Vision and Motivation

By the second half of the 1980s, the political atmosphere in the Soviet Union and its satellite states was more relaxed than it had been in previous decades, due to Mikhail Gorbachev’s introduction of two new governmental policies: Glasnost, a government effort to make the country’s governance transparent and open to debate, and Perestroika, the restructuring of the Soviet political and economic system. Many historians cite the introduction of these two policies as a catalyst for many of the nonviolent democratic revolutions that erupted in Soviet-bloc countries.[1]

By the second half of the 1980s, the political atmosphere in the Soviet Union and its satellite states was more relaxed than it had been in previous decades, due to Mikhail Gorbachev’s introduction of two new governmental policies: Glasnost, a government effort to make the country’s governance transparent and open to debate, and Perestroika, the restructuring of the Soviet political and economic system. Many historians cite the introduction of these two policies as a catalyst for many of the nonviolent democratic revolutions that erupted in Soviet-bloc countries.[1]

Czechoslovakia’s Communist Party took efforts to prevent Gorbachev’s reforms from being enacted at home, where an autocratic political system prevailed, government dissent was not tolerated, and political activists were punished harshly through the second half of the 1980s.[2] Through purges of suspected dissidents and their family members, the Communist government established tight control over its citizens. The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia continued to carry out these policies in the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent democratic transition of other Soviet-bloc countries such as Poland and Hungary. These politically repressive conditions, combined with the collapse of the Soviet Union, inspired the Czechoslovaks to demand change from their government. In the last six weeks of 1989, opposition activists staged what became known as the “Velvet Revolution,” to overthrow the Communist government in Czechoslovakia.

Velvet is associated with Czechoslovakia’s democratic revolution because it was a peaceful movement ending in compromise, not violence; Havel and his activist movement had a strategic preference for nonviolent action that facilitated the movement’s success. While Slovak members of the activist movement referred to the democratic transition as the Gentle Revolution, Havel and his Czech compatriots continue to refer to it as the Velvet Revolution. Some argue that Lou Reed’s Velvet Underground catalyzed the adoption of velvet by Czech civic activists, after a rare copy of the band’s first record was snuck into Prague in 1968. The Velvet Underground later influenced The Plastic People of the Universe, close friends of Vaclav Havel who were an underground rock band that musically embodied Czech’s opposition movement from 1968 to 1989.[3]

Goals and Objectives

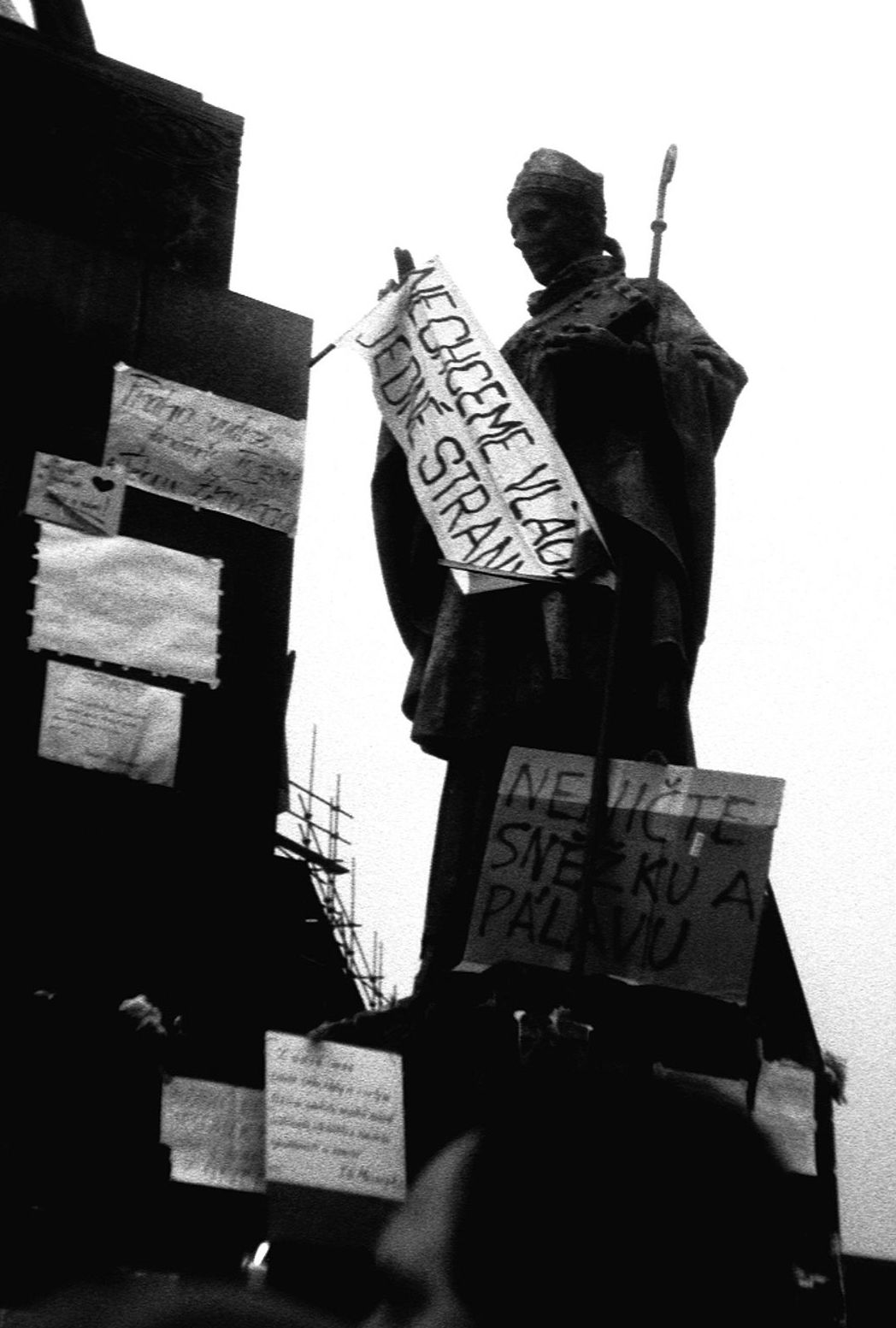

The Velvet Revolution began somewhat spontaneously on November 17, 1989, with a student march organized to mark the 50th anniversary of a protestor’s death in a student demonstration against the Nazi occupation. However, it quickly turned into an anti-government protest, with students carrying banners and chanting anti-Communist slogans.[4] Although the student protest was conducted in a peaceful manner, 167 student protestors were hospitalized after being beaten by police.[5] The demonstration and its accompanying violence inspired workers’ unions and other civic groups to organize for a free and democratic Czechoslovakia.[6]

The Velvet Revolution began somewhat spontaneously on November 17, 1989, with a student march organized to mark the 50th anniversary of a protestor’s death in a student demonstration against the Nazi occupation. However, it quickly turned into an anti-government protest, with students carrying banners and chanting anti-Communist slogans.[4] Although the student protest was conducted in a peaceful manner, 167 student protestors were hospitalized after being beaten by police.[5] The demonstration and its accompanying violence inspired workers’ unions and other civic groups to organize for a free and democratic Czechoslovakia.[6]

Following the student demonstration, mass protests were held in several cities across Czechoslovakia. Actors and playwrights were prominent within the dissident movement, so theaters became meeting places where activists devised their political strategies and held public discussions.[7] During a discussion held in a Prague theatre on November 19, a group called the Civic Forum was established as a collection of spokespeople of the democratic movement.[8] The group demanded “the resignation of the Communist government, the release of prisoners of conscience, and investigations into the November 17 police action.”[9]

Leadership

The Civic Forum, the heart of Czechoslovakia’s democratic movement, was led by Vaclav Havel. Havel, an author, playwright, and poet, used his talent to craft the movement’s messaging, challenging the government in a way that captured the public’s confidence and imagination. “I really do inhabit a system in which words are capable of shaking the entire structure of government, where words can prove mightier than ten military divisions,” Havel has said.[10] In plays like The Garden Party, The Memorandum, and The Interview, Havel showed the effects of a repressive government bureaucracy on ordinary people and their private lives and relations.[11] He had been active during the “Prague Spring” period of liberalization in Czechoslovakia in 1968, when the country’s leader, Alexander Dubček, lifted restrictions on freedom of speech and state controls on industry. For a few months, Czechoslovaks were able to openly criticize Soviet rule, travel about the country more freely, and form new political clubs not affiliated with the Communist Party. However, that summer Soviet troops were sent into the country to stop the reforms, causing Havel to speak out against the invasion on Radio Free Czechoslovakia. As a result of his human rights activism, his plays were banned from Czechoslovak theaters, and in 1977, he was sentenced to four and a half years of hard labor.[12]

The Civic Forum, the heart of Czechoslovakia’s democratic movement, was led by Vaclav Havel. Havel, an author, playwright, and poet, used his talent to craft the movement’s messaging, challenging the government in a way that captured the public’s confidence and imagination. “I really do inhabit a system in which words are capable of shaking the entire structure of government, where words can prove mightier than ten military divisions,” Havel has said.[10] In plays like The Garden Party, The Memorandum, and The Interview, Havel showed the effects of a repressive government bureaucracy on ordinary people and their private lives and relations.[11] He had been active during the “Prague Spring” period of liberalization in Czechoslovakia in 1968, when the country’s leader, Alexander Dubček, lifted restrictions on freedom of speech and state controls on industry. For a few months, Czechoslovaks were able to openly criticize Soviet rule, travel about the country more freely, and form new political clubs not affiliated with the Communist Party. However, that summer Soviet troops were sent into the country to stop the reforms, causing Havel to speak out against the invasion on Radio Free Czechoslovakia. As a result of his human rights activism, his plays were banned from Czechoslovak theaters, and in 1977, he was sentenced to four and a half years of hard labor.[12]

A strong believer in both liberal democracy and non-violent protest, Havel was also known as one of the founders of Charter 77, a civic initiative created in 1977. This group wrote a manifesto calling on the regime to live up to its international human rights commitments; this prompted the government to imprison its members and ban the Charter 77 document. On November 19, 1989, Havel founded the Civic Forum.[13] Under his leadership, prominent members of Charter 77 came together with other dissident groups to form the Civic Forum, which was intended to unite the Czechoslovak opposition in order to overthrow the Communist regime. Successfully having orchestrated a series of public demonstrations and strikes over the next three weeks, Havel became the face of the Czech opposition and led the group in talks with the government in early December 1989.

After successful negotiations with the Communist government, Havel was appointed president of Czechoslovakia in 1989, and then elected president in June 1990, holding the office until 2003. For his civic activism and political leadership he has received numerous awards including Liberal International’s Prize for Freedom, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Philadelphia Medal, the Order of Canada and the International Gandhi Prize. In addition to innumerable awards and distinctions, Havel has become an inspiration to democratic movements across the globe.

Civic Environment

Under the Communist regime, Czechoslovakians were offered little space to express political dissent. The Communist Party successfully persecuted political dissidents before the Velvet Revolution, most notoriously after the Prague Spring of 1968, when hundreds of thousands of Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia to put an end to political reforms and strengthen the Party’s authority. Even small signs of non-conformity were taken seriously; one man recalls that his grandfather, a university lecturer, was reported to the authorities for referring to his students as “ladies and gentlemen” rather than “comrades.”[14]

Under the Communist regime, Czechoslovakians were offered little space to express political dissent. The Communist Party successfully persecuted political dissidents before the Velvet Revolution, most notoriously after the Prague Spring of 1968, when hundreds of thousands of Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia to put an end to political reforms and strengthen the Party’s authority. Even small signs of non-conformity were taken seriously; one man recalls that his grandfather, a university lecturer, was reported to the authorities for referring to his students as “ladies and gentlemen” rather than “comrades.”[14]

The regime’s attempts to place restrictions on free speech, which had been used against Czech opposition groups in the past, failed to muzzle the zeal of Havel and the Civic Forum. During the initial November 17 nonviolent protest, student activists offering flowers to police were brutally beaten; however, the subsequent marches, protests, and strikes that took place in the following week could not be silenced by police brutality. The barrage of nonviolent activism had such a profound effect on the Czechoslovak people, including police and members of internal security institutions, that protests and strikes increasingly grew larger and faced less government repression. Nonviolent protestors led by Havel and the Civic Forum catalyzed a significant shift in the civic environment of Czechoslovakia.

Message and Audience

During the first opposition protest of the Velvet Revolution on November 17, student organizers directed their message demanding the government’s resignation to both the Czechoslovak people and the government via banners and posters. With the formation of the Civic Forum less than 48 hours later, most university students, theatre employees and actors went on strike instantaneously, yet Havel knew that many more would have to join them in strike in order for the movement to grow and bear fruit. Havel and his cohort agreed to continue pushing for the government to resign; however, in order to bolster national support for his movement, a new message needed to be crafted for the Czech people. Havel, who determined that methods of economic and social noncooperation in the form of strikes would be most effective against the government, sought to organize a general strike for November 27 that would span across Czechoslovakia.

During the first opposition protest of the Velvet Revolution on November 17, student organizers directed their message demanding the government’s resignation to both the Czechoslovak people and the government via banners and posters. With the formation of the Civic Forum less than 48 hours later, most university students, theatre employees and actors went on strike instantaneously, yet Havel knew that many more would have to join them in strike in order for the movement to grow and bear fruit. Havel and his cohort agreed to continue pushing for the government to resign; however, in order to bolster national support for his movement, a new message needed to be crafted for the Czech people. Havel, who determined that methods of economic and social noncooperation in the form of strikes would be most effective against the government, sought to organize a general strike for November 27 that would span across Czechoslovakia.

During the next several days, Havel and the Civic Forum coordinated mass demonstrations throughout the country, using the platform both to openly express its displeasure with the government and to spread word about the November 27 general strike. Together, tens of thousands gathered in protest, chanting in the streets, “It’s finally happening!”[15] The democratic movement in Czechoslovakia built a broad base of democratic consciousness; the demonstrations in Prague on November 25 and 26 drew an estimated crowd of nearly 750,000 people.[16] The daily protests gave way to meetings between the Civic Forum and Prime Minister Ladislav Adamec, in which the Prime Minister personally guaranteed that no violence would be used against Czech citizens.[17]

Then, on November 27, a reported 75% of the Czech population participated in a two-hour general strike, showing the mass support that had gathered behind the Civic Forum. The strike, which bolstered the demands put forth by the opposition movement, ended the “popular” phase of the Velvet Revolution as Havel and the Civic Forum successfully showed the Communist regime that the Czech people would no longer obey.

Outreach Activities

Discredited and powerless against the demands of protestors, the Communist Party was pushed into talking with Havel and the Civic Forum, ushering in a new political climate. The Communist Party officially ceded its monopoly on political power in Czechoslovakia to allow for multi-party rule on November 28, just one day after the citizens’ general strike. On December 10, Communist President Gustav Husak resigned, and on December 29, the Czech Parliament appointed Vaclav Havel to the presidency of a free Czechoslovakia. As the last president of Czechoslovakia and the first of the Czech Republic, Havel helped facilitate the state’s historic transition to democracy, marked by free and fair elections in June 1990, the first since 1946. The new government liberalized Czechoslovak law with respect to both politics and the economy, creating an open and free society.

Discredited and powerless against the demands of protestors, the Communist Party was pushed into talking with Havel and the Civic Forum, ushering in a new political climate. The Communist Party officially ceded its monopoly on political power in Czechoslovakia to allow for multi-party rule on November 28, just one day after the citizens’ general strike. On December 10, Communist President Gustav Husak resigned, and on December 29, the Czech Parliament appointed Vaclav Havel to the presidency of a free Czechoslovakia. As the last president of Czechoslovakia and the first of the Czech Republic, Havel helped facilitate the state’s historic transition to democracy, marked by free and fair elections in June 1990, the first since 1946. The new government liberalized Czechoslovak law with respect to both politics and the economy, creating an open and free society.

Learn More

News & Analysis

Apple, R. W. Jr. “Clamor in the East: Millions of Czechoslovaks Increase Pressure on Party with Two-Hour General Strike.” The New York Times 28 Nov 1989: A1.

“Czech Republic (2009).” Freedom House. 2009.

Esfandiari, Golnaz. “Vaclav Havel Urges Iran Student Leaders Not to Lose Hope.” Persian Letters. 11 March 2010.

Etzler, Tomas. “Disarming the Velvet Revolution.” CNN. 18 Nov 2009.

Glasser, Susan. “The FP Interview: Vaclav Havel.” Foreign Policy. 9 Dec 2009.

“Havel Expresses Solidarity With Iranian Demonstrators.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 15 June 2009.

“History Online: The “Velvet Revolution.”” Radio Prague. 1997.

Libresco, Andrea S and Jeannette Blantic. “Peace Lessons from Around the World.” 2006. PDF.

Michnik, Adam. “After the Velvet, another Velvet Revolution?” Salon.com. 20 Nov 2008.

“Panic! On the Streets of Prague.” Prague Life. 12 Feb 2010.

“Profile of Vaclav Havel.” Answers. 12 Feb. 2010.

“Vaclav Havel.” Wikipedia. 29 Jan 2010.

“Velvet Revolution.” Wikipedia. 9 Feb 2010.

Video

“The Power of the Powerless.” YouTube. 22 April 2009.

“The Velvet Revolution.” Columbia University. 2006.

Books

Keane, John (ed). The Power of the Powerless. New York: ME Sharpe, Inc. 1990.

Kukral, Michael Andrew. Prague 1989: Theater of Revolution. New York: Columbia University Press. 1997.

Wheaton, Bernard and Zdenek Kavan. The Velvet Revolution: Czechoslovakia 1988-1991. Colorado: Westview Press, 1992.

Footnotes

[1] “Panic! On the Streets of Prague.” Prague Life. 12 Feb 2010.

[2] Wheaton, Bernard and Zdenek Kavan. The Velvet Revolution: Czechoslovakia 1988-1991. Colorado: Westview Press, 1992.

[3] Ash, Timothy Garton. “Velvet Revolution: The Prospects.” New York Review of Books. 3 Dec 2009.

[4] “History Online: The ‘Velvet Revolution.'” Radio Prague. 1997.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Wheaton and Kavan.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “History Online: The ‘Velvet Revolution.'”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Libresco, Andrea S and Balantic, Jeannette. “Peace Lessons from Around the World.” 2006. PDF.

[11] Lukes, Steven. “Introduction.” The Power of the Powerless. Ed. John Keane. New York: ME Sharpe, Inc, 1990. 11-22. 12.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “History Online: The ‘Velvet Revolution.'”

[14] Etzler, Tomas. “Disarming the Velvet Revolution.” CNN. 18 Nov 2009.

[15] “Panic! On the Streets of Prague.”

[16] Ibid.; Apple, R. W. Jr. “Clamor in the East: Millions of Czechoslovaks Increase Pressure on Party with Two-Hour General Strike.” New York Times November 28, 1989: A1.

[17] “History Online: The ‘Velvet Revolution.'”