Vision and Motivation

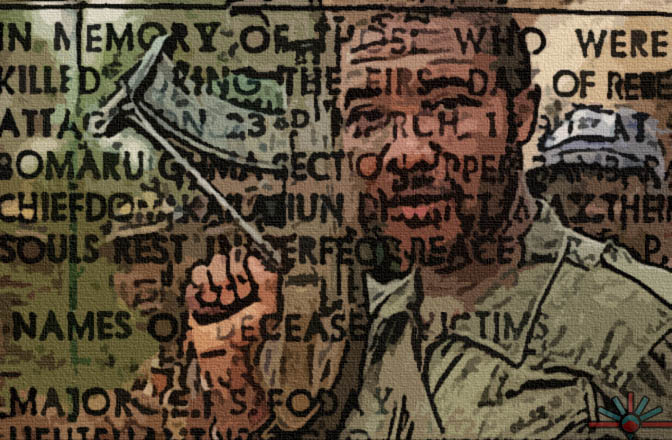

For Liberians, 2003 marked the fourteenth year of a relentless and bloody civil war. After coming to power in a coup in 1989, President Charles Taylor struggled to keep control over a country divided by rebel factions. Both the rebels and Taylor’s dictatorial regime inflicted severe harassment and violence on the people of Liberia in the course of the inter-ethnic struggle; by 2002, over 200,000 people had died, and a third of the country’s population was displaced.[1] Although the consequences of war spared few Liberians, women bore the brunt of the suffering. While the armed combatants were almost entirely male, women and girls regularly faced sexual assault and rape. Others were abducted, abused as forced laborers, or forced to marry the rebels. Those women who escaped such a fate were left with the task of caring for children and the elderly in the face of horrific conditions.[2]

During the years of warfare, Liberian women “had to endure the pain of watching their young sons…be forcibly recruited into the army. A few days later these young men would come back into the same village, drugged up, and were made to execute their own family members. Women had to bear the pain of seeing their young daughters…be used as sex slaves at night and as fighters during the day…[w]omen had to sit by and watch their husbands, their fathers be taken away. In most instances these men were killed, and some of them were hacked to pieces.”[3]

Unable to tolerate yet another year of fighting, in April 2003 a group of Liberian women launched a non-violent campaign for peace, uniting under the words of their leader Leymah Gbowee: “We would take the destiny of this tiny nation into our own hands.”[4] Gbowee declared, “In the past we were silent, but after being killed, raped, dehumanized, and infected with diseases…war has taught us that the future lies in saying NO to violence and YES to peace!”[5] In a society where ethnic and religious tension was rife, women from Muslim and Christian organizations, of both indigenous and elite Americo-Liberian classes, united to form Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace.

Goals and Objectives

After years of economic impoverishment, instability, and violence, there appeared to be no end in sight to the struggle for ethnic-political supremacy. Nor was there willingness on either side to negotiate a solution for peace in Liberia. Taylor proclaimed that he would never negotiate with rebels, and would fight until the last solider died rather than give up sovereignty to international peacekeepers.[6] As the country fell more deeply into a state of chaos and destruction, women grew increasingly and systematically marginalized. Though women felt most acutely the consequences of conflict, they were largely absent from any peacemaking efforts.[7]

The West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP), a regional peacebuilding association based in Ghana, realized the gravity of the situation and voiced growing concern over the status of women in Liberia, as well as the women of other war-torn nations in West Africa. In 2001, WANEP established the Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET).[8] WIPNET was founded on the premise that “systematic violence against women such as rape, forced prostitution, mutilation, etc., was an expression of a deeper systemic disregard for women existing in West African societies….By using women’s numerical strength and their ability to mobilize around key issues, it would be possible to ensure that they could play a central role in formal peace processes and decision-making in the region.” [9] WIPNET operated in several West African countries, holding workshops in conflict resolution and mediation, empowering rural and marginalized women, and opposing community violence.[10] In the Liberian branch, the initial organization meeting was comprised of only four women. However, the WIPNET general network of women increased exponentially, with over five hundred women in regular attendance at its peak in mid-2003.[11]

The West Africa Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP), a regional peacebuilding association based in Ghana, realized the gravity of the situation and voiced growing concern over the status of women in Liberia, as well as the women of other war-torn nations in West Africa. In 2001, WANEP established the Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET).[8] WIPNET was founded on the premise that “systematic violence against women such as rape, forced prostitution, mutilation, etc., was an expression of a deeper systemic disregard for women existing in West African societies….By using women’s numerical strength and their ability to mobilize around key issues, it would be possible to ensure that they could play a central role in formal peace processes and decision-making in the region.” [9] WIPNET operated in several West African countries, holding workshops in conflict resolution and mediation, empowering rural and marginalized women, and opposing community violence.[10] In the Liberian branch, the initial organization meeting was comprised of only four women. However, the WIPNET general network of women increased exponentially, with over five hundred women in regular attendance at its peak in mid-2003.[11]

WIPNET identified several fundamental problems with the peace and conflict resolution process in Liberia. First, there was a gap between the participation of men and women in the peacemaking process. Second, because they had little place in discussions, women’s needs were not being met in the recommendations for conflict resolution and reconstruction. Third, women who did participate in the peacekeeping process were not being taken seriously and thus were being underutilized. Fourth, in order for peace to occur, women needed to be educated on peace-building theories and skills. All of these problems would be addressed, WIPNET leaders asserted, if women created their own space to organize. WIPNET identified several fundamental problems with the peace and conflict resolution process in Liberia. First, there was a gap between the participation of men and women in the peacemaking process. Second, because they had little place in discussions, women’s needs were not being met in the recommendations for conflict resolution and reconstruction. Third, women who did participate in the peacekeeping process were not being taken seriously and thus were being underutilized. Fourth, in order for peace to occur, women needed to be educated on peace-building theories and skills. All of these problems would be addressed, WIPNET leaders asserted, if women created their own space to organize.[12]

WIPNET’s Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace campaign signified an effort to create a women-only movement for peace. The women’s campaign had three fundamental objectives: that the conflict come to an immediate, unconditional ceasefire, that peace talks take place between the government and rebel forces, and that international intervention forces be deployed to Liberia. [13] The movement did not take a political side; its goal was absolute peace. “We’d been pushed to the wall and had only two options: give up or join up to fight back.” Gbowee recalls, “Giving up wasn’t an option. Peace was the only way we could survive. We would fight to bring it.”[14]

Leadership

Although the structure of WIPNET discouraged a formal leader, its core members elected Leymah Gbowee, a social worker active in the Lutheran Church, to be the coordinator and spokesperson for the Mass Action for Peace. [15] The campaign formed as the Christian Women’s Peace Initiative, with Gbowee appealing to the women of church congregations to unite against both Taylor’s tyrannical regime and the violence of the rebels.[16] Soon, Gbowee’s network of women expanded to include Christians and Muslims alike. Despite years of learned prejudice, these women of different faiths and ethnicities were united by their shared experience as mothers, sisters, daughters, and aunts. The Mass Action for Peace was not simply a place for protest, but also a place of support for these women peacekeepers who had become isolated by years of war.

A gifted orator, Gbowee developed a narrative that expressed how the individual, particularly the woman, suffers daily the consequences of conflict and thus wants only to see its end. In a passionate address to Charles Taylor, Gbowee expressed the purposes of the movement: “We are tired of war, we are tired of running, we are tired of begging for bulgar wheat, we are tired of our children being raped. We are now taking this stand…because we believe as custodians of this society, tomorrow our children will ask us ‘Mama, what was your role during the crisis?’”[17] With this speech, Gbowee stood at the forefront of the movement and became the embodiment of Mass Action for Peace.

Civic Environment

The Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace movement formed during a period in Liberia’s history when civil liberties were extremely limited. In 2002, Taylor imposed a state of emergency to counter the rebel group Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) that was quickly approaching the capital, Monrovia. However, most Liberians believed that the declaration of a state of emergency was simply another attempt to suppress opposition to Taylor’s regime.[18] Human rights advocates, journalists, and other civil society members found themselves under arrest and held as political prisoners; many were tortured and eventually killed by Taylor’s special security and “Anti-Terrorism Unit.”[19] While the independent media in Liberia survived among the corruption, war, and political suppression, they remained subject to harassment and often resorted to self-censorship to ensure their security.[20]

The environment in Liberia was not conducive to any form of protest. During the fourteen years of war, its infrastructure had deteriorated rapidly, and most Liberians lived without running water or electricity. An entire generation had grown up without ever seeing a television, let alone using the Internet.[21] This undoubtedly helped to isolate activists and to obstruct the spread of ideas. While the right to strike and organize remained permitted by law, Taylor cracked down on public gatherings and protests in fear that the message of the protestors would embarrass his administration further in the eyes of the international community.

The environment in Liberia was not conducive to any form of protest. During the fourteen years of war, its infrastructure had deteriorated rapidly, and most Liberians lived without running water or electricity. An entire generation had grown up without ever seeing a television, let alone using the Internet.[21] This undoubtedly helped to isolate activists and to obstruct the spread of ideas. While the right to strike and organize remained permitted by law, Taylor cracked down on public gatherings and protests in fear that the message of the protestors would embarrass his administration further in the eyes of the international community.

However, the women of the Mass Action for Peace were not dissuaded by the intimidation, and found ways to continue their peaceful protest. Although the movement formed in response to the marginalization of women, WIPNET members actively embraced and organized around their identity as women. They continually referred to their status as sisters, mothers, and wives – all acceptable and valued female roles in Liberian society – in order to emphasize a peaceful and nonthreatening stereotype of women. “Policymakers are sympathetic to the word ‘woman,’ because they remember how well their mothers took care of them,” Gbowee noted.[22] This sentiment allowed WIPNET a level of access to both combatants and government officials that other groups may have been unable to attain.[23]

Message and Audience

By March 2003, LURD’s anti-Taylor coalition of warlords had gained control of approximately two-thirds of the countryside.[24] Although the dictatorial Taylor began to lose power, the violence persisted. The Mass Action for Peace needed its message to reach the combatants. With the prospect of a rapid ceasefire looking doubtful, they decided to expand their efforts by gaining the support of Liberian religious authorities. They took their message first to bishops and church clergy members with the means to exert significant pressure on Taylor’s government. They then enlisted the support of imams who held influence over the warlords, holding meetings after Friday prayer to engage the imams in dialogue.[25]

Despite the tenuous state of the Liberian media, the Catholic Church-owned radio station Radio Veritas publicized the women’s peaceful forms of protest. Soon WIPNET and its Mass Action for Peace gained the attention of the mainstream news both in and outside of Liberia. [26] This media coverage heightened the frequency and scope of the Mass Action for Peace’s activism. Rallying around a centrally located fish market, the women sang and prayed for hours on end. As a representation of their unity and shared commitment to peace, all in attendance wore only white and removed all jewelry and makeup, thereby concealing indications of class or religious difference.[27] They carried a banner that declared, “the women of Liberia want peace now,” and even held a “sex strike.” This form of protest, documented even in ancient Greece by playwright Aristophanes, was deployed by the women to pressure their husbands to become involved in promoting the peace talks.[28] Membership of the Mass Action for Peace soon increased to the thousands.

The movement refused to take sides in the conflict, and specifically avoided discussion of politics or government actions in order to focus solely on peace. Their activism aimed to persuade both sides to find a peaceful solution to the conflict. They actively sought an audience with President Taylor, even occupying a soccer field on the route that Taylor took to and from his office. When, in April 2003, Taylor granted them a hearing, over 2,000 women congregated outside the executive mansion and pled their case for peace. Both the women’s mass mobilization, and the fear of ostracism from the international community, convinced Taylor to promise to attend peace talks in Ghana.[29] After Taylor agreed to participate in talks, the Mass Action for Peace faced the task of persuading the rebels as well. They sent representatives to confront the rebel leaders in Sierra Leone. Women lined the streets around the rebels’ hotels until the rebels finally agreed to attend. “At first they were bitter, they were resisting us, they thought we were supporting Taylor, and then they said, ‘Why did you come?’” WIPNET member Asatu Kenneth remembers. “I spoke in tears, and all the women were crying, and I think they saw it… and we said, no, we are not representing the government of Liberia, we are representing the women of Liberia, and we had a breakthrough.”[30]

The movement refused to take sides in the conflict, and specifically avoided discussion of politics or government actions in order to focus solely on peace. Their activism aimed to persuade both sides to find a peaceful solution to the conflict. They actively sought an audience with President Taylor, even occupying a soccer field on the route that Taylor took to and from his office. When, in April 2003, Taylor granted them a hearing, over 2,000 women congregated outside the executive mansion and pled their case for peace. Both the women’s mass mobilization, and the fear of ostracism from the international community, convinced Taylor to promise to attend peace talks in Ghana.[29] After Taylor agreed to participate in talks, the Mass Action for Peace faced the task of persuading the rebels as well. They sent representatives to confront the rebel leaders in Sierra Leone. Women lined the streets around the rebels’ hotels until the rebels finally agreed to attend. “At first they were bitter, they were resisting us, they thought we were supporting Taylor, and then they said, ‘Why did you come?’” WIPNET member Asatu Kenneth remembers. “I spoke in tears, and all the women were crying, and I think they saw it… and we said, no, we are not representing the government of Liberia, we are representing the women of Liberia, and we had a breakthrough.”[30]

The campaign’s attempt to appeal universally to women, not simply Christians, Muslims, or a particular ethnic or socioeconomic group, was revolutionary in Liberia. It allowed WIPNET to mobilize large numbers of women, even recruiting enough Liberian refugee women in Ghana to sustain pressure while the peace talks occurred. However, as talks continued, the International Criminal Court indicted Charles Taylor for crimes against humanity for his role in funding former Revolutionary United Front rebels in Sierra Leone. He fled back to Liberia, abandoning his delegation and the peace negotiations. However, the women of the Mass Action for Peace refused to lose hope for a peaceful resolution to Liberia’s conflict; they continued to hold vigils at the fish market, the presidential offices, and the Guinean and American embassies.[31]

By July, violence had worsened in Monrovia. Unwilling to tolerate another month of dead-end negotiations, 200 women held a sit-in at the peace talks in Ghana, demanding that the parties come to a conclusion. Authorities attempted to arrest them, but to no avail. When negotiators tried to exit, Gbowee and the women threatened to strip off their clothes, an act that would shame male delegates.[32] Physically barricading the delegates in the assembly room, the women only agreed to leave when the chief mediator met with them and promised to establish a peace agreement. “They started jumping through the windows,” Cecelia Danuweli recalled, “because they knew we were serious and the chief mediator came out, he pleaded with us and we said no, we were not listening to him until the ceasefire was signed. And he got angry, he went in and blasted them. He told them, “if those women out there continue… because they are angry, they will come in here and they will do just what they please, so please, we have to do something, so that those women can leave the place.”[33]

By July, violence had worsened in Monrovia. Unwilling to tolerate another month of dead-end negotiations, 200 women held a sit-in at the peace talks in Ghana, demanding that the parties come to a conclusion. Authorities attempted to arrest them, but to no avail. When negotiators tried to exit, Gbowee and the women threatened to strip off their clothes, an act that would shame male delegates.[32] Physically barricading the delegates in the assembly room, the women only agreed to leave when the chief mediator met with them and promised to establish a peace agreement. “They started jumping through the windows,” Cecelia Danuweli recalled, “because they knew we were serious and the chief mediator came out, he pleaded with us and we said no, we were not listening to him until the ceasefire was signed. And he got angry, he went in and blasted them. He told them, “if those women out there continue… because they are angry, they will come in here and they will do just what they please, so please, we have to do something, so that those women can leave the place.”[33]

Two weeks later, under the women’s demands and threats from the international community to deny Liberia much-needed funding, peace talks finally culminated in an agreement. Charles Taylor was exiled to Nigeria, UN peacekeeping forces entered Monrovia, and a transitional government with warlords in leadership positions formed that later led to democratic elections.[34] On November 23, 2005, Liberia elected Ellen Johnson Sirleaf to the office of president.[35] After two and a half years, the women’s mass action campaign officially ended with the election of the African continent’s first woman president.

Outreach Activities

The strength of WIPNET lay in its ability to build coalitions between West African Christians and Muslims. Gbowee and core WIPNET members first founded the Christian Women’s Initiative from St. Peter’s Lutheran Church, Monrovia, but the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace was only successful when it included the members of the Liberian Muslim Women’s Organization, founded by Asatu Bah Kenneth.[36] Because of its appeal to a shared belief in the power of nonviolence and prayer, the Mass Action for Peace campaign quickly earned the support of religious organizations in Liberia and around the world, including the Church World Service, a faith-based humanitarian organization, and the Lutheran World Federation.[37] However, this interfaith collaboration did not exist without challenges; some Christian members originally worried that working alongside Muslim women would dilute their faith. However, Gbowee insisted that peacemaking must be without discrimination because the dangers of war were indiscriminate: “Does the bullet know Christian from Muslim?”[38]

In Liberia, WIPNET did not disappear from political life when fighting ended. The women of the Mass Action for Peace were key participants in reconstruction efforts. Their position within Liberian communities often made them more effective than their UN peacekeeper partners. Ex-combatants were more cooperative in disarmament campaigns when urged by WIPNET women, who were often familiar members of their community, to give up their weapons. The women’s work during the UN mission solidified their place in peacekeeping efforts, as well as their leadership within Liberian communities.[39] In addition to disarmament, WIPNET members also played a central role in increasing women’s participation in politics. They registered voters, particularly female voters, with great success; women constituted half of the country’s registered voters in the 2005 election of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.[40]

Outside Liberia, lessons learned from the Mass Action for Peace protest spread throughout Africa. In Sierra Leone, WIPNET members led nonviolence activism training in preparation for the 2007 elections and organized the first ever West African Women’s Elections Observation Mission, inviting women from throughout West Africa to observe Liberia’s 2011 elections.[41] Women in other nations replicated the tactics of the Mass Action for Peace to address their own problems; in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, Muslim and Christian women dressed in white peacefully protested to “end the political stalemate and worsening security situation” of their own country in 2011.[42] The success of the Mass Action for Peace emphasized a renewed awareness of the potential of African women in political life that transgressed boundaries. In 2011, the international impact of this movement was confirmed when the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to three women activists: Tawakkol Karman of Yemen, and President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and Leymah Gbowee of Liberia.

WIPNET continues to peacebuild and to advocate against sexual and gender-based violence. Their goal is based on the concept of “never again”: never again should Liberians allow manipulation, prejudice, or abuse from their government. “We are determined to fashion ourselves and our children into a people capable of distinguishing the vultures and the opportunists,” Gbowee declared, “We are determined to fashion ourselves and our children into a people who demand and support good governance and are challenged to participate in it.”[43]

WIPNET continues to peacebuild and to advocate against sexual and gender-based violence. Their goal is based on the concept of “never again”: never again should Liberians allow manipulation, prejudice, or abuse from their government. “We are determined to fashion ourselves and our children into a people capable of distinguishing the vultures and the opportunists,” Gbowee declared, “We are determined to fashion ourselves and our children into a people who demand and support good governance and are challenged to participate in it.”[43]

In organizing for peace, Gbowee and the women of WIPNET modeled the type of world they wanted to see: a world that heard and valued the voices of both women and men, both Christians and Muslims. In her Nobel lecture, Gbowee stressed that the work of the Mass Action for Peace symbolized only the first steps in creating a better Liberia and a better world: “We succeeded when no one thought we would, we were the conscience of the ones who had lost their consciences in the quest for power and political positions…as we celebrate our achievement, let us remind ourselves that victory is still afar. There is no time to rest until our world achieves wholeness and balance, where all men and women are considered equal and free.”[44]

Learn More

News & Analysis

BBC. “Liberia country profile.” 17 Nov. 2010.

Diaz, John. “Post-Civil War Liberia at a Crossroads.” International Reporting Project, 12 Dec. 2010.

Gbowee, Leymah. “Nobel Lecture.” Nobel Peace Prize. Oslo. 10 Dec. 2011. Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Web.

Herbert, Bob. “A Crazy Dream.” The New York Times, 30 Jan. 2009

“Liberia.” Freedom in the World. Freedom House, 2003.

“Women in Peacebuilding (WIPNET).” West African Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP).

“Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 07 Sept. 2013.

Books

Gbowee, Leymah, and Carol Mithers. Mighty Be Our Powers: How Sisterhood, Prayer, and Sex Changed a Nation at War: a Memoir. New York: Beast, 2011

Lederach, John Paul, and Angela Jill Lederach. When Blood and Bones Cry Out: Journeys Through the Soundscape of Healing and Reconciliation. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 2010.

Videos

Gbowee, Leymah. “Peace Activist Leymah Gbowee.” Interview by Tavis Smiley. Tavis Smiley. PBS. 5 Oct. 2011. Television.

Pray the Devil Back to Hell. Dir. Gini Reticker. Fork Films, 2008.

Liberia: An Uncivil War. Dir. Jonathan Stack and James Brabazon. Docurama, 2004.

“Leymah Gbowee accepts 2009 JFK Profile in Courage Award.” JFK Library. 7 Aug. 2009. YouTube.

Footnotes

[1] Pray the Devil Back to Hell. Dir. Gini Reticker. Fork Films, 2008.

[2] “Ending Liberia’s Second Civil War: Religious Women as Peacemakers.” Georgetown University Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. 11 August 2011.

[3] Gbowee, Leyman. “Women and Peacebuilding in Liberia: Excerpts from a talk by Leymah Gbowee at the ELCA’s Global Mission Event in Milwaukee, WI.” Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. 30 July 2004.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Pray the Devil Back to Hell

[6] Gbowee, “Women and Peacebuilding in Liberia: Excerpts from a talk by Leymah Gbowee at the ELCA’s Global Mission Event in Milwaukee, WI.”

[7] “Ending Liberia’s Second Civil War: Religious Women as Peacemakers.”

[8] “Women in Peacebuilding (WIPNET).” West African Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP).

[9] Pedersen, Jennifer. “In the Rain and in the Sun: Women in Peacebuilding in Liberia.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the ISA’s 49th Annual Convention, “Bridging Multiple Divides,” Hilton San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA, Mar 26, 2008, 3.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Lederach, John Paul, and Angela Jill Lederach. When Blood and Bones Cry Out: Journeys through the Soundscape of Healing and Reconciliation. Oxford, NY: Oxford UP, 2010. Retrieved online at The Scavenger.

[12] “A Conversation with Women Peacebuilders: Leymah Gbowee and Shobha Gautam.” The Boston Consortium on Gender, Security and Human Rights. The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, Medford, MA, 8 March 2006.

[13] Gbowee, “Women and Peacebuilding in Liberia: Excerpts from a talk by Leymah Gbowee at the ELCA’s Global Mission Event in Milwaukee, WI.”

[14] Gbowee, Leymah. “The President Will See You Now.” PBS: Women, War, and Peace. 13 September 2011. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/women-war-and-peace/features/the-president-will-….

[15] Pedersen

[16] Pray the Devil Back to Hell.

[17] Afkhami, Mahnaz, and Haleh Vaziri. “Ensuring Safety for Women and Girls: A Practitioner’s Manual.” Women’s Learning Partnership for Rights, Development, and Peace (WLP). 2012. http://tavaana.org/sites/default/files/Victories%20over%20Violence.pdf.

[18] “Liberia.” Freedom in the World. Freedom House, 2003.

[19] Gbowee, Leymah. “The President Will See You Now.”

[20] “Liberia”

[21] Gbowee, “Women and Peacebuilding in Liberia: Excerpts from a talk by Leymah Gbowee at the ELCA’s Global Mission Event in Milwaukee, WI.”

[22] “A Conversation with Women Peacebuilders: Leymah Gbowee and Shobha Gautam”.

[23] Pedersen.

[24] “A Short History of the Conflict in Liberia and the Involvement of NGOs in the Peace Process.” The World Movement for Democracy. http://www.wmd.org/resources/whats-being-done/ngo-participation-peace-ne….

[25] “Ending Liberia’s Second Civil War: Religious Women as Peacemakers.”

[26] Pray the Devil Back to Hell

[27] Pedersen

[28] Afkhami and Vaziri

[29] Ibid.

[30] Pedersen, 7

[31] Sengupta, Somini. “In the Mud, Liberia’s Gentlest Rebels Pray for Peace.” The New York Times, 1 July 2003.

[32] Afkhami and Vaziri

[33] Pedersen, 8

[34] “Liberian Women Act to End Civil War, 2003.” Global Nonviolent Action Database. Swarthmore College. 22 October 2010. http://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/liberian-women-act-end-civil-wa….

[35] “Biographical Brief of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.” The Executive Mansion. http://www.emansion.gov.lr/2content.php?sub=121&related=19&third=121&pg=sp.

[36] Pray the Devil Back to Hell

[37] “Peace Talks, Ceasefire, Humanitarian Aid Crucial for Liberia, CWS Says.” National Council of Churches. 16 April 2003. http://www.ncccusa.org/news/03news46.html.

[38] Pray the Devil Back to Hell

[39] Pedersen

[40] “A Conversation with Women Peacebuilders: Leymah Gbowee and Shobha Gautam”

[41] Gbowee, Leymah. “Peace Activist Leymah Gbowee.” Interview by Tavis Smiley. Tavis Smiley. PBS. 5 October 2011. Television.

[42] Ekiyor, Thelma, and Leymah Gbowee. “In Solidarity with The Women of Cote d’Ivoire.” The Women’s International Perspective. 22 March 2011. http://thewip.net/contributors/2011/03/in_solidarity_with_the_women_o.html.

[43] Gbowee, “Women and Peacebuilding in Liberia: Excerpts from a talk by Leymah Gbowee at the ELCA’s Global Mission Event in Milwaukee, WI.”

[44] Gbowee, Leymah. “Nobel Lecture.” Nobel Peace Prize. Oslo. 10 December 2011. Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB.