Vision and Motivation

In the aftermath of World War II, the Soviet Union installed Communist puppet regimes in the Central and Eastern European states that it had occupied during the war. By installing pro-Moscow politicians as leaders of these oppressive satellite states, the Soviet Union established regional hegemony that has been commonly referred to as the Iron Curtain.[1]

In Poland, the Communist leadership arrested, executed, and exiled Polish anti-Soviet political dissidents in order to consolidate political power. By the time Poland instated its new Soviet-inspired constitution in 1952, Poles had witnessed the abolition of their Senate, rigged elections, Communist land reforms, and their country’s social and political introduction into the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union.[2]

Despite the government’s modernization efforts and introduction of socialist economic reforms in the 1980’s, its repression of its citizens’ basic human rights catalyzed the eventual fall of the Soviet-backed regime in 1989.

Goals and Objectives

The opposition movement was comprised of a diverse group of political activists including Pope John Paul II and the Catholic Church, Lech Walesa’s Solidarity movement, and the Orange Alternative Movement. While some of their goals varied, they shared a vision of a free, democratic Poland.

In 1978, the movement for a free Poland gained early traction with the election of Karol Józef Wojtyła, better known as Pope John Paul II, to the Papacy. The Pope was motivated by a belief that Catholicism and the individual conscience stood diametrically opposed to Communism’s suppression of religious, economic and political freedoms, which established the state as an alternative to a higher being.[3] He saw Christianity as an inseparable part of Poland’s rich cultural history, and sought to re-establish a society where Poles could freely embrace their national and religious identity.[4]

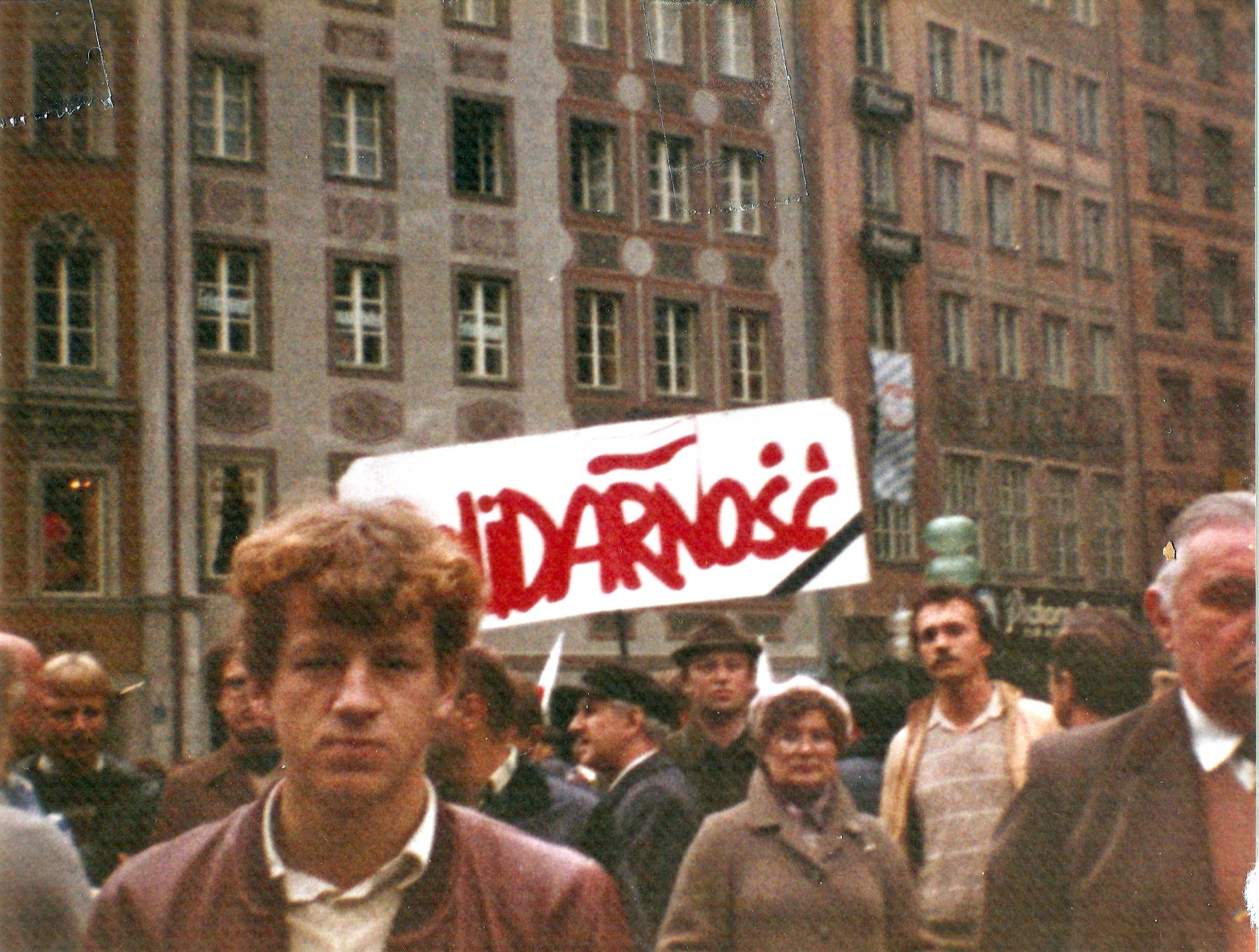

Fourteen months later the Solidarity movement would emerge, uniting many workers and intellectuals in pursuit of the aspirations articulated by the Pope. The Solidarity movement spawned from a labor strike in August 1980, when workers shut down the Gdansk shipyard over new limits on wages.[5] After successful negotiations with the government, the strike leaders formed Solidarity on September 17, 1980, making it the first independent labor union behind the Iron Curtain. Yet Solidarity was not simply a trade union; it was a social and political movement that strove for human dignity and full citizenship, rights and freedoms for all Poles.[6]

At the core of its vision was the concept of a “Self-Governing Republic,” Samorzanda Rzeczpospolita, which advocated the development of democratic institutions. Solidarity’s goal, established in the 1981 Congress, was “to create dignified conditions of life in an economically and politically sovereign Poland. By this we mean a life free from poverty, exploitation, fear and lies, in a democratically and legally organized society.” Moreover, stated the Solidarity program, “What we had in mind were not only bread, butter and sausage but also justice, democracy, truth, legality, human dignity, freedom of convictions, and the repair of the republic.”[7] These values would be the founding principles of the post-Communist Third Republic of Poland and Walesa’s presidency beginning in 1990.

Motivated by the same vision that led to the creation of Solidarity and the Pope’s desire to end Communism in Poland, the Orange Alternative, an artistic movement that engaged Polish university students, had a more abstract and aesthetic approach based on the power of imagination. “Imagination makes the world without limits…There is no single force in human life which could restrain the uncontrolled worlds of imagination. It transcends everything without using any real force; our imagination lives in us as long as it is free.”[8] With a focus on personal and collective freedom of expression as exercised through visual art, the Orange Alternative’s goal was to undermine the Communist regime’s control of consciousness through free and spontaneously subversive artistic expression. Initially, Orange Alternative participants looked for spots on city walls where the regime had painted over anti-Communist graffiti, in order to paint humorous images of dwarves on these spots. They could not be arrested by the police for opposition to the Communist regime without the authorities becoming a laughingstock over their alarm at painted dwarves on city streets.

Motivated by the same vision that led to the creation of Solidarity and the Pope’s desire to end Communism in Poland, the Orange Alternative, an artistic movement that engaged Polish university students, had a more abstract and aesthetic approach based on the power of imagination. “Imagination makes the world without limits…There is no single force in human life which could restrain the uncontrolled worlds of imagination. It transcends everything without using any real force; our imagination lives in us as long as it is free.”[8] With a focus on personal and collective freedom of expression as exercised through visual art, the Orange Alternative’s goal was to undermine the Communist regime’s control of consciousness through free and spontaneously subversive artistic expression. Initially, Orange Alternative participants looked for spots on city walls where the regime had painted over anti-Communist graffiti, in order to paint humorous images of dwarves on these spots. They could not be arrested by the police for opposition to the Communist regime without the authorities becoming a laughingstock over their alarm at painted dwarves on city streets.

Leadership

Though mass citizen participation was vital to the success of the anti-Communist movement in Poland, a democratic transition could not have happened without the leadership of people like Lech Walesa, founder of Solidarity; Pope John Paul II, head of the Catholic Church; and the founder of the Orange Alternative, Colonel Waldemar Fydrych, who was generally known by his satiric nickname “Major.” While each person had his own life history and style of leadership, they shared a deeply personal commitment to the cause: an open Polish society.

Lech Walesa’s name is synonymous with Solidarity; “He became more than just a symbol of what had been accomplished, he became the very embodiment of Solidarity.”[9] Walesa’s ability to earn the trust of the people ensured that they never lost faith, regardless of how severe the backlash from the regime was. In a letter to Walesa, one Solidarity member highlights the reason for his admiration of the movement’s leader: “You have shown us that we mustn’t be frightened off by police truncheons, nor by ridicule, nor lack of faith. The other thing that really impresses me is your profound faith.”[10]

Lech Walesa’s name is synonymous with Solidarity; “He became more than just a symbol of what had been accomplished, he became the very embodiment of Solidarity.”[9] Walesa’s ability to earn the trust of the people ensured that they never lost faith, regardless of how severe the backlash from the regime was. In a letter to Walesa, one Solidarity member highlights the reason for his admiration of the movement’s leader: “You have shown us that we mustn’t be frightened off by police truncheons, nor by ridicule, nor lack of faith. The other thing that really impresses me is your profound faith.”[10]

While Walesa was the face of the movement, he benefited from a great deal of support from other leaders, including women whose leadership has gone largely unnoticed. Though some, like Anna Walentynowicz, were among the top leaders of Solidarity, others played a vital role as community leaders. Some women took on dangerous missions because of their ability to evade internal security forces, who always suspected men of carrying out dissident activities. It is no coincidence that many of these female leaders eventually earned powerful positions in free Poland for which they fought so courageously.[11]

Though not on the front lines, Pope John Paul II’s role in the liberation of Poland cannot be understated. His visits to Poland and speeches around the country attracted and motivated millions of Poles. In fact, British scholar Timothy Garton Ash and others have argued that movements like Solidarity could not have come to fruition without the inspiration and support provided by the Polish pontiff.[12] Ash writes, “Without the Pope, no Solidarity. Without Solidarity, no Gorbachev. Without Gorbachev, no fall of Communism.”[13] Even Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, acknowledged the pivotal role the Pope played: “It would have been impossible without the Pope,” he said.[14]

The Orange Alternative’s founder Waldemar Fydrych, the Major, was known for his eccentric personality, which was reflected in his artistic works as both a writer and painter. His aesthetic vision shaped the approach the Orange Alternative adopted in its opposition to the pro-Soviet regime. The Major offered a wide array of citizens an alternative, low-risk way to oppose the Communist regime, through the use of absurd and nonsensical symbols. Above all else, the group’s paintings of dwarves became a symbol of democratic subversion in Poland during the period of martial law that began in December 1981.[15]

Civic Environment

The efforts of Pope John Paul II, the Solidarity Movement and the Orange Alternative occurred in an environment of severe repression. Under Soviet influence, the Communist government arrested, imprisoned, and occasionally executed opposition leaders without due process. Following the initial success of Solidarity, General Wojciech Jaruzelski of Poland declared a “state of war” and suspended the Constitution in a bid to crush the movement, arresting tens of thousands of Solidarity activists in coordinated police raids between 1982 and 1983.[16]

The efforts of Pope John Paul II, the Solidarity Movement and the Orange Alternative occurred in an environment of severe repression. Under Soviet influence, the Communist government arrested, imprisoned, and occasionally executed opposition leaders without due process. Following the initial success of Solidarity, General Wojciech Jaruzelski of Poland declared a “state of war” and suspended the Constitution in a bid to crush the movement, arresting tens of thousands of Solidarity activists in coordinated police raids between 1982 and 1983.[16]

Lech Walesa faced great adversity as the leader of Solidarity; he was jailed for a year and remained under constant surveillance by the secret police until 1988. In 1983, he did not travel to receive his Nobel Peace Prize, partly out of fear he might not be allowed to return, and partly in solidarity with those who remained in prison: “Could my friends who are imprisoned or paid for the defense of Solidarity with the loss of their jobs accompany me on this day? If not, then it means that the day has not come for me yet to celebrate the awards, even such splendid ones.”[17]

The lack of an independent press and the government’s lack of tolerance for dissent posed obvious challenges for the Polish opposition. Solidarity, however, found a way around these restrictions. Through negotiations with the Communist regime, Solidarity was able to gain an exemption from government censorship for its internal union publications. In essence, a publication could be widely distributed under law if it was stamped “For intra-trade-union use only.” This exemption allowed Solidarity to operate as “an island of freedom” that allowed for “various forms of self-expression by citizens and in effect produced a civil society within its bounds.” In April 1981, Solidarity launched the newspaper Tygodnik Solidarnosc, Solidarity Weekly.[18]

Message and Audience

Human dignity was a central value for all parts of Poland’s anti-Communist struggle. The daily suffering of Poles, particularly the lack of affordable food, was effectively linked to the absence of freedom by Solidarity, the Pope, and the Orange Alternative. Solidarity’s messaging in 1981 reflected this basic value: “History has taught us that there is no bread without freedom.”[19]

Human dignity was a central value for all parts of Poland’s anti-Communist struggle. The daily suffering of Poles, particularly the lack of affordable food, was effectively linked to the absence of freedom by Solidarity, the Pope, and the Orange Alternative. Solidarity’s messaging in 1981 reflected this basic value: “History has taught us that there is no bread without freedom.”[19]

At the core of their message, Solidarity called for mass mobilization efforts on behalf of the Polish people. The movement was able to expand beyond its original base of workers to build a movement reflective of its name – one that united many segments of society. It spread from industrial to agricultural workers with the formation of Rural Solidarity, and it was even able to build bridges with the Polish intelligentsia, despite its labor roots. As the BBC noted, Solidarity “brought books and libraries to the Polish shipyards.” When the Gdansk Accord was reached, achieving Solidarity’s initial goals, one Pole says there was “tremendous hope and a kind of electricity between people…that was one of those moments when, suddenly, millions of people felt that they wanted the same thing, which was free trade unions to represent them against the [Communist] Party.”[20]

The Pope supported the opposition movement in Poland via his position as the head of the Catholic Church, encouraging Polish loyalty to the Catholic Church rather than to the Communist state. Whether his audience was the Polish people or the international political community, the Pope’s message emphasized the values of freedom and liberty, providing moral support to the opposition movement in Poland. A landmark moment was the Pope’s 1979 visit; John Paul II had hoped that by visiting Poland, he could rouse the spirits of his Polish compatriots in opposition to the Communist regime. Despite a prediction by the regime that only dozens of Poles would show up for the Pope’s visit, millions came to greet him, embarrassing the Communist regime. Pope John Paul II mobilized Polish citizens who were eager to embrace their country’s faith, tradition, and historical origins, rather than rejecting them as Communism dictated.

The Orange Alternative amassed popular support through humor and by embarrassing the ruling authorities with slogans like “Citizen, help the militia, beat yourself up.” The Orange Alternative was “a mirror, held up to illuminate the foibles, blemishes and absurdities of the system, by reducing to absurdity the actions of the authorities.” The Orange Alternative sought to engage as universal an audience as possible. Some claim that its choice of the color orange represented a middle ground between the Communist left, represented by the color red, and the Church on the ideological right, represented by the color yellow.[21] The color orange later provided inspiration for the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine; it was adopted by Viktor Yushchenko and his opposition coalition as their official party color.[22]

Outreach Activities

Regardless of the different approaches used, bringing down the Communist regime in Poland required mass public participation. Pope John Paul II was able to galvanize millions of Poles by promoting and projecting an image of a strong, free Poland. As the leader of a global religious movement, the Pope was able to utilize his political power by reaching out to governments who supported an independent Poland, such as the United Kingdom. Lech Walesa’s 1983 meeting with the Pope and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s meeting with 5,000 Solidarity leaders in Gdansk, during which she proclaimed, “Nothing can stop you!” stand out as two important moments that enhanced the mass support for the movement.[23]

Regardless of the different approaches used, bringing down the Communist regime in Poland required mass public participation. Pope John Paul II was able to galvanize millions of Poles by promoting and projecting an image of a strong, free Poland. As the leader of a global religious movement, the Pope was able to utilize his political power by reaching out to governments who supported an independent Poland, such as the United Kingdom. Lech Walesa’s 1983 meeting with the Pope and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s meeting with 5,000 Solidarity leaders in Gdansk, during which she proclaimed, “Nothing can stop you!” stand out as two important moments that enhanced the mass support for the movement.[23]

Solidarity adopted a doctrine of non-violence, which enhanced its populist image and allowed for mass participation. Thus, it organized a wave of strikes throughout the country that would paralyze the government and pressure them to make concessions. On March 27, 1981, for instance, a nation-wide strike protesting the beatings of 27 Solidarity members mobilized over half a million people, bringing the entire country to a standstill. It was the largest strike in Poland’s history under the Soviet Union, forcing the government to promise an investigation into the beatings.[24]

The Orange Alternative generated excitement within the opposition through its unusual outreach methods. In addition to the peaceful but subversive tactics of graffiti art, the Orange Alternative organized public gatherings that were referred to benignly as “happenings.” In 1988, at the peak of discontent, the Orange Alternative organized a 10,000-person march through the city of Wroclaw wearing orange dwarf hats in what became known as the Revolution of the Dwarves. In this way, the movement’s leaders sought to add a degree of levity to the opposition movement, breaking from the monotony of protests and creating more lighthearted and humorous events for participants.[25] The Orange Alternative’s unique and unexpected modus operandi left the government uncertain of how to respond, one of the many reasons for their success as an activist movement.

The combined efforts of Solidarity, Pope John Paul II, and the Orange Alternative led to significant changes in Poland’s political climate. The first major success came in August 1988, when Poland’s Interior Minister Gen. Czeslaw Kiszczak met privately with Lech Walesa, pleading with him to put an end to the general strikes occurring throughout the country. After completing his side of the bargain, Walesa began a long series of negotiations with Poland’s head of state, Gen. Jaruzelski, over the political status of Solidarity. After four months of grueling debate, Walesa won Gen. Jaruzelski’s support in accepting the return of Solidarity, which was officially announced after a Communist Central Committee meeting on January 1989.[26]

Soon after the ban on Solidarity was lifted, Walesa again sat down with Communist Party leaders to start the Round Table Negotiations, a series of talks between the opposition movement and the government in February 1989. The Round Table negotiations, a government effort to defuse the social unrest, led to a major success for the opposition in the form of the Round Table Agreement of 1989. As the leader of the delegation of opposition leaders, Walesa helped pass the agreement, which legalized independent trade unions, introduced the position of the presidency as a Polish political institution, and created a bicameral legislature.[27]

In addition to the restructuring of Poland’s government branches, the agreement called for parliamentary elections, which brought a landslide victory for Walesa and his Solidarity Party. Solidarity established itself as a legitimate political party, winning 99% of Senate seats and 35% of Sejm (the lower house of parliament) seats. Walesa became the first democratically elected president of Poland in 1990, ending more than four decades of Communism.[28]

Learn More

News & Analysis

Ash, Timothy Garton. “Lech Walesa.” Time. 13 April 1998.

Birnbaum, Norman. “Remember Solidarity! Poland’s Journey to Democracy.” Open Democracy. 25 Aug. 2005.

“Country Report: Poland.” Freedom House. 2009.

Donavan, Jeffery. “Poland: Solidarity — The Trade Union That Changed The World.” Radio Free Europe. 24 Aug. 2005.

“Home page.” Lech Walesa Institute Foundation. 2008.

“Home page.” The Orange Alternative. 1 Dec. 2004.

“John Paul II: A Strong Moral Vision.” CNN. 2005.

“Lech Walesa.” Wikipedia. 8 Feb. 2010.

Misztal, Bronislaw. “Between the State and Solidarity: One Movement, Two Interpretations — The Orange Alternative Movement in Poland.” The British Journal of Sociology 43:1 (March, 1992), pp. 55-78.

“Orange Alternative.” Wikipedia. 19 Jan. 2010.

O’Toole, Fintan. “The Great Contradictions.” The Irish Times. 4 Feb. 2010.

“Pope John Paul’s Crusade against Communism.” CNN. 21 Jan. 1998.

Puddington, Arch. “How Solidarity Spoke to a Nation: A Lesson for Today’s Democratic Insurgents.” Freedom House. 17 July 2012.

“Pope Stared Down Communism in Homeland – and Won.” CBC News Online. April 2005.

Repa, Jan. “Solidarity’s Legacy.” BBC News. 12 Aug. 2005.

Books

Ascherson, Neal. The Polish August: The Self-Limiting Revolution. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981.

Ash, Timothy Garton. The Magic Lantern: The Revolution of ’89 Witnessed in Warsaw, Budapest, Berlin, and Prague. New York: Vintage, 1999. Print.

Ash, Timothy Garton. The Polish Revolution: Solidarity 1980-82. London: Jonathan Cape, 1983.

Cirtautas, Arista Maria. The Polish Solidarity Movement: Revolution, Democracy and Natural Rights. London: Routledge, 1997.

Kemp-Welch, A. The Birth of Solidarity: The Gdansk Negotiations, 1980. London: Macmillan, 1983.

MacShane, Denis. Solidarity: Poland’s Independent Trade Union. Nottingham: Spokesman Books, 1981.

Penn, Shana. Solidarity’s Secret: The Women Who Defeated Communism in Poland. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Potel, Jean-Yves. The Summer Before the Frost: Solidarity in Poland. London: Pluto Press, 1982.

The Orange Alternative – Revolution of Dwarves. Warsaw. 2008. ISBN 978-83-926511-4-7.

Walesa, Lech. A Way of Hope. New York: Henry Holt, 1987.

Walesa, Lech. The Struggle and the Triumph: An Autobiography. Arcade Publishing, 1994.

Zielonka, Jan. “Strengths and Weaknesses of Nonviolent Action: The Polish Case,” Orbis 30 (Spring 1986).

Footnotes

[1] Jerzy W. Borejsza, Klaus Ziemer, Magdalena Hułas. Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes in Europe: Short and Longterm Perspectives. Berghahn Books, 2006. Print: 277.

[2] “A Brief History of Poland: Chapter 13: The Post-War Years, 1945–1990.” Polonia Today Online. 1994.

[3] Zagacki, Kenneth S. “Pope John Paul II and the Crusade Against Communism: A Case Study in Secular and Sacred Time,” Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 4:4 (2001), pp. 689-710.

[4] “Pope John Paul’s Crusade against Communism.” CNN. 21 Jan. 1998.

[5] Ash, Timothy Garton. “Lech Walesa.” Time. 13 April 1998.

[6] Donavan, Jeffery. “Poland: Solidarity — The Trade Union That Changed The World.” Radio Free Europe. 24 Aug. 2005.

[7] Walesa, Lech. “Nobel Lecture.” Nobel Prize. 1997.

[8] Misztal, Bronislaw. “Between the State and Solidarity: One Movement, Two Interpretations — The Orange Alternative Movement in Poland.” The British Journal of Sociology 43:1 (March, 1992), pp. 55-78.

[9] Cirtautas, Arista Maria. The Polish Solidarity Movement: Revolution, Democracy and Natural Rights. London: Routledge, 1997. p. 200.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Penn, Shana. Solidarity’s Secret: The Women Who Defeated Communism in Poland. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2005.

[12] “John Paul II: A Strong Moral Vision.” CNN. 2005.

[13] O’Toole, Fintan. “The Great Contradictions.” The Irish Times. 4 Feb. 2010.

[14] “Pope Stared Down Communism in Homeland – and Won.” CBC News Online. April 2005.

[15] The Orange Alternative – Revolution of Dwarves. Warsaw. 2008. ISBN 978-83-926511-4-7.

[16] Darnton, John. “Poland Restricts Civil and Union Rights; Solidarity Activists Urge General Strike.” New York Times, 14 Dec. 2001. A1.

[17] “Nobel for Lech Walesa.” Solidarnosc. 2006.

[18] Kurczewski, Jacek and Kurczewska, Joanna. “A Self-Governing Society Twenty Years After Democracy and the Third Sector in Poland.” Social Research (2001).

[19] Walesa.

[20] Repa, Jan. “Solidarity’s Legacy.” BBC News. 12 Aug. 2005.

[21] Tagliabue, John. “Wroclaw Journal; Police Draw the Curtain, but the Farce Still Plays.” The New York Times, 14 July 1988.

[22] Redel, Konrad. “Ceremony of Handing in an Orange Dwarf Hat to President Yushchenko.” The Orange Alternative. 12 April 2005.

[23] Dhiel, Jackson. “Poles Cheer Thatcher During Visit to Gdansk; ‘Nothing Can Stop You,’ British Leader Tells Walesa.” Washington Post, 5 Nov. 1988.

[24] MacEachin, Douglas J. U.S. Intelligence and the Confrontation in Poland 1980-1981. University Park: Penn State Press, 1998. p. 120.

[25] Misztal p. 62.

[26] Ash, Timothy Garton. The Magic Lantern: The Revolution of ’89 Witnessed in Warsaw, Budapest, Berlin, and Prague. New York: Vintage, 1999.

[27] Ash, Timothy Garton. “Lech Walesa.” Time. 13 April 1998.

[28] Ibid.