-Qarnayn as a just and divinely-chosen ruler: “Verily We established his power on earth, and We gave him the ways and the means to all ends. One (such) way he followed.”[22]

Cyrus also features prominently in various historical texts. Herodotus, the great Greek historian, writes that Iranians regarded Cyrus as “The Father” because he was a gentle ruler who provided for his subjects all things good. [23] Xenophon, the Greek historian and soldier, wrote “Cyropaedia” in the early 4th century B.C. which recounts the life and beliefs of Cyrus as an ideal and tolerant ruler. He praises Cyrus: “What other man but Cyrus, after having overturned an empire, ever died with the title of The Father from the people whom he had brought under his power? For it is plain that this is a name for one that bestows, rather than for one that takes away.” [24] Cyrus’s policy of “remarkable tolerance based on respect for individual people, ethnic groups, other religions and ancient kingdoms” was revolutionary for peoples accustomed the ruthless governing styles of the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian Empires.[25]

Civic Environment

Nabonidus, the last king of the Babylonian Empire, is referred to in historical texts as a tyrant who neglected gods and religious rites.[26] According to the Cylinder his measures angered the gods of Babylon: “he brought the daily offerings to a halt; he inter[fered with the rites and] instituted […….] within the sanctuaries. In his mind, reverential fear of Marduk, king of the gods, came to an end. He did yet more evil to his city every day; … his [people …………….…], he brought ruin on them all by a yoke without relief. Enlil-of-the-gods became extremely angry at their complaints, and […] their territory.”[27] Cyrus considered himself to chosen by Marduk, the god of Babylon, to save the city: “Seeking for the upright king of his choice, he took the hand of Cyrus, king of the city of Anshan, and called him by his name, proclaiming him aloud for the kingship over all of everything.”[28]

In 597 B.C., the king of Babylon Nebuchadnezzar II invaded Judea, captured Jerusalem and sent the king of Judah along with his family, commanders, and deputies as captives to Babylon. After the appointed king of Judah rebelled against Babylon, the Babylonian king attacked Jerusalem once again in 586 B.C. [29] The story of the attack is recounted in the Old Testament: “He burned the house of the Lord, the king’s house, and all the houses of Jerusalem; every great house he burned down. All the army of the Chaldeans who were with the captain of the guard broke down the walls around Jerusalem. Nebuzaradan the captain of the guard carried into exile the rest of the people who were left in the city and the deserters who had defected to the king of Babylon—all the rest of the population. But the captain of the guard left some of the poorest people of the land to be vine-dressers and tillers of the soil.”[30] These events resulted in what is called the “Babylonian captivity.”

In 597 B.C., the king of Babylon Nebuchadnezzar II invaded Judea, captured Jerusalem and sent the king of Judah along with his family, commanders, and deputies as captives to Babylon. After the appointed king of Judah rebelled against Babylon, the Babylonian king attacked Jerusalem once again in 586 B.C. [29] The story of the attack is recounted in the Old Testament: “He burned the house of the Lord, the king’s house, and all the houses of Jerusalem; every great house he burned down. All the army of the Chaldeans who were with the captain of the guard broke down the walls around Jerusalem. Nebuzaradan the captain of the guard carried into exile the rest of the people who were left in the city and the deserters who had defected to the king of Babylon—all the rest of the population. But the captain of the guard left some of the poorest people of the land to be vine-dressers and tillers of the soil.”[30] These events resulted in what is called the “Babylonian captivity.”

The Jewish people suffered greatly during their captivity in Babylon. They were persecuted both by those in authority and the masses, particularly when they first arrived in Babylon.[31] Regardless, they preserved their religious identity and spirit as a people, and hoped to return to their homeland one day. [32]

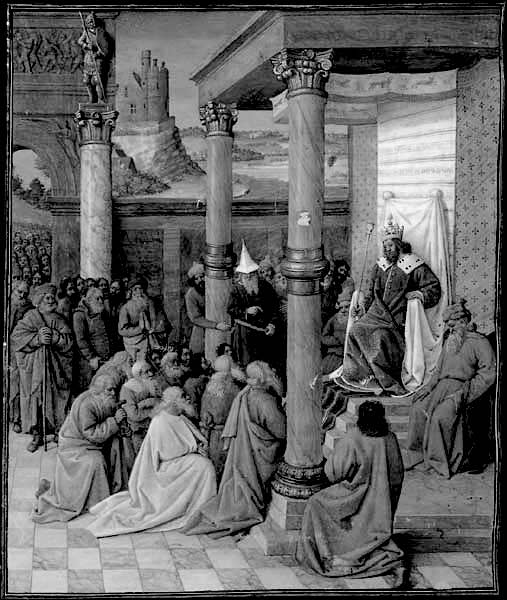

In 539 B.C., Cyrus attacked Babylon, defeated Nabonidus and placed Babylon under his rule. The Jews welcomed him as a liberator.[33] He officially declared freedom for the Jews and allowed them to return to their homeland.[34] According to Ezra, up to 50,000 Jews returned to Judea. [35]Cyrus also allowed them to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem and supported its reconstruction with the empire’s own finances.[36] Moreover, he ordered that the valuables confiscated by Nabonidus be returned to the Jewish people.[37]

Cyrus’s edict is cited in Ezra: “‘Thus says King Cyrus of Persia: The Lord, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth, and he has charged me to build him a house at Jerusalem in Judah. Any of those among you who are of his people—may their God be with them!—are now permitted to go up to Jerusalem in Judah, and rebuild the house of the Lord, the God of Israel—he is the God who is in Jerusalem; and let all survivors, in whatever place they reside, be assisted by the people of their place with silver and gold, with goods and with animals, besides freewill-offerings for the house of God in Jerusalem.’”[38]

Not all Jews in Babylon decided to return to Judea. Many of them stayed because of their personal ties and business interests in Babylon. Under Cyrus’s rule, they enjoyed the freedom of religion and worship even when they remained in Babylon. [39] Cyrus’s policy of religious tolerance was not limited to the Jewish people in his kingdom. His treatment of the Jews has attracted more attention than his treatment of other peoples due to its extensive coverage in historical and religious texts, but the Cyrus Cylinder does not mention any religions by name and declares religious freedom for all people.

Outside of his religious policies, Cyrus instated a decentralized administration in his empire. He granted limited autonomy and freedom to administrative units called satrapies, which were in turn subdivided into smaller sub-units. Each of these smaller sub-units was managed by a governor. The sub-units as well enjoyed independence and autonomy in various areas including religious affairs.[40]

Message and Audience

Cyrus the Great not only established an unprecedented political system but also presented the people under his rule with a new type of relationship with their ruler: benevolence. He is remembered as a benevolent ruler for the ways he dealt with the Babylonian and Jewish peoples.[41] Cyrus’s policy of religious tolerance, recorded in the Cyrus Cylinder, allowed deported peoples to return to their homelands and restore their sanctuaries. Although the Cylinder does not mention the Jews by name, biblical accounts confirm that the Jews were among the peoples liberated by Cyrus. Cyrus ruled a vast multi-ethnic territory and sensible statecraft dictated that he allow different nations to worship their own gods and practice their own religious rites and ceremonies. His policy of religious freedom greatly contributed to his success in founding the Achaemenid Empire.[42]

The Cylinder records Cyrus’s decision to allow deported peoples such as the Jews to return to their homeland: “Akkad, the land of Eshnunna, the city of Zamban, the city of Meturnu, Der, as far as the border of the land of Guti – the sanctuaries across the river Tigris – whose shrines had earlier become dilapidated, the gods who lived therein, and made permanent sanctuaries for them. I collected together all of their people and returned them to their settlements, and the gods of the land of Sumer and Akkad which Nabonidus – to the fury of the lord of the gods – had brought into Shuanna, at the command of Marduk, the great lord, I returned them unharmed to their cells, in the sanctuaries that make them happy.”[43]

In total, the Cyrus Cylinder contains three separate and important messages: it establishes racial, linguistic, and religious equality for all; it allows captives in Babylon to return to their homeland; and it permits returning gods to their sanctuaries as well as the reconstruction of destroyed temples.[44] In addition to the return of the Jews to Judea and the reconstruction of their Temple, the Cylinder also initiated the reconstruction of Babylonian temples, the return of local gods to their sanctuaries, and the removal of gods imposed on local populations from outside from local sanctuaries.

Outreach Activities

The Cyrus Cylinder follows a tradition that existed in Mesopotamia since before the time of Cyrus’s conquest of Babylon. Under this tradition, kings began their reign with declarations of reform.[45] The reforms of Urukagina, the ruler of Lagash, circa 2350 B.C. and the codes of Ur-Nammu and Hammurabi are other examples of this tradition. The Cylinder was found during an archaeological excavation in Babylon in Iraq in 1879, and has been kept at the British Museum ever since.[46] It is often held to be the first human rights document.[47] The Cylinder has been translated into the six official languages of the UN,[48] and the Pahlavi regime gave a replica of the Cylinder to the UN as a gift. It is on display at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City.[49]

Cyrus’s policies of tolerance, justice, and religious freedom influenced many leaders during his lifetime and thereafter. Prominent leaders such as Alexander the Great, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin drew inspiration from Cyrus’s story as recounted in the “Cyropaedia.”[50] Cambyses II, son of Cyrus the Great, followed his father’s example after gaining power and respected local gods, most notably after his conquest of Egypt. Similarly, Darius the Great used religion as a political tool to consolidate his imperial power. He respected the gods of his satrapies even though he declared himself a devotee of Ahura Mazda. Tablets written in the Elamite language found in Persepolis show that Darius allowed the followers of different religions in his territory to worship their ancestral gods and even provided them with grants from his treasury.[51] The rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem was also finished in the sixth year of the reign of King Darius with his financial support.[52]

Cyrus has also been a source of inspiration in the modern era. Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States and author of the American Declaration of Independence, and other founders of the United States adopted the progressive ideas of Cyrus the Great years before the Cyrus Cylinder was discovered. Jefferson had two copies of the “Cyropaedia,” and it influenced him to such an extent that he advised his grandson to read it; [53] this shows how important Cyrus’s example was to the writers of the US Constitution. According to John Curtis, the British Museum exhibition curator, “[t]he Cyrus Cylinder and associated objects represent a new beginning for the Ancient Near East… [t]he idea of freedom of religion appealed to the founders of the United States, which was originally colonized, in part, by Europeans escaping religious persecution”[54]

Even today Cyrus the Great is considered to be one of the most influential leaders in history. In 1992, he was ranked 87 in “The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History,” a book was written by Michael H. Hart, a Jewish American astrophysicist and author.[55] Shirin Ebadi, while accepting her Noble Peace Prize on December 10, 2003, stated: “I am an Iranian. A descendant of Cyrus the Great. The very emperor who proclaimed at the pinnacle of his power 2500 years ago that… ‘he would not reign over the people if they did not wish it.’ And [he] promised not to force any person to change his religion or faith and guaranteed freedom for all. The Charter of Cyrus the Great is one of the most important documents in the history of human rights.”[56]

Learn More

Wikipedia

Babylonian Captivity. Wikipedia. EN.

Babylonian Captivity. Wikipedia. FA.

Babylonian Captivity. Wikipedia. AR.

Cyrus the Great. Wikipedia. EN.

Cyrus the Great. Wikipedia. FA.

Cyrus the Great. Wikipedia. AR.

Articles & Documents

«ترجمه متن استوانه کوروش بزرگ»، ترجمه دکتر شاهرخ رزمجو، موزه بریتانیا، پاراگراف 26-24. http://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/cyrus-cylinder_translation-persian.pdf.

دریایی، تورج، «کوروش بزرگ پادشاه باستانی ایران»، ترجمه آذردخت جلیلیان، وبسایت تورج دریایی، صص 22 و 24. http://www.tourajdaryaee.com/wp-content/uploads/Daryaee-Cyrus-Persian.pdf.

“The Cyrus Cylinder: Placing Law Over a Barrel.” HARRIS & GREENWELL. http://www.harris-greenwell.com/uploads/HGS/Cyruscylinder.pdf.

“The Cyrus Cylinder”. FEZANA Journal. 4 July 2013. http://cyruscylinder2013.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/FEZANA_Journal_2013_Summer.pdf.

Netzer, Amnon. “Some Notes on the Characterization of Cyrus the Great in Jewish and Judeo-Persian Writings”. The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies. http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/PDF/cyrus_charecterization_judeo-persian.pdf.

Van Der Spek, R. J. “Cyrus the Great, Exiles and Foreign Gods: A Comparison of Assyrian and Persian Policies on Subject Nations”. Published in Wouter Henkelman, Charles Jones, Michael Kozuh and Christopher Woods (eds.), Extraction and Control: Studies in Honor of Matthew W. Stolper. Oriental Institute Publications. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. 2014. http://dare.ubvu.vu.nl/bitstream/handle/1871/50835/Stolper_FS_22_VdSpek_Cyrus.pdf?sequence=1.

News & Analysis

«اسرائیل: آشنایی با «حضرت کوروش منجی یهودیان»، ایرانوایر، 29 سپتامبر 2013. http://iranwire.com/blogs/6264/2867/.

«چرا کوروش کبير ذوالقرنين است؟»، عصر ایران، 25 فروردین 1390. http://bit.ly/1wBpTmF.

«سرگذشت یهودیان ایران – نمایشگاهی در تل آویو»، دویچه وله فارسی، 20 ژانویه 2011. http://dw.de/p/QtJX.

ترهون، لیا، «جفرسن و دموکراسی ایالات متحده از فرمانروای ایران باستان تأثیر پذیرفتند»، IIP Digital ، وزارت امورخارجه ایالات متحده، 13 مارس 2013. http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/persian/article/2013/03/20130313144082.html#axzz3Q2c9FZIE.

“Cyrus Cylinder.” British Museum Website. http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/me/c/cyrus_cylinder.aspx.

“Cyrus the Great”. New World Encyclopedia. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Cyrus_the_Great#cite_note-15.

“The British Museum lends the Cyrus Cylinder to the National Museum of Iran.” British Museum Website. 10 Sep. 2010. http://www.britishmuseum.org/about_us/news_and_press/statements/cyrus_cylinder.aspx.

“Babylonian Exile”. Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 Nov. 2014. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/47693/Babylonian-Exile.

“Cyrus Cylinder: How a Persian Monarch Inspired Jefferson”. BBC News. 11 Mar. 2013. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-21747567.

“CYRUS iii. Cyrus II The Great”. Encyclopædia Iranica. 10 Nov. 2011. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/cyrus-iii.

“History of Iran: Cyrus The Great”, Iran Chamber Society. http://www.iranchamber.com/history/cyrus/cyrus.php.

Chiacu, Doina. “Cyrus Cylinder, Ancient Decree of Religious Freedom, Starts U.S. Tour”. Reuters. 7 Mar. 2013. http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/03/07/us-usa-cyrus-idUSBRE9260Y820130307.

Ebadi. Shirin. “Nobel Lecture”. Nobelpriz.org. 10 Dec. 2003. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2003/ebadi-lecture-e.html.

Eduljee, K. E. “Cyrus the Great Liberator”. Heritage Institute. http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/achaemenian/cyrus.htm.

Ferguson, Barbara G.B. “The Cyrus Cylinder—Often Referred to as The “First Bill of Human Rights”.” Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. May 2013. http://www.wrmea.org/2013-may/the-cyrus-cylinder%E2%80%94often-referred-to-as-the-first-bill-of-human-rights.html.

Frye, Richard N. “Cyrus II | Biography – King of Persia”. Encyclopedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/148758/Cyrus-II.

Ghasemi, Shapour. “History of Iran: The Cyrus the Great Cylinder”. Iran Chamber Society. http://www.iranchamber.com/history/cyrus/cyrus_charter.php.

Hassani, Behzad. “Human Rights and Rise of the Achaemenid Empire: Forgotten Lessons from a Forgotten Era”. The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies. June 2007. http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/History/hakhamaneshian/human_rights.htm.

Horne, Charles F. “History of Iran: The Kurash Prism Cyrus the Great; The decree of return for the Jews, 539 BCE”. Iran Chamber Society. http://www.iranchamber.com/history/cyrus/cyrus_decree_jews.php.

Largest empire by percentage of world population. Guinness World Records. http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/largest-empire-by-percentage-of-world-population.

Price, Roger. “What if Cyrus had not freed the Jews?”. Jewish Journal. 24 Sep. 2013. http://www.jewishjournal.com/judaismandscience/item/what_if_cyrus_had_not_freed_the_jews.

Stephan, Annelisa. “Why the Cyrus Cylinder Matters Today”. The Getty Iris. 3 Oct. 2013. http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/why-the-cyrus-cylinder-matters-today.

The First Global Statement of The Inherent Dignity and Equality of All, United Nations, 10 Dec. 2008. http://www.un.org/en/events/humanrightsday/2008/history.shtml.

Books

عهد عتیق، کتاب اشعیا، مرکز پژوهشهای مسیحی. http://www.farsicrc.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=153&Itemid=170.

عهد عتیق، کتاب دوم پادشاهان، مرکز پژوهشهای مسیحی. http://www.farsicrc.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=142&Itemid=159.

عهد عتیق، کتاب عزرا، مرکز پژوهشهای مسیحی. http://www.farsicrc.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=145&Itemid=162.

قرآن، ترجمه مهدی محییالدین الهی قمشهای، سوره کهف.

گزنفون، کوروش نامه، ترجمه رضا مشایخی، تریبون زمانه. https://www.tribunezamaneh.com/archives/24942.

هرودوت، تاریخ هردوت، ترجمه غ. وحید مازندرانی، تهران: مرکز انتشارات علمی و فرهنگی، 1362.

Abbott, Jacob. Cyrus the Great. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1900. Print.

Aharoni, Yohanan. The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1979. Print.

Boardman, John. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 10: Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean, C. 525 to 479 B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988. Print.

Boyce, Mary. Zoroastrians, Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979. Print.

Briant, Pierre. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002. Print.

Dandamaev, M. A. A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1989. Print.

Farrokh, Kaveh. Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. Oxford, U.K.: Osprey, 2007. Print.

Finkel, Irving. The Cyrus Cylinder: The King of Persia’s Proclamation from Ancient Babylon. London: I. B. Taurus, 2013. Print.

Forbes, Steve, and John Prevas. Power Ambition Glory: The Stunning Parallels between Great Leaders of the Ancient World and Today — and the Lessons You Can Learn. New York: Crown Business, 2009. Print.

Herodotus. The History of Herodotus. Trans. G. C. Macaulay. McLean, VA: IndyPublish.com, 2002. Print.

Pasachoff, Naomi E., and Robert J. Littman. A Concise History of the Jewish People. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005. Print.

Slatyer, William. Life/death Rhythms of Ancient Empires – Climatic Cycles Influence Rule of Dynasties: A Predictable Pattern of Religion, War, Prosperity and Debt. PartridgeIndia, 2014. Print.

The Captivity of the Jews: And Their Return from Babylon. London: Religious Tract Society, 1840. Print.

Xenophon, and Larry Hedrick. Xenophon’s Cyrus the Great: The Arts of Leadership and War. New York: Truman Talley /Saint Martin’s, 2006. Print.

Multimedia

«اهمیت و نقش آزادیهای مذهبی در موفقیت سیاسی کوروش کبیر»، بی بی سی فارسی، 27 اوت 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/persian/iran/2013/08/130827_l93_cyrus_book.

«نیل مک گرگور: 2600 سال تاریخ در یک شی»، تد، ژوئیه 2011، http://www.ted.com/talks/neil_macgregor_2600_years_of_history_in_one_object?language=fa.

Footnotes

[1] Xenophon, and Larry Hedrick. Xenophon’s Cyrus the Great: The Arts of Leadership and War. New York: Truman Talley /Saint Martin’s, 2006. p.119. Print.

[2] Ferguson, Barbara G.B. “The Cyrus Cylinder-Often Referred to as The “First Bill of Human Rights”.” Washington Report on Middle East Affairs. May 2013. http://www.wrmea.org/2013-may/the-cyrus-cylinder%E2%80%94often-referred-to-as-the-first-bill-of-human-rights.html.

[3] Largest empire by percentage of world population. Guinness World Records. http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/largest-empire-by-percentage-of-world-population.

[4] Barbara G.B. Ferguson. Ibid.

[5] Forbes, Steve, and John Prevas. Power Ambition Glory: The Stunning Parallels between Great Leaders of the Ancient World and Today — and the Lessons You Can Learn. New York: Crown Business, 2009. p.34. Print.

[6] «اسرائیل: آشنایی با «حضرت کوروش منجی یهودیان»»، ایرانوایر، 29 سپتامبر 2013. http://iranwire.com/blogs/6264/2867/.

[7] “The Cyrus Cylinder: Placing Law Over a Barrel.” HARRIS & GREENWELL. http://www.harris-greenwell.com/uploads/HGS/Cyruscylinder.pdf.

[8] Frye, Richard N. “Cyrus II | Biography – King of Persia.” Encyclopedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/148758/Cyrus-II.

[9] “History of Iran: Cyrus The Great”. Iran Chamber Society. http://www.iranchamber.com/history/cyrus/cyrus.php.

[10] دریایی، تورج، «کوروش بزرگ پادشاه باستانی ایران»، ترجمه آذردخت جلیلیان، وبسایت تورج دریایی، صص 22 و 24. http://www.tourajdaryaee.com/wp-content/uploads/Daryaee-Cyrus-Persian.pdf.

[11] “Translation of the text on the Cyrus Cylinder”. Translation by Irving Finkel. The British Museum. para. 24-26. http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/articles/c/cyrus_cylinder_-_translation.aspx.

[12] دریایی، پیشین، صص 21 و 22.

[13] Hassani, Behzad. “Human Rights and Rise of the Achaemenid Empire: Forgotten Lessons from a Forgotten Era”. The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies. June 2007. http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/History/hakhamaneshian/human_rights.htm.

[14] Briant, Pierre. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002. 79. Print.

[15] تورج دریایی، پیشین، ص 24.

[16] Abbott, Jacob. Cyrus the Great. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1900. p.222. Print.

[17] ر.ک. هرودوت، تاریخ هردوت، ترجمه غ. وحید مازندرانی، تهران: مرکز انتشارات علمی و فرهنگی، 1362، صص 103-97.

[18] Dandamaev, M. A. A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1989. Print.

[19] “Translation of the text on the Cyrus Cylinder”. op.cit. para. 20-22.

[20] Old Testament. Isaiah. 44: 28 – 45: 1. http://bible.oremus.org/?passage=Isaiah.

[21] «چرا کوروش کبير ذوالقرنين است؟»، عصر ایران، 25 فروردین 1390. http://bit.ly/1wBpTmF.

[22] The Qur’an. Translation by Abdullah Yusuf Ali. 18:84-85.

[23] Herodotus. The History of Herodotus. Trans. G. C. Macaulay. McLean, VA: IndyPublish.com, 2002. 3.89. Print.

[24] Xenophon. The Cyropaedia: Or, Institution of Cyrus, and the Hellenics, Or Grecian History. Trans. J. S. Watson and Henry Dale. London: H.G. Bohn, 1855. Book VII. 2.7. Internet.

[25] Boardman, John. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 10 : Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean, C. 525 to 479 B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988. 42. Print.

[26] تورج دریایی، پیشین، ص 22.

[27] “Translation of the text on the Cyrus Cylinder”. op.cit. para. 7-9.

[28] Ibid. para. 12.

[29] Pasachoff, Naomi E., and Robert J. Littman. A Concise History of the Jewish People. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005. 43. Print.

[30] Old Testament. 2 Kings. 25: 9-12. http://bible.oremus.org/?passage=2Kings.

[31] The Captivity of the Jews: And Their Return from Babylon. London: Religious Tract Society, 1840. 74. Print.

[32] “Babylonian Exile”. Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 November 2014. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/47693/Babylonian-Exile.

[33] “History of Iran: Cyrus The Great”, op.cit.

[34] Farrokh, Kaveh. Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. Oxford, U.K.: Osprey, 2007. 45. Print.

[35] Old Testament. Ezra. 2: 64-65. http://bible.oremus.org/?passage=Ezra.

[36] Farrokh. op.cit. 45.

[37] Ezra. op.cit. 1:7.

[38] Ibid., 1: 2-4.

[39] Farrokh. op.cit. 45.

[40] Aharoni, Yohanan. The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1979. 411. Print.

[41] دریایی، پیشین، ص 22.

[42] «اهمیت و نقش آزادیهای مذهبی در موفقیت سیاسی کوروش کبیر»، بی بی سی فارسی، 27 اوت 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/persian/iran/2013/08/130827_l93_cyrus_book.

[43] “Translation of the text on the Cyrus Cylinder”. op.cit. para. 31-34.

[44] Farrokh. op.cit. 44.

[45] “Cyrus Cylinder”. British Museum Website. http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/me/c/cyrus_cylinder.aspx.

[46] “The British Museum lends the Cyrus Cylinder to the National Museum of Iran”. British Museum Website. 10 Sep. 2010. 2015. http://www.britishmuseum.org/about_us/news_and_press/statements/cyrus_cylinder.aspx.

[47] The First Global Statement of The Inherent Dignity and Equality of All, United Nations, 10 Dec. 2008. http://www.un.org/en/events/humanrightsday/2008/history.shtml.

[48] Ghasemi, Shapour. “History of Iran: The Cyrus the Great Cylinder”. Iran Chamber Society. http://www.iranchamber.com/history/cyrus/cyrus_charter.php.

[49] Finkel, Irving. The Cyrus Cylinder: The King of Persia’s Proclamation from Ancient Babylon. London: I. B. Taurus, 2013. 82. Print.; “The Cyrus Cylinder”. FEZANA Journal. 4 July 2013. 62. Internet. http://cyruscylinder2013.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/FEZANA_Journal_2013_Summer.pdf.

[50] Chiacu, Doina. “Cyrus Cylinder, Ancient Decree of Religious Freedom, Starts U.S. Tour”. Reuters. 7 Mar. 2013. http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/03/07/us-usa-cyrus-idUSBRE9260Y820130307.

[51] Boyce, Mary. Zoroastrians, Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979. 56. Print.

[52] Ezra. op.cit. 6: 1-15.

[53] Lea Terhune. “Ancient Persian Ruler Influenced Thomas Jefferson, U.S. Democracy”. IIP Digital. 13 March 2013. http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/article/2013/03/20130312143982.html#axzz3Wpu2oEDY.

[54] Ibid.

[55] “Cyrus the Great”. New World Encyclopedia. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Cyrus_the_Great.

[56] Ebadi. Shirin. “Nobel Lecture”. Nobelpriz.org. 10 Dec. 2003. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2003/ebadi-lecture-e.html.