Vision and Motivation

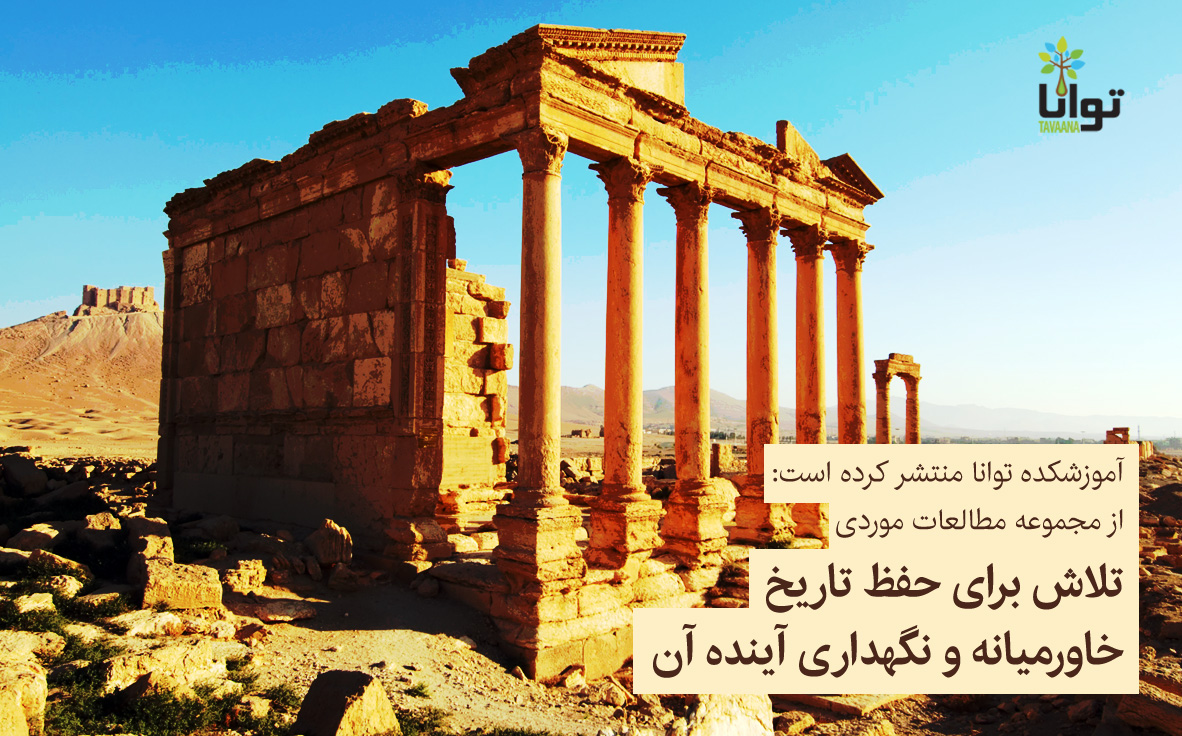

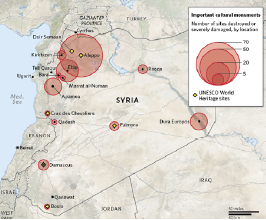

It was May 2015, and ISIStroops were advancing on Palmyra. Located in central Syria, this ancient city had stood at the crossroads of multiple civilizations for thousands of years and boasted priceless art and architecture with a rare blend of classical Roman, Greek and Persian influences.1 “If ISIS enters Palmyra, it will spell its destruction,” warned Syrian antiquities director Mamoun Abdulkarim. “If the ancient city falls, it will be an international catastrophe.”2 Just two months earlier, ISIS had bulldozed the 3,000-year-old city of Nimrud in northern Iraq, following a pattern of destruction the extremists inflicted on each city they took over, from smashing relics at a museum in Mosul to using assault rifles to open fire on irreplaceable statues in Hatra.3

As the jihadists overran the town of Al-Suknah on their way to the “Venice of the Sands,” another group was amassing its own forces to stand against them – not soldiers, but archaeologists, students, and concerned citizens. Palmyra museum staff began packing antiquities into crates to move them outside the region, while a network of volunteers swung into action to enter historic sites, catalogue artifacts, and hide what they could from the oncoming troops.4 When ISIS took Palmyra, bullets flew and mortars exploded around the museum staff as they moved their crates of treasures into a truck. But they were not afraid because, as one says, “We believed that what we were doing was important.” Ten minutes after their escape, ISIS crashed into the museum only to find empty display cases and statues that were too heavy to move without a crane.5

Two of the volunteer groups who are working to save the country’s heritage are led by Syrian archaeologists living outside the country: Heritage for Peace, founded by Isber Sabrine in Spain, and the “Monuments Men” led by US-based scholar Amr Al-Azm, named after the soldiers and scholars who saved European art from the Nazis during World War II. Meanwhile, other groups are using digital modeling to preserve historic sites. Project Mosul uses interactive three-dimensional scans to capture artifacts from the Mosul Museum, while the New Palmyra Project focuses on creating a digital reconstruction of the ancient city. CyArk (short for Cyber Archive), founded by Mosul native Ben Kacyra, uses high-tech laser scanning to document sites down to the millimeter level.6 Perhaps the most prominent of these initiatives is the Institute for Digital Archaeology, a joint project of Harvard and Oxford Universities that works with UNESCO to distribute cheap 3-D digital cameras to local citizens in Syria, Iraq, and other Middle Eastern countries.7

These disparate groups are united by their drive to save the Middle East’s unique cultural heritage. Kacyra, for example, was inspired to work in the digital preservation field when the Taliban destroyed Afghanistan’s ancient Buddhas of Bamiyan in 2001. “It’s senseless destruction, tearing down the fabric of our knowledge, tearing the fabric of our history,” says Kacyra.8 Al-Azm was similarly moved to take action when he witnessed the damage wrought by looting in Syria: “When I saw the destruction, I thought I couldn’t face my children if I just sat by.”9

Goals and Objectives

Syria’s “Monuments Men” banded together in 2012 to informally catalogue damage to historic sites in the Idlib and Aleppo provinces.10 Al-Azm says, “We started to try to see if there was anything we could do to reduce the damage where possible, and more importantly, document what damage was already done.”11 Friends and colleagues from Syrian universities, museums, and government ministries joined to form a nationwide network that now numbers 200 members. “Many of us knew each other before the war because we worked in the same field,” one says. “We started this because we believe so strongly it’s the right thing to do.”12

A large part of these volunteers’ work is documentation of heritage loss, as they visit sites to assess damage and record images with mobile phones or cameras. In some cases, they bury artifacts at risk of being looted and record the GPS location so they can be found later. They even disguise themselves as antiques dealers in order to meet smugglers and photograph the antiquities for sale, then send the photos on to academics in Europe and the United States, who can in turn pass the information on to law enforcement.13 The International Council of Museums has created an Emergency Red List of Syrian cultural artifacts that are in danger of illicit trafficking, intended to help police in Syria’s neighboring countries identify looted art.14

When possible, these networks also attempt to protect precious objects. In March 2015, for example, they worked to defend the Ma’arra museum and its ancient mosaics from bombardment. They smuggled in rolls of protective sheeting, claiming they were burial shrouds in order to maintain secrecy and to ensure the museum wouldn’t be targeted. They were able to wrap up 1,600 square feet of mosaics. The next step was to protect the museum itself by stacking sandbags along its inner walls to shield the mosaics from attack.15 As they have in other cases, they also communicated with the Syrian government to request that the Ma’arra Museum not be targeted – but just three months later, Syrian army helicopters barrel-bombed the site, badly damaging several mosaics and the historic museum building complex.16

The network of volunteers also moves artifacts away from sites at risk of attack. In early 2015, archaeologists in Aleppo transferred 600 medieval manuscripts and astrological devices from the Aleppo Mosque’s library to keep them safe from regime airstrikes.17 However, it is impossible to keep pace with the destruction being wrought by ISIS, proregime forces, opposition troops, and opportunistic looters. Al-Azm says, “With the scale of the damage that’s being done, we’re not winning.”18

However, their efforts go on. Heritage for Peace focuses on holding workshops in Turkey while keeping in touch with those inside Syria via Skype; Sabrine says, “We are really training trainers, then send them inside Syria to train others. It’s a chain.”19 The trainings cover how to catalogue damage in a standardized way and how to best protect sites at risk, while also providing participants with equipment to use in their work.20

Meanwhile, others strive to digitally capture historic sites in order to facilitate future reconstruction in case they are destroyed. CyArk’s advanced laser scanners bounce millions of points off a monument’s surface to capture every crevice, then are combined with high quality photographs to create digital models. The process takes up to a week and costs about $50,000. The final “reality captures” can be used as engineering-grade blueprints for reconstruction, as occurred when the Royal Tombs at Kasubi in Uganda were burned down in 2010 – a year after CyArk had mapped them and made the data publicly accessible. By the end of 2012, the Ugandan government had launched a project to restore the tombs by using CyArk’s digital maps.21

Those behind these digital preservation efforts also hope to provide a massive database of looted art that can be used to make such items impossible to sell. As Roger Michel of the Institute for Digital Archaeology says, “Anything [ISIS] can carry away, they sell…to middlemen in Turkey and other places who are then planning down the road to pretend that some 19th century tweed-wearing gentleman archaeologist pulled these things out of Syria when he was there in 1870. If we have photographs of these objects in Nimrud in 2015 with GPS and time and date data stamped on them, then those objects are going to be forever unsaleable.”22 While Syrians and Iraqis continue the fight to prevent looting and record losses, these digital efforts offer another possibility; as Matthew Vincent of Project Mosul says, “new technology makes it possible to preserve these objects despite having lost their physical reality.”23

Leadership

Those who are struggling to preserve the Middle East’s cultural heritage are dispersed across the region, working in small, loose groups rather than under one umbrella. As Al- Azm says,

“This is not a singular network of people who are under one leadership, all working together and organized. Most of [the work] is done on an ad hoc, individual basis.”24 What coordination takes place is typically limited. For example, Sabrine keeps in close contact with his network on the ground, spending up to 12 hours a day Skyping with them and often losing his voice as a result.25

There are dozens of organizations currently involved in cultural preservation activities for Syria, including some with institutional leadership from major universities and organizations.26 For example, in addition to the Institute for Digital Archaeology run by Harvard and Oxford Universities, the Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria and Iraq Project (SHOSI) is a consortium of the University of Pennsylvania, the Smithsonian Institution, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the US Institute of Peace, Shawnee State University, and the Syrian organization The Day After.27 By and large, however, the volunteers taking action on the ground do so without centralized leadership.

Civic Environment

In Syria, opportunistic looting that began after the outbreak of civil war in 2011 – by soldiers from both pro-regime forces and the opposition Free Syrian Army, as well as by ordinary citizens desperate for a way to feed their families – has given way to “an organized transnational business that is helping fund terror.”28 As ISIS has seized territory in Iraq and Syria, it has also seized the opportunity to profit from the thriving black market in antiquities. After initially allowing independent digs by locals to take place in exchange for a “tax,” ISIS gradually began to increase its control of the trade, first issuing “licenses” to semi-professional field crews, then assigning representatives to oversee their work, and finally becoming more directly involved in the looting.29 In the fall of 2014, the group established an official Archaeological Administration in the city of Manbij, near Syria’s Turkish border, as a means of organizing the sale and transfer of artifacts.30 Looting is now second only to oil as ISIS’s largest source of funding.31

At the same time, ISIS destroys priceless artifacts and historic sites, driven by both extremist ideology and more practical motives. The militants view Shi’a Muslims, Christians, Yazidis, Sufis, Alawites, and other religious minorities as heretics, and their destruction of their religious sites is inseparable from their brutal assaults on their men, women, and children. As one Assyrian activist says, the group “not only despises our religious beliefs but [also] our literature, arts, and history which is irreplaceable and one of a kind. [If this is not stopped] we as a people will be wiped out completely along with our churches, buildings, and history all together.”32 But ISIS’s destruction is also motivated by a more practical consideration: the value of publicity and propaganda. “These are carefully crafted atrocities,” Al-Azm says, “and they send a very specific message that ISIS is here and it can act with impunity, and…the international community is impotent to stop them.”33 Another Syrian says, “Their systematic campaign seeks to take us back into pre-history. But they will not succeed.”34

In a warzone where hundreds of thousands have been killed, tortured, raped, and kidnapped, those who seek to protect their cultural heritage face enormous obstacles and grave risk.35 One individual describes the conditions under which Syrian volunteers are operating: “We were meeting with people who had been without electricity for extended periods and without running water for longer than a month. We were meeting with people who had come under regular barrel bomb attack, who were working in museums and other cultural institutions that had had collateral damage from these bombs – sometimes direct mortar attacks.”36

These brave volunteers face danger on all sides. One of the “Monuments Men” says that the Syrian regime is aware of their activities and is eager to track them down because of their work to expose looting by regime loyalists.37 Furthermore, he adds, “other groups” – including ISIS and the Syrian branch of Al-Qaeda, Jabhat al-Nusra – “could kill us if they knew what we were doing, so we move in the shadows.”38 Perhaps the most high-profile example of such deadly repercussions was the beheading of Syrian archaeologist Khaled Al-Asaad in August 2015 after he refused to tell ISIS where relics from Palmyra had been hidden.39

Because filming and taking photographs immediately arouses suspicion among both proregime and opposition forces in Syria, local citizens must take care when documenting historic sites. Since “a normal camera would be too risky,” some have been using tiny digital cameras hidden inside pens.40 The Institute for Digital Archaeology has also teamed with UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) to distribute low-cost 3-D cameras to volunteers in the region, while telling them to avoid areas under the control of ISIS or its sympathizers.41 In order to further protect them, they set up a three-month lag between when pictures are taken and when they are posted online, so that it will be harder to tell who photographed a particular site. Finally, to bypass the unreliable and slow Internet connections available in the region, cameras are handed out with prepaid mailers so that volunteers can simply mail in memory cards.42 Throughout, “secrecy is an important weapon;” these projects keep their target lists of key historic sites tightly under wraps so that they do not turn into a “hit list” for ISIS.43

A sense of purpose drives those in the region forward through these dangers. One Syrian says, “Sometimes, when I’m dashing across an open square with a sandbag on my back and snipers everywhere, I wonder if I’m not a complete fool.” But he and his colleagues carry on. “Otherwise,” he says, “there will be nothing left in Syria. And then where will we be?”44

Message and Audience

Those trying to save the Middle East’s cultural heritage emphasize the importance of this history, often focusing on the need to preserve it for future generations. According to Kacyra, “Our heritage is much more than our collective memory – it’s our collective treasure. We owe it to our children, our grandchildren and the generations we will never meet to keep it safe and to pass it along.”45

The Syrians and Iraqis leading these initiatives also have a deep understanding of the importance of heritage as a means of building tolerance for other cultures and uniting diverse ethnic and religious groups around a shared history. “Heritage is a tool that can help to achieve peace,” says Sabrine. “People who have learned about the other side’s heritage are better equipped to respect different ethnicities and religions.”46 Another leader of the struggle to rescue Syria’s heritage agrees: “This isn’t just about history. It’s about our future. Saving our heritage is the only thing that can help us rebuild an inclusive Syria after the war.”47

Particularly when pressing politicians to take action on this issue, activists also focus on how the black market in antiquities is bankrolling ISIS’s terrorism; one says, “It’s not just about protecting world heritage, it’s also about protecting life — we know that the sale of these antiquities is funding weapons that are fueling the violence in Syria.”48 Others stress the economic value of Syria’s heritage, as cultural tourism was key to the Syrian economy prior to 2011, and if heritage sites are preserved, they could be an “economic asset for Syrians in the future.”49

However, it can often be difficult to reach ordinary citizens in the region with these messages, as warfare and instability have driven many to looting in order to earn money. One middleman on the Turkish-Syrian border says, “We have been living in a war for more than four years, and people will do anything to feed their kids. I don’t care if the artifact is coming from [rebels] or from ISIS. I just want to sell it.”50

Activists are working with both the Syrian government’s Ministry of Culture and with the opposition to emphasize that “heritage is for everyone” and to convey the need to protect it; Heritage for Peace strives to “show the parties involved that we are neutral, above all [sides] in civil wars like Syria’s.”51 To further these efforts, one activist says, “We are trying to get a Fatwa [religious ruling] from Shariah judges to stop the looting. We are making progress.” However, he adds, they avoid all contact with ISIS, as such efforts would be not only fruitless, but dangerous.52

Outreach Activities

Activists are looking beyond the Middle East to pressure the world to help save the region’s cultural heritage. One archaeologist says that this issue “is not on the agenda, and it’s not getting the attention it deserves, and we’re pushing ‘til that stops.”53 Among the benefits of creating grassroots records of looted artifacts is their use to “sensitize the international community” to the scale and gravity of this ongoing tragedy.54

In 2014, scholars and activists joined with local and international organizations including the Syria Campaign to lobby the United Nations Security Council to ban the trade of undocumented antiquities from Syria, as it did with Iraqi artifacts in 2003. They saw this as a “first step” to reduce the market value for looted goods and “show international solidarity with the activists and archaeologists who are risking their lives on the ground to protect this history.”55 Their campaign included a public petition supported by celebrities such as actor Ian McKellen and an open letter from hundreds of scholars around the world. Leaders of the campaign provided key information to the Security Council’s sanctions monitoring team on how looted antiquities have been funding ISIS and Jabhat Al-Nusra, and they participated in a UNESCO conference where they brought high-level politicians’ attention to the issue. Their efforts ultimately succeeded in February 2015 when the Security Council banned the trade of Syrian antiquities.56

However, they know that more still remains to be done. In July 2015, a bill giving the US government the authority to impose import restrictions on Syrian antiquities moved from approval in the House of Representatives to the Senate for consideration.57 Such legislation has the potential to help, but as Al-Azm points out, “You need both laws and the resources to enforce them. If only one case in 100 is investigated, it is still worthwhile for smugglers to pursue this.”58

While these efforts continue, some activists also emphasize that the destruction of Syria’s cultural heritage is inseparable from the broader crisis there, and that the ultimate solution to both is “a comprehensive and just political resolution to the war.” As two scholars write, “If we truly care about cultural heritage in Syria and Iraq or about the suffering of the people who live there, then our overall objective must be to advocate for a lasting peace.”59

Saving the region’s past can provide a beacon of hope for the future; indeed, some of the destroyed sites embody the long history of tolerance in the Middle East. Before its destruction in 2015, the Roman walled city of Dura Europos in eastern Syria held a legacy of multicultural, multi-religious coexistence: “Christians, Jews, and what we would call pagans lived side by side. The Roman soldiers looked down from the city’s walls on a synagogue and a Christian house church.”60 By preserving such sites for future generations, Syrians and Iraqis can provide a potent reminder of the region’s rich and diverse past and show the way to a future that respects that legacy.

Learn More

News and Analysis

• Bowen, Jeremy. “The men saving Syria’s treasures from Isis.” New Statesman. Sept. 22, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.newstatesman.com/culture/artdesign/2015/09/men-saving-syria-s-treasures-isis>.

• Cassano, Jay. “In The Wake Of ISIS, 3-D Scans Are Saving Iraq’s Cultural Heritage.” Fast Company. June 10, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <https://www.fastcoexist.com/3047045/in-the-wake-of-isis-3-d-scans-are-saving-iraqs-cultural-heritage>.

• Drennan, Justine. “The Black-Market Battleground.” Foreign Policy. Oct. 17 2014. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/10/17/the-black-marketbattleground/>.

• El Deeb, Sarah. “Racing against militant threat to document Syria’s heritage.” Associated Press. Sept. 23, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://bigstory.ap.org/article/77b33fa8ea0c462686e2e0a04eedd725/experts-and-locals-scrambling-documentsyrias-heritage>.

• Elger, Katrin. “Monuments Men: The Quest to Save Syria’s History.” Spiegel Online International. Aug. 4, 2014. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/how-archaelogists-are-trying-to-save-syrian-artifacts-a-983818.html>.

• Farabaugh, Kane. “Activists race to save Syria’s cultural history.” Voice of America. Nov. 7, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.voanews.com/a/activists-racesave-syria-cultural-historyo/3048635.html>.

• Giglio, Mike and Munzer al-Awad. “Inside the Underground Trade to Sell Off Syria’s History.” BuzzFeed News. July 30, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <https://www.buzzfeed.com/mikegiglio/the-trade-in-stolen-syrian-artifacts?utm_term=.kgDPqMpwe#.xs9vj3z7A>.

• Greenberg, Andy. “A Jailed Activist’s 3-D Models Could Save Syria’s History From ISIS.” Wired. Oct. 21 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <https://www.wired.com/2015/10/jailed-activist-bassel-khartabil-3d-models-could-save-syrian-historyfrom-isis/#slide-6>.

• Guensburg, Carol. “In Iraq, Syria, Battling to Preserve Cultural Heritage Under Siege.” Voice of America. March 1, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.voanews.com/a/in-iraq-syria-battling-to-preserve-cultural-heritage/2663070.html>.

• Karmelek, Mary. “The New Monument Men Outsmart ISIS.” Newsweek. Nov. 11, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.newsweek.com/2015/11/20/institutedigital-archaeology-preserves-cultural-heritage-middle-east-392732.html>.

• Kelly, Heather. “The man trying to save ancient sites from ISIS.” CNN Money. Oct. 24, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://money.cnn.com/2015/10/24/technology/digital-preservation-cyark/index.html?category=home-international>.

• Landi, Martina. “A Culture of Peace to Unify Syria: Interview with Isber Sabrine.” Gariwo. May 26, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://en.gariwo.net/culture/arts/aculture-of-peace-to-unify-syria-12882.html>.

• Lindsey, Ursula. “Academics and Archaeologists Fight to Save Syria’s Artifacts.” The New York Times. Aug. 24, 2014. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/25/world/middleeast/academics-and-archaeologists-fight-to-savesyrias-artifacts.html?_r=1>.

• Lynch, Sarah. “The race to protect antiquities in Iraq, Syria.” USA Today. March 18, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2015/03/18/islamic-state-archaeological-artifacts/24703975/>.

• Mackay, Mairi. “Indiana Jones with a 3-D camera? Hi-tech fight to save antiquities from ISIS.” CNN. Aug. 31, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.cnn.com/2015/08/28/middleeast/3d-mapping-ancient-monuments/index.html>.

• Martinez, Jack. “Culture Under Threat: the Fight to Save the Middle East’s Antiquities from Terrorism.” Newsweek. Sept. 24, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.newsweek.com/syria-antiquities-trafficking-threat-isis-376338>.

• O’Brien, Jane. “The international team trying to save Syrian antiquities.” BBC News. July 21, 2014. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-28380674>.

• Parkinson, Joe, Ayla Albayrak and Duncan Mavin. “Syrian ‘Monuments Men’ Race to Protect Antiquities as Looting Bankrolls Terror.” The Wall Street Journal. Feb. 10, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.wsj.com/articles/syrian-monumentsmen-race-to-protect-antiquities-as-looting-bankrolls-terror-1423615241>.

• Schatz, Bryan. “Meet the ‘Monuments Men’ Risking Everything to Save Syria’s Ancient Treasures From ISIS.” Mother Jones. March 6, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2015/02/how-isis-cashes-illegal-antiquitiestrade>.

Multimedia

• Amos, Deborah and Alison Meuse. “In Syria, Archaeologists Risk Their Lives To Protect Ancient Heritage.” NPR Morning Edition. March 9, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2015/03/09/390691518/in-syriaarchaeologists-risk-their-lives-to-protect-ancient-heritage>.

• Borrud, Gabriel and Samantha Early. “Syria and Iraq’s ‘Monuments Men.’” Deutsche Welle. March 20, 2015. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.dw.com/en/syria-andiraqs-monuments-men/av-18330916>.

• Brown, Jeffrey. “Protecting ancient treasures from becoming casualties in Iraq and Syria.” PBS Newshour. Sept. 24, 2014. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/ancient-treasures-casualties-in-iraq-and-syria/>.

• Kacyra, Ben. “Ancient wonders captured in 3D.” TED.com. July 2011. Accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <https://www.ted.com/talks/ben_kacyra_ancient_wonders_captured_in_3d?language=en>.

Image sources:

• http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/23

• http://www.wsj.com/articles/syrian-monuments-men-race-to-protect-antiquities-aslooting-bankrolls-terror-1423615241

• http://www.newsweek.com/2015/11/20/institute-digital-archaeology-preservescultural-heritage-middle-east-392732.html?rx=us

• http://illicitculturalproperty.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/salama-ap-2015-usairaq-syria-illicit-antiquities-trade-150715.jpg

Endnotes:

1 ISIS stands for the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham (an Arabic term referring to Greater Syria). Since proclaiming itself a worldwide caliphate in June 2014, the group has shifted to call itself the Islamic State. It is also known by its Arabic acronym, Da’esh, particularly by its opponents in the Arab world. The extremist group itself wishes to be referred to only as the Islamic State and views the term “Da’esh” as a challenge to its legitimacy.

2 “Isis reaches gates of ancient Syrian city Palmyra, stoking fears of destruction,” The Guardian, May 14, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/14/isis-syria-palmyra-iraq>.

3 Henry Austin, “Palmyra is captured by ISIS; what now for its ancient relics?” NBC News, May 21, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/isisterror/palmyra-captured-isis-what-now-its-ancient-relics-n361996>.

4 Christina Lamb, “Islamic State crisis: Monuments men of Syria guard Palmyra ruins,” The Australian, May 18, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/world/the-times/islamic-state-crisis-monuments-men-of-syria-guard-palmyra-ruins/news-story/e9c21b98a5f59c54182927d49ed96101>.

5 Jeremy Bowen, “The men saving Syria’s treasures from Isis,” New Statesman, Sept. 22, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.newstatesman.com/culture/art-design/2015/09/men-saving-syria-s-treasures-isis>.

6 Heather Kelly, “The man trying to save ancient sites from ISIS,” CNN Money, Oct. 24, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://money.cnn.com/2015/10/24/technology/digitalpreservation-cyark/index.html>.

7 Mairi Mackay, “Indiana Jones with a 3-D camera? Hi-tech fight to save antiquities from ISIS,” CNN, Aug. 31, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.cnn.com/2015/08/28/middleeast/3d-mapping-ancient-monuments/index.html>.

8 Kelly, “The man trying to save ancient sites from ISIS.”

9 Lamb, “Islamic State crisis: Monuments men of Syria guard Palmyra ruins.”

10 Joe Parkinson, Ayla Albayrak and Duncan Mavin, “Syrian ‘Monuments Men’ Race to Protect Antiquities as Looting Bankrolls Terror,” The Wall Street Journal, Feb. 10, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.wsj.com/articles/syrian-monuments-men-race-toprotect-antiquities-as-looting-bankrolls-terror-1423615241>.

11 Kane Farabaugh, “Activists race to save Syria’s cultural history,” Voice of America, Nov. 7, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.voanews.com/content/activists-racesave-syria-cultural-historyo/3048635.html>.

12 Parkinson, Albayrak and Mavin, “Syrian ‘Monuments Men’ Race to Protect Antiquities as Looting Bankrolls Terror.”

13 Ibid.

14 Katrin Elger, “Monuments Men: The Quest to Save Syria’s History,” Spiegel Online International, Aug. 4, 2014, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/how-archaelogists-are-trying-to-save-syrian-artifacts-a-983818.html>.

15 Deborah Amos and Alison Meuse, “In Syria, Archaeologists Risk Their Lives To Protect Ancient Heritage,” NPR Morning Edition, March 9, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2015/03/09/390691518/in-syria-archaeologistsrisk-their-lives-to-protect-ancient-heritage>.

16 Fiona Keating, “Ma’arra Mosaic Museum suffers massive destruction in barrel bomb attack by ‘Syrian army helicopters,” International Business Times, June 20, 2015, accessed at <http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/maarra-mosaic-museum-suffers-massive-destruction-barrel-bomb-attack-by-syrian-army-1507171>.

17 Parkinson, Albayrak and Mavin. “Syrian ‘Monuments Men’ Race to Protect Antiquities as Looting Bankrolls Terror.”

18 Tim Macfarlan, “Palmyra’s ‘Monuments Men’ stash ancient relics before Daesh can destroy them,” Albawaba, May 18, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.albawaba.com/editorchoice/palmyra%E2%80%99s-%E2%80%98monuments-men%E2%80%99-stash-ancient-relics-daesh-can-destroy-them-695850>.

19 Ibid.

20 Parkinson, Albayrak and Mavin, “Syrian ‘Monuments Men’ Race to Protect Antiquities as Looting Bankrolls Terror.”

21 Kelly, “The man trying to save ancient sites from ISIS.”

22 Mackay, “Indiana Jones with a 3-D camera? Hi-tech fight to save antiquities from ISIS.”

23 Ibid.

24 Carol Guensburg, “In Iraq, Syria, Battling to Preserve Cultural Heritage Under Siege,” Voice of America, March 1, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.voanews.com/content/in-iraq-syria-battling-to-preserve-cultural-heritage/2663070.html>.

25 Lamb, “Islamic State crisis: Monuments men of Syria guard Palmyra ruins.”

26 Silvia Perini and Emma Cunliffe, “Towards a protection of the Syrian cultural heritage: A summary of the international response, Volume II (March 2014 – September 2014),” Heritage for Peace, October 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.heritageforpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Towards-a-protection-of-the-Syriancultural-heritage_Oct-2014.pdf>.

27 “Emergency preservation activities completed at Syria’s Ma’arra Mosaic Museum,” Penn Museum, March 5, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.penn.museum/information/press-room/press-releases-research/670-syria-emergency-preservation>.

28 Parkinson, Albayrak and Mavin, “Syrian ‘Monuments Men’ Race to Protect Antiquities as Looting Bankrolls Terror.”

29 Mike Giglio and Munzer al-Awad, “Inside the Underground Trade to Sell Off Syria’s History,” BuzzFeed News, July 30, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.buzzfeed.com/mikegiglio/the-trade-in-stolen-syrian-artifacts#.vpGGMm6JG>. Amr Al-Azm, Salam Al-Kuntar and Brian I. Daniels, “ISIS’ Antiquities Sideline,” The New York Times, Sept. 2, 2014, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/03/opinion/isis-antiquities-sideline.html>.

30 Amr Al-Azm, “The Pillaging of Syria’s Cultural Heritage,” The Middle East Institute, May 22, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.mei.edu/content/at/pillagingsyrias-cultural-heritage>.

31 Parkinson, Albayrak and Mavin, “Syrian ‘Monuments Men’ Race to Protect Antiquities as Looting Bankrolls Terror.”

32 Kareem Shaheen, “Isis destroys historic Christian and Muslim shrines in northern Iraq,” The Guardian, March 20, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/20/isis-destroys-historic-christian-muslim-shrines-iraq>.

33 Farabaugh, “Activists race to save Syria’s cultural history.”

34 Kareem Shaheen and Ian Black, “Beheaded Syrian scholar refused to lead Isis to hidden Palmyra antiquities,” The Guardian, Aug. 19, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/18/isis-beheads-archaeologist-syria>.

35 As of early December 2015, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights estimated the Syrian civil war’s death toll at 330,000, while tens of thousands more had vanished. In addition, the Institute for Economics and Peace found that ISIS killed at least 6,073 people in 2014.

Bryan Schatz, “Inside the difficult, dangerous work of tallying the ISIS death toll,” Mother Jones, Dec. 9, 2015, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2015/12/isis-syria-death-casualty-count>.

36 Jane O’Brien, “The international team trying to save Syrian antiquities,” BBC News, July 21, 2014, accessed Oct. 11, 2016, at <http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-28380674>.

37 Parkinson, Albayrak and Mavin, “Syrian ‘Monuments Men’ Race to Protect Antiquities as Looting Bankrolls Terror.”

38 Ibid.

39 Shaheen and Black, “Beheaded Syrian scholar refused to lead Isis to hidden Palmyra antiquities.”

40 Ursula Lindsey, “Academics and Archaeologists Fight to Save Syria’s Artifacts,” The New York Times, August 24, 2014, accessed Oct. 12, 2016, at <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/25/world/middleeast/academics-and-archaeologists-fight-to-save-syrias-artifacts.html?_r=0>.

41 Jack Martinez, “Culture Under Threat: the Fight to Save the Middle East’s Antiquities from Terrorism,” Newsweek, Sept. 24, 2015, accessed Oct. 12, 2016, at <http://www.newsweek.com/syria-antiquities-trafficking-threat-isis-376338>.

42 Ibid.

43 Mackay, “Indiana Jones with a 3-D camera? Hi-tech fight to save antiquities from ISIS.”

44 Elger, “Monuments Men: The Quest to Save Syria’s History.”

45 Ben Kacyra, “Ancient wonders captured in 3D,” TED.com, July 2011, accessed Oct. 12, 2016, at <https://www.ted.com/talks/ben_kacyra_ancient_wonders_captured_in_3d/transcript?language=en>.

46 Guida Fullana, “The lack of security in Syria during the war has enabled a tremendous amount of trafficking in antiquities: Interview with Isber Sabrine,” Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, March 2014, accessed Oct. 12, 2016, at <http://www.joy-of-elearning.com/portal/en/campus_pau/entrevistes/entrevistes/Isber_Sabrine.html>.

47 Parkinson, Albayrak and Mavin, “Syrian ‘Monuments Men’ Race to Protect Antiquities as Looting Bankrolls Terror.”

48 Justine Drennan, “The Black-Market Battleground,” Foreign Policy, Oct. 17, 2014, accessed Oct. 12, 2016, at <http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/10/17/the-black-market-battleground/>.

49 Andrew Curry, “Archaeologists train ‘Monuments Men’ to save Syria’s past,” National Geographic, Sept. 3, 2014, accessed Oct. 12, 2016, at <http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/09/140903-syria-antiquities-looting-culture-heritage-archaeology/>.

50 Giglio and al-Awad, “Inside the Underground Trade to Sell Off Syria’s History.”

51 Fullana, “The lack of security in Syria during the war has enabled a tremendous amount of trafficking in antiquities: Interview with Isber Sabrine.”

52 Parkinson, Albayrak and Mavin. “Syrian ‘Monuments Men’ Race to Protect Antiquities as Looting Bankrolls Terror.”

53 Lindsey, “Academics and Archaeologists Fight to Save Syria’s Artifacts.”

54 Ibid.

55 Amr al-Azm, “Open Letter Calling on UN to Ban Trade in Syrian Artifacts,” The Syria Campaign, Sept. 25, 2014, accessed Oct. 12, 2016, at <https://diary.thesyriacampaign.org/un-ban-the-trade-in-syrian-antiquities/>.

56 Amr al-Azm, Facebook post, The Syria Campaign, Feb. 18, 2015, accessed Oct. 12, 2016, at <https://www.facebook.com/TheSyriaCampaign/photos/a.608812989210718.1073741828.607756062649744/798873320204683/>.

57 “Bill to Restrict ISIS’ Ability to Profit from Sales of Antiquities,” Chuck Grassley, United States Senator for Iowa, July 29, 2015, accessed Oct. 12, 2016, at <http://www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/bill-restrict-isis%E2%80%99-ability-profitsales-antiquities>.

58 Kathryn Tully, “How to buy antiquities,” Financial Times, Sept. 4, 2015, accessed Oct. 12, 2016, at <http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/d0784c78-50b0-11e5-b029-b9d50a74fd14.html#axzz3wDq7rNRr>.

59 Abdalrazzaq Moaz and Jesse Casana, “Only an End to the Civil War in Syria Will Solve the Problem,” The New York Times, Oct. 9, 2014, accessed Oct. 12, 2016, at <http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2014/10/08/protecting-syrias-heritage/only-an-end-tothe-civil-war-in-syria-will-solve-the-problem>.

60 Andrew Curry, “Archaeologists train ‘Monuments Men’ to save Syria’s past.”