Where Books are Burned

A crisp winter breeze cut through the air as hundreds of Muslim men, women, and children filtered through the streets of Bradford, England on a sunny January day in 1989. Signs reading “Rushdie Eat Your Words,” “Rushdie Stinks,” “Ban Satanic Ve[r]ses”[i] swayed back and forth, floating above waves of people coalesced in front of the city’s main public buildings. Supporters of Salman Rushdie, the novelist to whom these statements were addressed, stared aghast at their T.V. sets, where images of protesters dousing in gasoline his controversial novel, The Satanic Verses, appeared before their eyes. In an instant, the faces on the T.V. gleamed, as a spark met the novel’s gas soaked pages. Seeing the novel ablaze, the crowd erupted into cheers.

Nearly two centuries earlier, the German Jewish poet Heinrich Heine famously wrote, “Where they have burned books, they will end in burning human beings.”[ii] Heine’s words proved almost prophetic in the wake of the Bradford book burning. No, no immolations occurred in the city’s public square. Instead, on Valentine’s Day 1989, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa urging Muslims to kill The Satanic Verses’ allegedly blasphemous author.[iii] However, unable to get to the novel’s author, who went into hiding after Khomeini issued his fatwa,[iv] extremists turned to easier targets. On July 3, 1991, they attacked Ettore Capriolo, the 61-years-old Italian translator of The Satanic Verses, inside his apartment in Milan, Italy.[v] Capriolo survived the wounds from their knives, despite their cruel intentions.[vi] Sadly, just days later, on July 12, his Japanese counterpart, Hitoshi Igarashi, did not fair as well. Extremists stabbed Igarishi to death outside his office in northeast Tokyo, Japan.[vii]

The Roots of Division

In the early part of the 20th century, long before crowds gathered in Bradford to burn Rushdie’s novel, the city burgeoned as a textile manufacturing hub. By the time of the book burning, however, the city appeared as but a decayed shell of its once prosperous past. Following World War I, foreign competitors flooded the world market with cheap products, causing an irreversible industrial slump to hit cities like Bradford that could not compete.[viii] With the exception of the World War II period, Bradford has never recovered from this slump.[ix]

It was under these dismal economic conditions that the first wave of mostly Muslim South Asian immigrants arrived to Bradford in the 1950s and ’60s. Initially, the city welcomed them; they were mostly young men looking for work, and Bradford’s manufacturers needed laborers who were willing to work overnight and weekend shifts.[x] As time passed, however, the initial arrivals’ families made the trip to England to join them, and, by 2001, South Asian Muslim immigrants made up Bradford’s largest minority group, accounting for roughly one-quarter of the city’s population, numbering around 75,000.[xi] Resentment arose as, unlike other waves of new immigrants, the Muslim South Asian community overwhelmingly failed to integrate, and a de facto, voluntary segregation between Muslims and non-Muslims became the status quo in Bradford.[xii]

Caution Amidst Burning Cars and Secret Police

In 2001, little more than a decade after the book burning, the tension between Bradford’s Muslim and non-Muslim communities erupted once again; this time, however, violent riots took the place of protests, and the city was wrought with much greater destruction. When all was said and done, £25 million worth of property was damaged and hundreds of police officers suffered injuries.[xiii]

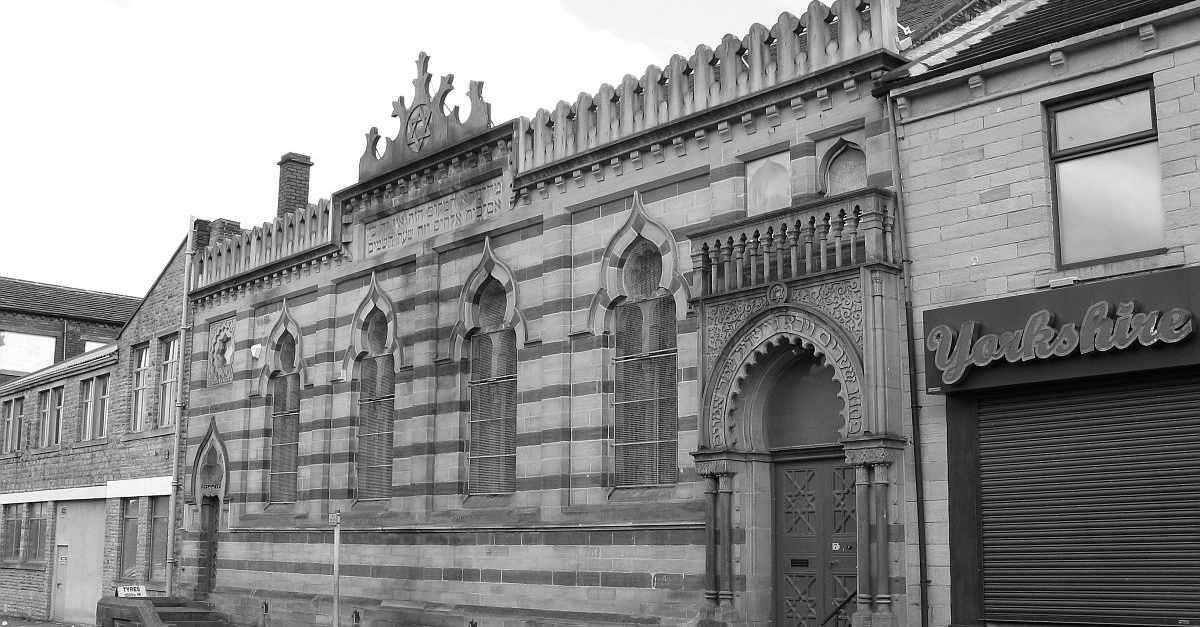

Amidst the chaos of burning cars and smoke-choked streets, Rudi Leavor surreptitiously unscrewed the brass plaque outside of Bradford’s Reform Synagogue. Explaining this action, Leavor, the 89-year-old synagogue chairman, said, “We didn’t want to be the cause of potential trouble.”[xiv] Even though Bradford’s Reform Synagogue stood inconspicuously located, Leavor refused to take any chances; he was no stranger to the hazards of blind hate and prejudice, and his childhood had taught him the value of caution.

Looking back, Leavor recalled the overwhelming fear he felt each time he heard the ferocious sounds of swastika-clad soldiers marching past his family’s home in Germany.[xv] On one cold, frightful morning that is seared into Leavor’s memory, that fear became much starker. That day, as Leavor and his sister were leaving for school, the Gestapo came to their door. The Gestapo, or Nazi secret police, forced their way inside while Leavor’s parents were still in bed, and demanded that Mrs. Leavor, the treasurer of the local ladies Lodge, give them all of the Lodge’s savings.[xvi] Sensing that this was not the end, in November 1937, when Leavor was just 10 years old, the family fled Nazi Germany and sailed to England. Leavor remembers watching transfixed as his father cast their house keys into the rolling waves and said, “That’s the end of Germany for us.”[xvii]

An Unlikely Ally for a Synagogue in Disrepair

In 2013, a different worry-filled Leavor’s mind. The finances of Bradford’s last remaining synagogue were floundering. The city’s century-old Jewish population was fast disappearing; of the many families that once attended the Reform Synagogue, only 45 people remained.[xviii] Making matters worse, the roof leaked, threatening the sacred Torah scrolls. Seeing few available options, the congregation hesitantly contemplated selling the 135-year-old building, as their Orthodox Jewish neighbors had been forced to do with their synagogue two years earlier.[xix] Just then, a seemingly unlikely ally appeared. His name was Zulficar Ali.[xx]

Ali was the manager of one of Bradford’s most popular restaurants, Sweet Centre. Around the same time the Jewish congregation began to seriously consider selling their beloved synagogue, Ali became aware that a rival restaurant intended to open nearby. Ali’s restaurant, it just so happened, was not only a favorite among local lovers of Pakistani food, but, in particular, among many Reform Synagogue attendees.[xxi] Fearing the rival restaurant would damage business, Ali approached Leavor for help. Little did Ali know that Leavor faced his own troubling situation.

After describing his cause for concern to Leavor about the disastrous impact a rival restaurant would have on his business, Leavor agreed to help Ali. The two then, together, successfully rallied enough local support to block the rival restaurant’s planning application. In turn, when Leavor informed Ali of the synagogue’s situation, Ali immediately vowed to return the favor, and promptly secured much needed funds from a local enterprise to pay for emergency roof repairs on the synagogue.[xxii] Aware that those repairs alone were not enough, Ali proceeded to contact the secretary of the local mosque, Zulfikar Karim.[xxiii]

Saving a Synagogue, Bridging a Divide

Even though Karim had grown up only a few blocks away from the synagogue, its existence came as a surprise to him.[xxiv] Learning, for the first time, not only that a synagogue existed in Bradford, but that its existence was in jeopardy, Karim offered his help.[xxv] “I was shocked to hear the news and I immediately reached out to others in the community,” Karim recalled.[xxvi] The gravity of the synagogue’s situation was clear. “There’s been a Jewish community in Bradford for 100 years and now there’s barely a trace,” he lamented.[xxvii]

Quickly, Leavor and Karim set to work to save the synagogue. Together, they obtained considerable support from local community members to begin immediate repairs to the building and applied for a lottery grant that would provide the synagogue with over £100,000. Notably, local businessmen Khalid Pervaiz matched £1,000 that was donated by several individuals, pound for pound.[xxviii] Responding to why he would do so much to help the city’s Jewish community, Karim insisted, “We have so much in common…we both have a tradition of helping each other out in business, and strong entrepreneurial, family and community values.”[xxix]

George Galloway, Member of Parliament from the Respect Party, delighted in the exemplary cooperation between Bradford’s Jewish and Muslim Communities. In early March 2013, he proposed a parliamentary motion to congratulate the city’s Muslim community for its “extraordinary ecumenical gesture.”[xxx] For Leavor and Karim, saving the synagogue was only the beginning of their compassionate inter-community, inter-faith efforts. Well aware that much of Bradford remained troubled by deprivation and extremism and that their limited efforts had not ended the segregation between the Muslim and non-Muslim communities, Leavor and Karim decided that they would try to spread their spirit of cooperation.

Overcoming Radicalism, Intolerance, and Misunderstanding

All four of the bombers who were responsibile for the devastating suicide attacks that occurred on July 7, 2007 in central London lived near Bradford.[xxxi] Due to a soaring youth unemployment rate and bleak educational prospects, the city’s youth remained vulnerable to extremist propoganda. Karim remarked, “You look at those who killed Lee Rigby, supposedly in the name of Islam. The question is: what makes these young men so radicalised, so angry, so intolerant?” Hopeful that there is an answer, Karim declared, “I really, really deeply, strongly feel that the way forward is interfaith dialogue – perhaps through food, perhaps through visiting a synagogue or other places of worship.”[xxxii] Interfaith dialogue is essential for interfaith coexistence. “As a minority you close ranks and don’t move forward so fast for fear of losing or diluting your identity,” explained Ishtiaq Ahmed, spokeperson for the Bradford’s Council for Mosques.[xxxiii] When one community closes ranks and refuses to interact with another community, seeds of mistrust and misunderstanding are sowed.

Attempting to overcome the mistrust and misunderstanding that exists between Bradford’s Muslim and non-Muslim community, the city’s education system is beginning to place greater emphasis on tolerance and intercultural awareneness. Some teachers have started to facilitate exchanges between students from different communities. After one such exchange, involving youngsters from the Shirley Manor primary school and children from Muslim families, Shirley Manor students could be heard saying, “But actually, they like pizza. And they watch television. And one even has an X-box!”[xxxiv] These responses are anything but trivial; they show how ideas about the ‘other’ can become wildly distorted, or even completely false, when there is no interaction between communities, and how dialogue, interaction, and mutual interests can reverse such misunderstandings.

Drawing upon past experience as an organizer of the renowned International Curry Festival, Karim, with Leavor’s help, devised an ingenious plan to unite Bradford’s disparate communities. Under his plan, they would be united around something they all have in common: the love of good food. Following Karim’s plan, Jewish families invited members of the Muslim and Christian communities to share in an Oneg Shabbat dinner, an informal Friday night gathering; the Muslim community then prepared a special Ramadan feast to share with their Jewish and Christian neighbors; and Christians in the community cooked a traditional English meal that included a halal Shepherd’s pie to celebrate the Harvest festival.[xxxv] Food, Karim and Leavor proved, “brings people together.”[xxxvi]

From a City Divided to a City of Sanctuary

The long-held racial tensions in Bradford will not vanish overnight; they are too deeply ingrained. Nevertheless, interfaith dialogue and tireless campaigning against intolerance are gaining ground and have already eroded much of the city’s decades-old barriers to inter-cultural fellowship. On October 1, 2008, the City of Sanctuary movement, which aims to “build a culture of municipal hospitality for people seeking sanctuary” and to “dispel the misconceptions around refugees,” came to Bradford.[xxxvii] Two years later, on November 18, 2010, the City of Sanctuary movement declared Bradford a “city of sanctuary,” making it only the third such city in the United Kingdom.[xxxviii] In explaining the decision, a representative of the movement proclaimed that Bradford has become “a place where a broad range of local organizations, community groups and faith communities, as well as local government, are publicly committed to welcoming and including people seeking sanctuary.”[xxxix]

Bradford’s commitment to tolerance was on full display on August 28, 2010, when an inflammatory rally, begun by the far-right English Defence League (EDL), marched into the city. The EDL believed that the city’s racial and religious divisions could be used to “ignite an inter-communal powder keg.”[xl] While the motley crew of far-right fanatics and football hooligans threw bottles and bricks as they marched through the city’s streets, Bradford residents exercised impeccable restraint and solidarity. Local churches held prayers, Muslims in the community offered police refreshments, women from all backgrounds hung peace ribbons across the streets, and easily excitable youths were kept away from the rally beforehand.[xli] When all was said and done, the hateful rally left the city without succeeding in setting off tensions.

In this new environment, the future of the Reform Synagogue seems bright. Just a year after Leavor and Ali first spoke, the synagogue received the first tranche of a £103,000 lottery grant, and the city council has pledged to give the synagogue an additional £25,000.[xlii] “It was a very pleasant surprise” and a “true mitzvah,” Leavor confided, going on to say, “I was certainly chuffed to have experienced such genorosity, especially at this stage in my life. I’ve been the synagogue secretary since 1953 and this is the biggest thing that’s ever happened to us.”[xliii] Showing a similar sentiment, Karim remarked, “It makes me proud that we can protect our neighbours.”[xliv] Expanding upon this, he earnestly added, “When I met [Leavor], I felt like he was my father, or grandfather. If he were an elder in my community, I would be there for him in his time of need. So I felt – well, it’s my obligation to help him as if he were a member of my own family.”[xlv] The once unlikely allies remain friends. When on holiday, Leavor unflinchingly entrusts Karim with the key to the synagogue.[xlvi] Karim noted soberly, however, “Many people do seem to be massively taken aback that the Jewish and Muslim community are working hand in hand, when all you seem to hear about Bradford are the nasty things.”[xlvii]

Learn More

Articles

Bradford Synagogue Saved by City’s Muslims. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/20/bradford-synagogue-saved-muslims-jews.

In One Hard-knock British City, a Secret Muslim Donor Helps save a Synagogue. http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/jewish-world-features/in-one-hard-knock-british-city-a-secret-muslim-donor-helps-save-a-synagogue.premium-1.525183.

Bradford Muslims Rally to Save Synagogue From Closure. http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2013/03/19/bradford-synagogue-muslims_n_2908254.html.

Rudi Leavor- Berlin-Bradford http://holocaustlearning.org/survivors/Rudi-Leavor.

Footnotes

[i] “UK OBSERVATION : ARCHIVE.” Satanic Verses Bookburning. Bradford, UK. 14 January 1989. Web. 10 Feb. 2015. http://garryclarkson.photoshelter.com/image/I0000EcCGk1pcbaY.

[ii] Ward, Graham P., True Religion, Malden, MA, Blackwell Publishers Ltd., 2003, p.142

[iii] Rule, Sheila, “Khomeini Urges Muslims to Kill Author of Novel.” The New York Times. 14 Feb. 1989. 29 Jan. 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/1989/02/15/world/khomeini-urges-muslims-to-kill-author-of-novel.html.

[iv] “From Threats Against Salman Rushdie To Attacks On ‘Charlie Hebdo’,” NPR. Web. 27 Feb. 2015. http://www.npr.org/blogs/parallels/2015/01/08/375662895/from-threats-against-salman-rushdie-to-attacks-on-charlie-hebdo.

[v] Weisman, Steven R. “Japanese Translator of Rushdie Book Found Slain.” The New York Times, 12 July 1991. Web. 11 Feb. 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/1991/07/13/world/japanese-translator-of-rushdie-book-found-slain.html.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Goodhart, David. “A Tale of Three Cities.” Prospect Magazine. 20 June 2011. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/features/bradford-burnley-oldham-riots-ten-years-on.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] “UK Muslim Demographics.” The Telegraph. 04 Feb. 2011. 30 Jan. 2015. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/wikileaks-files/london-wikileaks/8304838/UK-MUSLIM-DEMOGRAPHICS-C-RE8-02527.html.

[xii] Goodhart, David. “A Tale of Three Cities.” Prospect Magazine. 20 June 2011. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/features/bradford-burnley-oldham-riots-ten-years-on.

[xiii] Bagguley, Paul, and Yasmin Hussein. “The Bradford “Riot” Of 2001: A Preliminary Analysis.” Leeds University. 23 Apr. 2013. Web. 16 Jan. 2014. http://www.leeds.ac.uk/sociology/people/pbdocs/Bradfordriot.doc.

[xiv] Pidd, Helen. “Bradford Synagogue Saved by City’s Muslims.” The Guardian. 20 Dec. 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/20/bradford-synagogue-saved-muslims-jews.

[xv] Rudi’s Story, Chapter 2.” Holocaust Learning. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://holocaustlearning.org/uploads/pdf/Rudi_chapter_2.pdf.

[xvi] Rudi’s Story, Chapter 3.” Holocaust Learning. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://holocaustlearning.org/uploads/pdf/Rudi_chapter_3.pdf.

[xvii] Rudi’s Story, Chapter 6.” Holocaust Learning. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://holocaustlearning.org/uploads/pdf/Rudi_chapter_6.pdf.

[xviii] Pidd, Helen. “Bradford Synagogue Saved by City’s Muslims.” The Guardian. 20 Dec. 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/20/bradford-synagogue-saved-muslims-jews.

[xix] Ditmars, Hadani. “In One Hard-knock British City, a Secret Muslim Donor Helps save a Synagogue.” Haaretz. 21 May 2013. Web. 04 Feb. 2015. http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/jewish-world-features/in-one-hard-knock-british-city-a-secret-muslim-donor-helps-save-a-synagogue.premium-1.525183.

[xx] Pidd, Helen. “Bradford Synagogue Saved by City’s Muslims.” The Guardian. 20 Dec. 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/20/bradford-synagogue-saved-muslims-jews.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] Ditmars, Hadani. “In One Hard-knock British City, a Secret Muslim Donor Helps save a Synagogue.” Haaretz. 21 May 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/jewish-world-features/in-one-hard-knock-british-city-a-secret-muslim-donor-helps-save-a-synagogue.premium-1.525183.

[xxvii] Elgot, Jessica. “Bradford Muslims Rally to Save Synagogue From Closure.” The Huffington Post. 19 Mar. 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2013/03/19/bradford-synagogue-muslims_n_2908254.html

[xxviii] Ditmars, Hadani. “In One Hard-knock British City, a Secret Muslim Donor Helps save a Synagogue.” Haaretz. 21 May 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/jewish-world-features/in-one-hard-knock-british-city-a-secret-muslim-donor-helps-save-a-synagogue.premium-1.525183.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Galloway, George. “Bradford’s Muslim Community and Its Last Remaining Synagogue.” www,parliament.uk. 6 Mar. 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.parliament.uk/edm/2012-13/1149.

[xxxi] Shackle, Samira. “The Mosque’s Aren’t Working in Bradistan.” NewStatesman. 20 Aug. 2010. Web. 20 Jan. 2015. http://www.newstatesman.com/society/2010/08/bradford-british-pakistan.

[xxxii] Pidd, Helen. “Bradford Synagogue Saved by City’s Muslims.” The Guardian. 20 Dec. 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/20/bradford-synagogue-saved-muslims-jews.

[xxxiii] Shackle, Samira. “The Mosque’s Aren’t Working in Bradistan.” NewStatesman. 20 Aug. 2010. Web. 20 Jan. 2015. http://www.newstatesman.com/society/2010/08/bradford-british-pakistan.

[xxxiv] Barnard, Adam. “Children Create Cross-cultural Harmony.” The Guardian. 12 Jan. 2010. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/education/2010/jan/12/cross-cultural-friendships?guni=Article:in body link.

[xxxv] Pidd, Helen. “Bradford Synagogue Saved by City’s Muslims.” The Guardian. 20 Dec. 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/20/bradford-synagogue-saved-muslims-jews.

[xxxvi] Ditmars, Hadani. “In One Hard-knock British City, a Secret Muslim Donor Helps save a Synagogue.” Haaretz. 21 May 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/jewish-world-features/in-one-hard-knock-british-city-a-secret-muslim-donor-helps-save-a-synagogue.premium-1.525183.

[xxxvii] “Cities of Migration.” Cities of Sanctuary, Communities of Welcome. 11 July 2009. Web. 11 Feb. 2015. http://citiesofmigration.ca/good_idea/cities-of-sanctuary-communities-of-welcome/.

[xxxviii] “Bradford City of Sanctuary.” City of Sanctuary. Web. 11 Feb. 2015. http://www.cityofsanctuary.org/bradford.

[xxxix] “Bradford Awarded ‘City of Sanctuary’ Status!” City of Sanctuary, 22 Nov. 2012. Web. 11 Feb. 2015. http://www.cityofsanctuary.org/news/985/bradford-awarded-status.

[xl] Hope Over Hate.” The Economist. 3 Mar. 2011. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.economist.com/node/18289262.

[xli] Ibid.

[xlii] Pidd, Helen. “Bradford Synagogue Saved by City’s Muslims.” The Guardian. 20 Dec. 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/20/bradford-synagogue-saved-muslims-jews.

[xliii] Ditmars, Hadani. “In One Hard-knock British City, a Secret Muslim Donor Helps save a Synagogue.” Haaretz. 21 May 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/jewish-world-features/in-one-hard-knock-british-city-a-secret-muslim-donor-helps-save-a-synagogue.premium-1.525183.

[xliv] Pidd, Helen. “Bradford Synagogue Saved by City’s Muslims.” The Guardian. 20 Dec. 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/20/bradford-synagogue-saved-muslims-jews.

[xlv] Ditmars, Hadani. “In One Hard-knock British City, a Secret Muslim Donor Helps save a Synagogue.” Haaretz. 21 May 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/jewish-world-features/in-one-hard-knock-british-city-a-secret-muslim-donor-helps-save-a-synagogue.premium-1.525183.

[xlvi] Pidd, Helen. “Bradford Synagogue Saved by City’s Muslims.” The Guardian. 20 Dec. 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/20/bradford-synagogue-saved-muslims-jews.

[xlvii] Elgot, Jessica. “Bradford Muslims Rally to Save Synagogue From Closure.” The Huffington Post. 19 Mar. 2013. Web. 17 Jan. 2015. http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2013/03/19/bradford-synagogue-muslims_n_2908254.html.