Vision and Motivation

The Soviet Union and its client states in Eastern Europe, otherwise known as the Eastern Bloc, were authoritarian states which restricted free expression and monopolized control of public discourse, putting all mass media under state control and

censorship. Newspapers such as Pravda acted as mouthpieces of the Soviet Communist Party, while printing presses and radio stations were monopolized by state agencies such as print media’s Goskomizdat and radio and television’s Gosteleradio. Those who distributed material not in political and ideological conformity with the Communist regime faced severe repercussions.

Nevertheless, some countries in the Eastern Bloc enjoyed periods of relative openness and liberalization, even before Mikhail Gorbachev’s reformist policies of glasnost and perestroika ultimately brought about the collapse of the Soviet Union. Such openings, including Nikita Khrushchev’s premiership in the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia’s “Prague Spring” of 1968, inspired some writers, artists, and dissidents to dare producing material outside the purview of the state press. These underground publications, known as samizdat, became famous for skirting strict government censorship and spreading news, literature, and even music across countries and borders. Although reaching a limited readership, samizdat became an essential channel for uncensored communication among Soviet intellectuals and between them and the outside world.

Certain Communist leaders, such as Khrushchev in the Soviet Union and Alexander Dubcek in Czechslovakia, exhibited reformist tendencies and partially liberalized their systems. In doing so, they faced staunch resistance from hardliners in their parties, and opposition to both men’s policies was so great that both were ultimately removed from power. Khrushchev, for example, was forced into retirement by former protégé Leonid Brezhnev, who also ordered Dubcek’s overthrow through the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.[1]

The return to harsher authoritarianism gave impetus to samizdat, as works allowed under Khrushchev were forced back underground. Certain events, such as the show trials of Soviet writers and the Helsinki Accords in 1975, drove a small but determined group of dissidents to highlight their regimes’ failings through samizdat, risking imprisonment and exile to demand respect for human rights. Samizdat continued to act as one of the few outlets for free expression until Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost, or “openness”, allowed dissident or unofficial writings and works to be published openly in the late 1980s.

Goals and Objectives

The term samizdat, originally coined by the poet Nikolai Glazkov, means “I-self-publish”.[2] Samizdat includes the politically-minded essays and newsletters, novels, poetry, and banned foreign works which circulated among dissident and intellectual classes in the Eastern Bloc. The creators of samizdat were motivated by a variety of factors, and the term represents a system of publication rather than a unified ideology. At the outset, most of these writers, poets, and musicians only sought to exercise their creative talents outside the limitations of state media, using samizdat as an outlet for material unacceptable to the official press or recording industry. As political conditions became more restrictive in the 1960s and 1970s, others used the underground press to criticize the human rights and international treaty violations of their regimes.

Although much samizdat was not political, some of the Soviet Union’s most acclaimed literary works were biting critiques of the regime that circulated underground. Varlam Shalamov and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, both former inmates of Stalin’s gulag, authored novels which are credited with exposing and drawing global attention to Joseph Stalin’s forced labor camps, where millions of Soviet citizens were summarily interned and many ultimately died of starvation. Shalamov was most famous for The Kolyma Tales, a series of short stories offering a semifictional account of prisoner life in the Kolyma labor camps.

Solzhenitsyn’s A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich exemplified the unprecedented level of public discourse allowed under Khrushchev, and helped lead to his winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970. Solzhenitsyn’s next work, The Gulag Archipelago, was an expansive and thoroughly detailed indictment of the gulag which drew on the experiences of 227 former prisoners and detailed the hardships they suffered there as well as various aspects of life inside the camp system itself. Solzhenitsyn described the gulag as an archipelago of islands which “crisscrossed and patterned that other country within which it was located, like a gigantic patchwork, cutting into its cities, hovering over its streets. Yet there were many who did not even guess at its presence and many, many others who had heard something vague. And only those who had been there knew the whole truth.”[3]

Solzhenitsyn exposed this parallel world by publishing The Gulag Archipelago as samizdat in 1973. He explained: “I have absorbed into myself my own 11 years there not as something shameful, nor as a nightmare to be cursed: I have come almost to love that monstrous world, and now, by a happy turn of events, I have also been entrusted with many recent reports and letters. So perhaps I shall be able to give some account of the bones and flesh of that salamander [a reference to frozen, prehistoric fish that gulag prisoners found and promptly ate] – which, incidentally, is still alive.”[4] The price Solzhenitsyn paid for this exposure was his arrest, deportation, and loss of citizenship.

While samizdat refers specifically to written works, other forms of underground media actually enjoyed a wider audience in the Soviet Union. This is particularly true of magnitizdat, unauthorized recordings typified by popular “bards” like Bulat Okudzhava, Vladimir Vysotskii, and Aleksandr Galich. These men specialized in avtorskaia pesnia, a style of music which consisted of an individual musician singing poetry and playing an acoustic guitar. While in sharp contrast to the state’s large orchestras and not part of the official music industry, many songs were not overtly political. The artists also could not control or receive payment for distribution of the recordings, making them simply creative expression.[5] While the readership of written samizdat may have numbered only in the thousands, up to a million Soviet citizens listened to magnitizdat recordings and easily copied them on legal reel-to-reel tape recorders instead of typing individual copies of samizdat on the precious few personal typewriters not controlled by the state.[6]

While samizdat refers specifically to written works, other forms of underground media actually enjoyed a wider audience in the Soviet Union. This is particularly true of magnitizdat, unauthorized recordings typified by popular “bards” like Bulat Okudzhava, Vladimir Vysotskii, and Aleksandr Galich. These men specialized in avtorskaia pesnia, a style of music which consisted of an individual musician singing poetry and playing an acoustic guitar. While in sharp contrast to the state’s large orchestras and not part of the official music industry, many songs were not overtly political. The artists also could not control or receive payment for distribution of the recordings, making them simply creative expression.[5] While the readership of written samizdat may have numbered only in the thousands, up to a million Soviet citizens listened to magnitizdat recordings and easily copied them on legal reel-to-reel tape recorders instead of typing individual copies of samizdat on the precious few personal typewriters not controlled by the state.[6]

As a leisure activity, magnitizdat offered a more personal and intimate alternative to official music, as Soviet bards performed songs on their own and for much smaller audiences. Thanks to both a more benign official perception of magnitizdat and its widespread popularity, Soviet officials did not expend considerable effort to suppress it. Nevertheless, Aleksandr Galich lauded underground media in his song “We’re no worse than Horace,” singing “Untruth roams from region to region, sharing her experience with the neighboring Untruth, but that which is softly sung in half-voice resounds, but that which is read in a whisper thunders.”[7]

Leadership

Samizdat was not a movement and did not have a clear leadership or organizational structure. Creating an official opposition was unfeasible in the Eastern Bloc, as its Communist regimes did not tolerate political opposition and security services like the Soviet Committee for State Security (KGB) maintained constant surveillance and pressure on dissidents and suspected opponents. A select group of dissidents, however, were willing to defy the intelligence services and the threat of persecution by criticizing the actions of their respective regimes. That criticism was usually expressed in the form of samizdat, and in the case of Czechslovakia, some of those dissidents would go on to lead the country out of communism and to democracy.

After Soviet forces crushed the Prague Spring in 1968 and occupied Czechoslovakia, the regime embarked on a “normalization” effort, meaning renewed authoritarianism and the persecution of social and cultural undesirables. Such undesirables included the band Plastic People of the Universe, seen as a prominent symbol of dissent against communism and punished accordingly. The band never intended to become a political symbol. Frontman Milan Hlavsa explained that “We just loved rock’n’roll and wanted to be famous… Rock’n’roll wasn’t just music to us but kind of life itself.”[8]

As a rock band that sang Western songs and attracted large numbers of fans, it was nevertheless part of a counterculture that threatened the regime. After having their musicians’ licenses revoked in 1970 and being put on trial in 1976, the band was forced to go underground, with Canadian member Paul Wilson being deported and saxophone player Vratislav Brabenec being forced into exile.[9] The trial took place despite the government’s ascension to the Helsinki Accords the year before, which committed it to the protection of freedom of thought and other civil liberties. The trial of Plastic People of the Universe thus helped a wide range of activists and dissents rally to demand the government follow international human rights norms. According to band member Paul Wilson, “What was significant was that the Plastic People of the Universe were the catalyst that brought these elements together. I’m not saying that there wouldn’t have been a human rights movement in Czechoslovakia without the Plastics, but they became the first sort of ’cause celebre’.”[10]

In January 1977, 240 activists, including writer Vaclav Havel, academic Jan Patocka, diplomat Jiri Hajek, and then 25-year-old activist Anna Sabatova, secretly prepared and signed a petition addressed to the government, called Charter 77, which pointed out the large-scale violations of its treaty obligations and called for greater civic and human rights in Czechoslovakia. Working by consensus and seeking the opinions of all signatories, the leaders of the Charter 77 movement brought together not only prominent intellectuals and artists but also a disparate set of dissident groups, including officially repressed religious organizations, disaffected youth, and Communists expelled from the party after the 1968 invasion.

In January 1977, 240 activists, including writer Vaclav Havel, academic Jan Patocka, diplomat Jiri Hajek, and then 25-year-old activist Anna Sabatova, secretly prepared and signed a petition addressed to the government, called Charter 77, which pointed out the large-scale violations of its treaty obligations and called for greater civic and human rights in Czechoslovakia. Working by consensus and seeking the opinions of all signatories, the leaders of the Charter 77 movement brought together not only prominent intellectuals and artists but also a disparate set of dissident groups, including officially repressed religious organizations, disaffected youth, and Communists expelled from the party after the 1968 invasion.

Anna Sanatova described the unity of the movement in 2008, saying “Charter 77 brought atheists into contact with Christians of all denominations. It united writers and artists with scientists and politicians, as well as laborers and clerks. It also brought together the old and the young. Seventeen-year-old dissidents could rub shoulders with people who had fought against fascist Germany and who served time in Stalinist labor camps.”[11] The movement’s leadership structure was also designed to ensure its perseverance: “The original document also gave three people… the right to serve as spokesmen for the movement and to represent it in its dealings with the state and other organizations… whenever a spokesperson was arrested, someone else was named to replace them.”[12]

Although Charter 77 was suppressed and many of its leaders targeted by the regime, it attracted widespread attention abroad and foreshadowed the fall of the Communist regime a decade later. Sanatova points out that “when the totalitarian regimes of Central and Eastern Europe began unraveling in 1989 — just 12 years later — no one either in the region or abroad could deny that Charter 77 and other similar movements had made a profound contribution to those processes. Such organizations contributed to the collapse of the undemocratic regimes in the former Soviet bloc and in the Soviet Union itself, and they provided the cadres for the first post-totalitarian governments in most of those countries.”[13] Vaclav Havel, one of the leading figures behind Charter 77, later led the Velvet Revolution and become the first President of post-Communist Czechoslovakia.

Civic Environment

After Vladimir Lenin’s death in 1924, Joseph Stalin took control of the Soviet Union and oversaw the most brutally totalitarian era of the Soviet system. For 28 years, Stalin exercised absolute political and social control and sentenced millions to death, imprisonment, exile, and the Gulag, a system of forced labor camps maintained by Stalin’s secret police, the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD). The Great Purge (1937-38) targeted suspected opponents in the Communist Party and suspected subversives in Soviet society, including not only intellectuals and religious figures but also peasants and factory workers.

During the Stalinist era, any piece of writing was potentially dangerous and harshly punished. Osip Mandelstam, a Russian poet who recited a poem criticizing Stalin in a small gathering in 1933, spent the next three years in internal exile before dying on his way to a Siberian prison camp. Other writers, such as Isaak Babel and Boris Pilnyak, were condemned to death and shot by the NKVD.[14]

After Stalin died in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev famously condemned the excesses of the Stalin era in his “secret speech” of 1956. Although his tenure was by no means “free”, Khrushchev’s leadership was accompanied by a limited “thaw” that dismantled the Stalin regime’s most extreme tools of repression. The gulag system was largely closed down, the secret police was weakened, and the Soviet Union embarked on new cultural and athletic exchanges with other countries. It was under Khrushchev’s rule that samizdat and magnitizdat became prominent in the Soviet Union, as the production of material not in accordance with official ideology no longer carried a death sentence. The Khrushchev thaw saw the publication of provocative materials like Solzhenitsyn’s A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and the political rehabilitation of many of Stalin’s former prisoners.

After Khrushchev’s fall from power, his successors sought to roll back the reforms he had instituted and push the Soviet Union back in a more Stalinist direction. Leonid Brezhev’s tenure as Premier, known as the “stagnation period” of the U.S.S.R., took away the limited freedom of expression that Khrushchev had granted to writers and artists in the Soviet republics and, by extension, in Communist Eastern Europe. Though not as brutal as Stalin, authorities in the Eastern Bloc under Brezhnev and successor Yuri Andropov used imprisonment and exile to silence dissidents while rapidly expanding censorship of their work. Up until the time Gorbachev came to power, the Soviet Union developed a massive system of spetskhran, or “restricted access collections,” that included all manner of both Russian-language and foreign works, and denied the Soviet public access to them. The largest such collection, the Lenin State Library, contained more than 1,000,000 items by 1985.[15]

As far as pro-human rights and pro-democracy elements in Soviet society were concerned, then-KGB head Yuri Andropov wrote a memo in 1970 which described them as “opposition movements” supported by “imperialist intelligence services and associated anti-Soviet émigré groups” and assured that they were being dealt with: “The Committee for State Security is taking the requisite measures to terminate the efforts of individuals to use “samizdat” to disseminate slander against the Soviet state and social system. On the basis of existing legislation, they are under criminal prosecution; the people who came under their influence have been subjected to preventive measures.”[16]

As far as pro-human rights and pro-democracy elements in Soviet society were concerned, then-KGB head Yuri Andropov wrote a memo in 1970 which described them as “opposition movements” supported by “imperialist intelligence services and associated anti-Soviet émigré groups” and assured that they were being dealt with: “The Committee for State Security is taking the requisite measures to terminate the efforts of individuals to use “samizdat” to disseminate slander against the Soviet state and social system. On the basis of existing legislation, they are under criminal prosecution; the people who came under their influence have been subjected to preventive measures.”[16]

Such “prosecution” was incredibly harsh. The Gulag Archipelago caused Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1974. Natalya Gorbanevskaya, a human rights activist who covered rights abuses through the samizdat publication A Chronicle of Current Events, was forced to spend two years in a psychiatric facility in 1969 and was only allowed to leave the country in 1975.[17] In Czechoslovakia, the most prominent members of the Charter 77 movement met with harsh repression from the government, with Jan Patocka dying after a series of lengthy interrogations by Czechoslovak security forces and Vaclav Havel spending much of the 12 years between 1977 and 1989 in prison.

Message and Audience

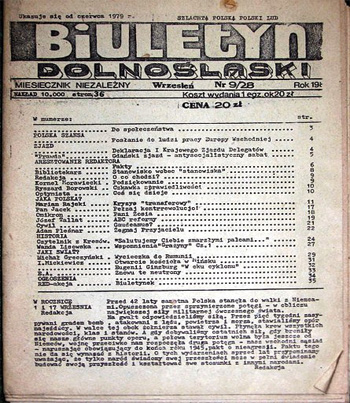

Because of the strict limitations it existed under, samizdat texts circulated in small numbers and were limited to a few elements of Eastern Bloc societies. Without access to printing presses, writers were limited to the copies they could produce themselves or have reproduced by their readers, who would type additional copies and distribute them by hand to trusted circles of friends. Samizdat, due to the process involved in creating it, took on a very particular appearance and form. Due to the risk of reprisals and inability to publish officially, many samizdat writers used pseudonyms and did not take credit for their work. On the other hand, as individuals were responsible for making their own copies of works they received, many took it upon themselves to make edits, alternations, and omissions in the texts, causing them to change as they moved from person to person.

Even within small circles of dissidents, activists, intellectuals, writers, and artists, underground samizdat publications conveyed a variety of messages and targeted disparate audiences. Journals were often produced by members of a certain subset of society, such as a repressed religious organization or a group of rock music enthusiasts, and addressed issues pertaining to that community.[18] Given the outlet that samizdat provided for the well-established Russian literacy scene, for example, some of the Soviet Union’s greatest literary works were produced as samizdat texts, as underground publishing freed books from the requirement to conform to ideologically approved portrayals of socialism and society. Except for those involved in samizdat, residents of the Soviet Union did not gain access to such books until Gorbachev came to power.

One element of the underground which garnered considerable attention from the KGB and Western observers was the human rights community in the Soviet Union, and one of the most prominent publications it produced was the Chronicle of Current Events, a newsletter dedicated to accurate reporting of human rights violations and written by dissident Natalya Gorbanevskaya and a group of collaborators. The Chronicle, which began every issue with Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression…”), published issues regularly from 1968 until 1983.[19] Gorbanevskaya and her collaborators, like the members of Charter 77, did not advocate the overthrow of the regime; such a message would have put them at even greater risk. Despite being labeled as “dissidents,” these activists pushed for the respect of human rights as a moral obligation and the responsibility of the Soviet state, particularly after it ratified the Helsinki accords.[20]

In publicizing trial proceedings and other information kept out of state media, the Chronicle acquired a reputation for strict objectivity and accuracy, despite being continuously retyped by a wide range of people; the central editors of the journal specifically asked their “volunteer publishers” to type additional copies for distribution but to avoid mistakes.[21] Aleksandr Cherkasov, a Russian human rights activist who has compiled all of the Chronicle‘s publications online, explains why its straightforward and objective style put it in sharp contrast with state-run propaganda outlets like Pravda: “There are almost no assessments there, just facts. And this composure, this outwardly serene perception of everything that happens, without hysterics, without emulating those who pressured this independent activity — this was perhaps one of the most important features of the dissident movement in the Soviet Union. Not to emulate the adversary, because otherwise you start resembling him.”[22]

The audience for samizdat included not only those members of their societies that were willing to run the risks of being caught with such material, but also many in the West. Samizdat publications received a great deal of attention from Western activists, human rights and literary organizations, and even intelligence agencies. Samizdat writers took advantage of this attention, sending their work abroad to be published in large quantities and funneled back into the Eastern bloc in a process known as tamizdat, or “published over there”. Gorbanevskaya’s Chronicle of Current Events, for example, was translated into English by Amnesty International and published by that organization until 1984. Works such as The Gulag Archipelago, while unpublished in the Soviet Union, were also translated into English and other languages and found large audiences in the United States and Western Europe.

As a result, when dissidents involved came under harassment from their regimes, those international audiences publicized their plights and pressured Communist authorities on their behalf. While Gorbanevskaya was repeatedly imprisoned in mental institutions, American singer Joan Baez discussed and praised her at her concerts. While Vaclav Havel and his collaborators prepared to submit Charter 77 to the Czechoslovak government, they also arranged for the Charter to appear in major Western newspapers, such as The Times of London, France’s Le Monde, and American newspapers like the New York Times and the Washington Post soon after.[23] The attention that these works drew to their authors and the issues that they discussed became a source of embarrassment for the Communist regimes and limited the reprisals they could subject the most well-known dissidents to.

Outreach Activities

The considerable attention that samizdat received in the West turned into one of many fronts of the Cold War, with both Russian émigrés and Westerners publishing samizdat writings outside of the Eastern Bloc and even attempting to funnel them back in. Western intelligence agencies allegedly took part in tamizdat, whether by publishing texts themselves or encouraging others to do so. In the context of their rivalry with the Soviets, agencies like the Central Intelligence Agency are claimed to have used samizdat in order to bolster dissident movements inside the Soviet Union, as well as to embarrass the Soviet government internationally. One of the most well-known examples of samizdat, Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, illustrates the interplay between such actors and the effect of samizdat on international diplomacy.

The considerable attention that samizdat received in the West turned into one of many fronts of the Cold War, with both Russian émigrés and Westerners publishing samizdat writings outside of the Eastern Bloc and even attempting to funnel them back in. Western intelligence agencies allegedly took part in tamizdat, whether by publishing texts themselves or encouraging others to do so. In the context of their rivalry with the Soviets, agencies like the Central Intelligence Agency are claimed to have used samizdat in order to bolster dissident movements inside the Soviet Union, as well as to embarrass the Soviet government internationally. One of the most well-known examples of samizdat, Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, illustrates the interplay between such actors and the effect of samizdat on international diplomacy.

Doctor Zhivago recounts a love story in the context of the Russian Revolution and the early years of the Soviet Union. Pasternak’s stark and unflattering presentation of the revolution and the actors involved, including the Bolsheviks, led the book to be seen by Soviet authorities as criticism of the regime; Foreign Minister Dmitry Shepilov called it “a malicious libel of the USSR”.[24] Despite Khrushchev’s “thaw”, the book was denied publishing. In order to get around this restriction and get his book published, Pasternak worked with a wealthy Italian Communist and publisher, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli. Feltrinelli arranged for the manuscript of Doctor Zhivago to be smuggled to Italy, translated into Italian, and then put into print by his publishing company. The KGB and the Italian Communist Party, however, attempted to pressure both Pasternak and Feltrinelli into abandoning the book’s publication, forcing Pasternak to write a letter stating “I am now convinced that what I have written can in no way be considered a finished work… Please be so kind as to return, to my Moscow address, the manuscript of my novel Doctor Zhivago, which is indispensable to my work.”[25]

The Soviet government’s efforts failed, and in a later letter to Feltrinelli, Pasternak expressed his delight that publication had gone ahead: “We shall soon have an Italian Zhivago, French, English, and German Zhivagos – and one day perhaps a geographically distant but Russian Zhivago! And this is a great deal, a very great deal, so let’s do our best and what will be will be!”[26]

Their failure to prevent Doctor Zhivago from going into print was an embarrassment for the Soviet authorities. Pasternak was attacked in the state-run press and placed under increasing economic pressure, while Feltrinelli was expelled from the Italian Communist Party. The novel, however, was such a resounding success in the West that it earned Pasternak a nomination for the Nobel Prize in Literature, a prize for which he had been nominated several times before.[27] In addition to the threat of government reprisals against Pasternak, one major obstacle to awarding him the prize was the fact that the book was not available in its original Russian. In order to ensure that Pasternak won the prize and further embarrassed the regime, the CIA is alleged to have intervened, using subsidiaries in Europe to publish a Russian edition of the book and releasing it a month before the Swedish Academy announced the prize winners.[28] While the CIA has refused to comment and Pasternak’s son denies any such involvement, the Academy ultimately granted the Prize in October 1958 and made him an international celebrity. The government refused to allow the author to travel to Stockholm for the ceremony, threatening him with exile if he left the country.[29] The government also banned David Lean’s 1965 film adaptation of Doctor Zhivago, which nonetheless won international acclaim. Ultimately, Pasternak’s novel, the accolades it garnered, and the Soviet Union’s attempts to sabotage the author and his work did considerable damage to the regime’s reputation abroad at the height of the Cold War.

Stories such as those of Pasternak, Solzhenitsyn, and Gorbanevskaya often fueled a perception of underground publishing in the Soviet Union as political defiance of a totalitarian regime, but the works that made up samizdat included a much more diverse range of reporting, writing, music, and art. While samizdat did not directly lead to the collapse of the Soviet Union, it provided a rare outlet for free expression in a closed society and stood in sharp contrast to state propaganda and misinformation. In the case of writers such as Solzhenitsyn, samizdat shed light on the worst crimes of the Soviet regime and brought them to the attention of a global audience. In Czechoslovakia, on the other hand, the effort involved in the creation of the Charter 77 document by the country’s disparate dissident movements and set the stage for the Velvet Revolution led by Havel. In light of the technology available to activists and writers in the present-day, with the internet, blogosphere, and social media making the dissemination of information easy and its censorship far more difficult, the challenges and the dangers faced by Soviet citizens in communicating freely are a testament to their determination and persistence in overcoming them.

Learn More

News & Analysis

Wikipedia article – Eastern Bloc information dissemination.

Wikipedia article – Censorship in the Soviet Union.

Gulag Archipelago online (PDF).

A Chronicle of Current Events – Issues translated and published by Amnesty International.

Full archive of the A Chronicle of Current Events.

RT Russiapedia – Aleksandr Galich biography.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – Commencement address at Harvard University, 1978.

Multimedia

Example of magnitizdat – Aleksandr Galich, pam’ati Bloka.

Footnotes

[1] Medvedev, Roy. “THE WORLD: A Voice from Moscow; Burying the Brezhnev Era’s Cult of Stagnation.” The New York Times. April 17, 1988.

[2] Komaroma, Ann. “The Material Existence of Soviet Samizdat.” Slavic Review, Vol. 63, Autumn 2004.

[3] Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr, translated by Thomas P. Whitney. The Gulag Archipelago, Parts I-II. Harper & Row. Preface, p. X.

[4] Ibid. p.XII.

[5] Daughtry, J. Martin. “Sonic Samizdat: Situating Unofficial Recording in the Post-Stalinist Soviet Union.” Poetics Today, Spring 2009. p.52.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Daughtry p.37.

[8] Stoppard, Tom. “Did Plastic People of the Universe topple communism?” Times Online. December 19, 2009.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Velinger, Jan. “Paul Wilson – the impact of the Plastic People on a communist universe.” Radio Praha. May 31, 2005.

[11] Sabatova, Anna. “From 1968 to Charter 77 to 1989 and Beyond.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. August 19, 2008.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] R. Eden Martin, “Collecting Mandelstam.” The Caxtonian, November 2006.

[15] Stelmakh, Valeria D. “Reading in the Context of Censorship in the Soviet Union.” Libraries & Culture. Winter 2001.

[16] Gribanov, Alexander. “Samizdat according to Andropov.” p.100.

[17] “Russia: Chronicling A Samizdat Legend.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. May 3, 2008.

[18] Komaromi, Ann. “Samizdat and Soviet Dissident Politics.” Slavic Review, Spring 2012.

[19] “Russia,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Komaromi, Ann. “Samizdat and Soviet Dissident Politics.” Slavic Review, Spring 2012.

[22] “Russia.” Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

[23] “Charter 77 After 30 Years.” The National Security Archive. George Washington University.

[24] Finn, Peter. “The Plot Thickens.” The Washington Post. January 27, 2007.

[25] Carlo Feltrinelli, “Comrade millionaire.” The Guardian, November 2, 2001.

[26] Ibid.

[27] “The Plot Thickens.”

[28] Tolstoi, Ivan. “Was Pasternak’s Path to the Nobel Prize Paved By the CIA?” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. February 20, 2009.

[29] “The Plot Thickens.”