Vision and Motivation

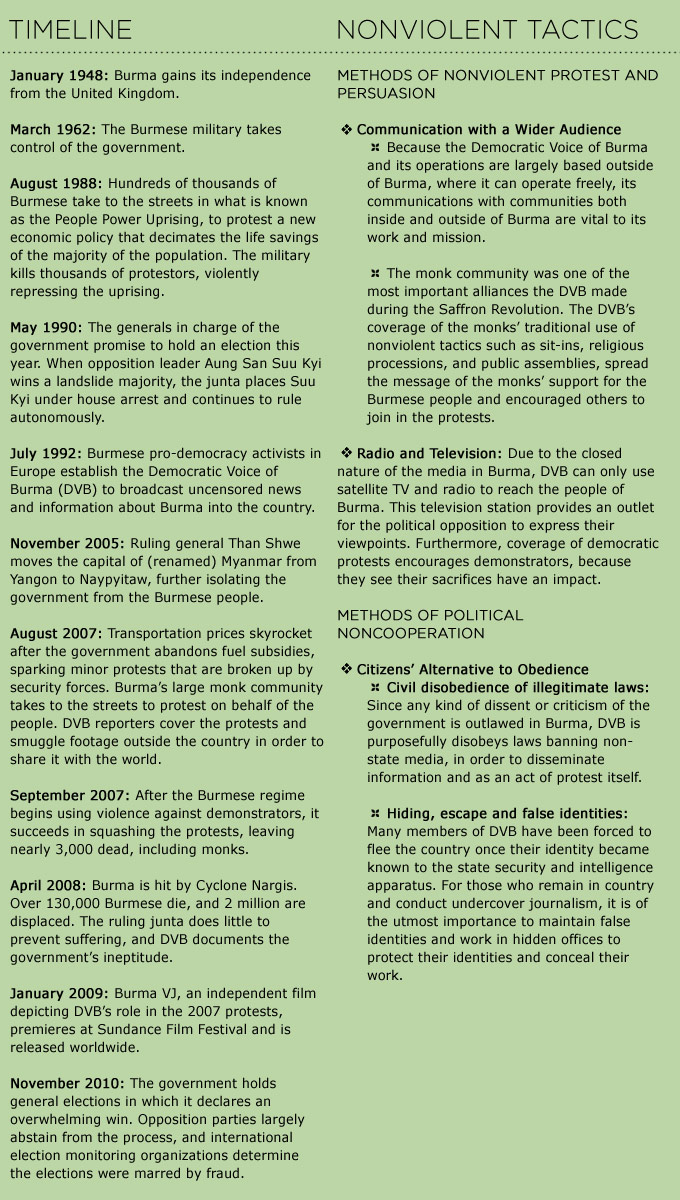

When Burma gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1948, the country was immediately consumed in a power struggle between civilian and military-led governments. By 1962, the military had consolidated its power and was running the country completely. In 1988, the superstitious leader of the country, General Ne Win, ordered all currency notes canceled except the 45 Kyat and 90 Kyat notes, because they were divisible by 9, a lucky number. Led by student protesters, hundreds of thousands of Burmese took to the streets on August 8, 1988 (also known as 8888) when their life savings were decimated by the order. The military quickly stifled the protests with unprecedented use of violence, killing over 3,000 protestors and arresting hundreds more.[1] While generals promised to hold elections in 1990, Aung San Suu Kyi’s overwhelming victory threatened the junta’s power. In response, the junta placed Suu Kyi under house arrest.

When Burma gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1948, the country was immediately consumed in a power struggle between civilian and military-led governments. By 1962, the military had consolidated its power and was running the country completely. In 1988, the superstitious leader of the country, General Ne Win, ordered all currency notes canceled except the 45 Kyat and 90 Kyat notes, because they were divisible by 9, a lucky number. Led by student protesters, hundreds of thousands of Burmese took to the streets on August 8, 1988 (also known as 8888) when their life savings were decimated by the order. The military quickly stifled the protests with unprecedented use of violence, killing over 3,000 protestors and arresting hundreds more.[1] While generals promised to hold elections in 1990, Aung San Suu Kyi’s overwhelming victory threatened the junta’s power. In response, the junta placed Suu Kyi under house arrest.

The 1988 protests revealed a wave of discontent sweeping the Burmese nation; however, the rest of the world remained unaware of the protests and the brutality of the regime. Many of those imprisoned after the protests were surprised by the lack of international and domestic attention to their plight and decided that an independent press was the only way to reach the outside world and to eventually topple the regime.[2] In 1992, Burmese pro-democracy activists in Europe founded an organization called the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB) to provide free press to the Burmese people. Using undercover reporters and satellite and radio streaming into Burma from Oslo, Norway, unbiased news would finally reach the Burmese people, who had until then only had access to state-run television.

In 2007, when transportation prices nearly doubled due to the government’s abandonment of fuel subsidies, thousands of Burmese monks took to the streets to protest on behalf of the people in what became known as the Saffron Revolution, so named for the color of the monks’ robes. Democratic Voice of Burma had the only reporters in the country who could reveal the internal protests to the international community.

Goals and Objectives

When the Democratic Voice of Burma was created in 1992, it established four main goals: “(1) to provide accurate and unbiased news to the people of Burma, (2) to promote understanding and cooperation amongst the various ethnic and religious groups of Burma, (3) to encourage and sustain independent public opinion and enable social and political debate and (4) to impart the ideals of democracy and human rights to the people of Burma.”[3]

When the Democratic Voice of Burma was created in 1992, it established four main goals: “(1) to provide accurate and unbiased news to the people of Burma, (2) to promote understanding and cooperation amongst the various ethnic and religious groups of Burma, (3) to encourage and sustain independent public opinion and enable social and political debate and (4) to impart the ideals of democracy and human rights to the people of Burma.”[3]

Furthermore, DVB acts as a media outlet in exile, providing multiple viewpoints and not simply espousing one political platform. DVB Deputy Executive Director Khin Maung Win describes how “main opposition parties get a forum through which they can express themselves and explain their responses to government policies, which is not possible with the media in the country.”[4]

Leadership

The Democratic Voice of Burma is based in Oslo, Norway, where a full-time staff compiles and broadcasts news programs. 40 reporters inside Burma also shoot live footage of events.[5] Many DVB employees were motivated by their own experiences fighting the regime; for example, the manager of DVB’s network inside Burma explained how he was arrested following the 1988 protests and that “during my time in prison, I expected the outside world to know about the conditions there, but in reality when I got out, I realized the censorship in the country was very serious; even my friends who worked in politics didn’t know exactly what was happening in prison. That’s the most important reason for DVB’s work, and it’s playing a critical role.”[6] Another reporter describes DVB’s mission as follows: “You can’t expect a scoop on CNN. That’s childish. What matters is to keep telling the truth about our country.”[7]

The Democratic Voice of Burma is based in Oslo, Norway, where a full-time staff compiles and broadcasts news programs. 40 reporters inside Burma also shoot live footage of events.[5] Many DVB employees were motivated by their own experiences fighting the regime; for example, the manager of DVB’s network inside Burma explained how he was arrested following the 1988 protests and that “during my time in prison, I expected the outside world to know about the conditions there, but in reality when I got out, I realized the censorship in the country was very serious; even my friends who worked in politics didn’t know exactly what was happening in prison. That’s the most important reason for DVB’s work, and it’s playing a critical role.”[6] Another reporter describes DVB’s mission as follows: “You can’t expect a scoop on CNN. That’s childish. What matters is to keep telling the truth about our country.”[7]

DVB’s undercover reporters are united by their courage and dedication to the cause of democracy in Burma. One reporter explains that “filming inside Burma is a really tough job because there’s so little you can get, and yet at the same time, you’re risking so much, you’re risking your life. And at the same time if you make a mistake…the whole network will be broken, so we’re not just risking our own lives, but those of our other colleagues as well.”[8]

Civic Environment

The violent crackdown on the 1988 student protests ushered in a new era of repression, exemplified by General Than Shwe’s refusal to recognize Aung San Suu Kyi’s victory in the 1990 election. The government further isolated itself from the Burmese people when Than Shwe decided to move the capital in 2005 from Yangon (formerly Rangoon) to the remote town of Naypyitaw.

The violent crackdown on the 1988 student protests ushered in a new era of repression, exemplified by General Than Shwe’s refusal to recognize Aung San Suu Kyi’s victory in the 1990 election. The government further isolated itself from the Burmese people when Than Shwe decided to move the capital in 2005 from Yangon (formerly Rangoon) to the remote town of Naypyitaw.

To repress criticism, the government has outlawed all non-state run media, including opposition and foreign press. Freedom House’s Freedom in the Press report gave Burma a 95/100 score in the “not free” category, describing how “those who publicly express or disseminate views or images that are critical of the regime are subject to harsh punishments, including lengthy prison sentences, as well as assault and intimidation.”[9] During the 2007 protests, the government specifically sought out journalists in the crowds to arrest, prompting one DVB reporter to say that “the military is hunting people with cameras.”[10]

Message and Audience

When the government removed subsidies on fuel in 2007, transportation costs doubled overnight, prompting protests throughout Yangon. However, these acts of civil disobedience were quickly stamped out by police. Meanwhile, the Burmese economy was experiencing a “meltdown” as many Burmese were no longer able to pay the higher costs of public transportation, food, and consumer goods.[11] In response to this suffering, several hundred monks began marching in protest in mid-August. When the Democratic Voice of Burma became aware of this protest, they spoke to a monk leader who revealed that “we gave the generals an ultimatum. If our demands are not met and the generals remain silent, we have prepared for action. We will march all over the country, Mandalay, Rangoon. The whole world must know that the monks are on strike.”[12]

When the government removed subsidies on fuel in 2007, transportation costs doubled overnight, prompting protests throughout Yangon. However, these acts of civil disobedience were quickly stamped out by police. Meanwhile, the Burmese economy was experiencing a “meltdown” as many Burmese were no longer able to pay the higher costs of public transportation, food, and consumer goods.[11] In response to this suffering, several hundred monks began marching in protest in mid-August. When the Democratic Voice of Burma became aware of this protest, they spoke to a monk leader who revealed that “we gave the generals an ultimatum. If our demands are not met and the generals remain silent, we have prepared for action. We will march all over the country, Mandalay, Rangoon. The whole world must know that the monks are on strike.”[12]

Knowing that the monks’ presence would spark wider demonstrations, DVB reporters covered their marches, smuggling the footage to Thailand and Norway so that it could be reported not only to the outside world but also to those inside Burma, in what George Packer calls the media boomerang.[13] DVB Deputy Executive Director Khin Maung Win believes that “activists and the ordinary population are encouraged when their struggle for democracy is covered by the media. This contributes to an increased number of people who express themselves and participate in peaceful demonstrations demanding freedom.”[14]

It was DVB’s use of technology which allowed the marches to grow each day: “The 1988 protests had been far bigger in scale than the 2007 demonstrations, but the world did not see them…The speed and ease of cell phone and email communication facilitated consultation among several of the leading activists. As in 1988, radios were also a crucial source of information, with people listening not only to find out what had happened that day, but what was planned for the next day.”[15]

Despite thousands of protestors and international condemnation, the junta began using force to suppress participation in the protests, intimidating and beating up monks and their supporters. However, thanks in large part to the efforts of DVB and Burmese citizen journalists, the protests “gained a high degree of international news media coverage,” and for a short time, they even became “one of the main topics amongst most international media, despite [Burma’s] usually isolated role.”[16]

Outreach Activities

One of the most important outreach activities the DVB engaged in during the Saffron Revolution was its alliance with the monk community. As the country with the “highest concentration of practicing Buddhists” in the world, Burma is deeply connected to Buddhism: “there is typically a monastery in every village, and the monks are viewed as the community’s spiritual leaders.”[17] Monks provide not only spiritual services but also many social services, including education, food, and shelter. As monks collect alms from the people as payment for food, they were acutely aware of the suffering of the Burmese people following the hike in fuel prices. After members of DVB learned that the monks would be marching for the people, they immediately contacted monks they knew and offered their support.

One of the most important outreach activities the DVB engaged in during the Saffron Revolution was its alliance with the monk community. As the country with the “highest concentration of practicing Buddhists” in the world, Burma is deeply connected to Buddhism: “there is typically a monastery in every village, and the monks are viewed as the community’s spiritual leaders.”[17] Monks provide not only spiritual services but also many social services, including education, food, and shelter. As monks collect alms from the people as payment for food, they were acutely aware of the suffering of the Burmese people following the hike in fuel prices. After members of DVB learned that the monks would be marching for the people, they immediately contacted monks they knew and offered their support.

When the first monks began marching, DVB reporters attended the demonstrations in an attempt to cover them. The monks were initially skeptical that they might be government informants, but according to one reporter, “there were some real intelligence people in the street, and they tried to grab our reporters; the monks protected the reporters and took them into their lines. From [then] on, our guys could walk freely with the monks. We could really work together.”[18] This collaboration was essential to the continuation of DVB’s independent reporting of the Saffron Revolution.

After days of the monks protesting alone, one of the organizers called DVB’s headquarters and asked, “What if we invite the public to join? Would it be fruitful?”[19] Under DVB’s recommendation, the monks began encouraging civilians to begin marching with and creating human chains around the monks’ lines. Many believed that the government would never take action against the monks, who were highly respected and an especially potent challenge to the regime’s authority. While the government allowed the protests to continue for longer than any previous act of civil disobedience, the generals soon began taking violent action against the monks.

Another key to the longevity of the demonstrations was the international community’s role in denouncing the government’s crackdown. International leaders around the world (excluding India and China) and international organizations including the United Nations criticized the Burmese government and urged the junta to take steps toward more democratic rule.[20] Furthermore, DVB gained critical international acclaim when the documentary Burma VJ, depicting DVB’s role in the 2007 protests, was released in 2008. DVB was also one of the top three nominees for the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize.[21]

Despite the Burmese government’s oppression and wanton disregard for its citizens’ wellbeing, DVB has been providing a constant stream of independent media analysis to those inside Burma since its creation in 1992. Recent sham elections[22] demonstrate the junta’s illegitimacy amongst the people and their desire for a free society.

Learn More

News & Analysis

Allchin, Joseph. “DVB ‘Top Three’ for Nobel Peace Prize.” Democratic Voice of Burma. 7 Oct. 2010.

Bannister, Matthew. “Videoing Burma: An Interview with Burma VJ’s ‘Joshua’.” BBC. 11 June 2009.

Democratic Voice of Burma Channel Live (Burmese).

Democratic Voice of Burma Official Website.

MacFarquhar, Neil. “UN Doubts Fairness of Elections in Myanmar.” New York Times. 21 Oct. 2010.

Packer, George. “Drowning: Can the Burmese People Save Themselves?” The New Yorker. 25 Aug. 2008.

Tavaana Exclusive Case Study: Aung San Suu Kyi: Leading the Burmese Democracy Movement.

“Burma/Myanmar: After the Crackdown.” International Crisis Group Asia Report No. 144. 31 Jan. 2008.

“Burma’s 1988 Protests.” BBC News. 25 Sept. 2007.

“Bush Announces More Burma Sanctions.” USA Today. 19 Oct. 2007.

Books

Fink, Christina. Living Silence in Burma: Surviving Under Military Rule. New York: Zed Books, 2009.

Fink, Christina. “The Moment of the Monks: Burma, 2007.” Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-Violent Action from Gandhi to the Present. Ed. Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Multimedia

Ostergaard, Anders. “Burma VJ: Reporting from a Closed Country.” Oscilloscope Laboratories, 2008.

“Burma VJ: Anders Ostergaard and Kin Maung Win Interview.” YouTube. 19 May. 2009.

“Eyes of the Storm.” PBS Wide Lens. 20 August. 2009.

“Myanmar regime trying to suppress protestors.” NBC Nightly News. 27 Sept, 2007.

Footnotes

[1] “Burma’s 1988 Protests.” BBC News. 25 Sept,.2007.

[2] “Eyes of the Storm.” PBS Wide Lens. 20 August 2009.

[3] Democratic Voice of Burma Official Website.

[4] Win, Khin Maung. “Democratic Voice of Burma: Strategies of an Exile Media Organization.” CAMECO’s Media on the Move Part 3 – Potentials of Diaspora Media. Sept. 2008.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Eyes of the Storm.”

[7] Ibid.

[8] Bannister, Matthew. “Videoing Burma: An Interview with Burma VJ’s ‘Joshua’.” BBC. 11 June 2009.

[9] “Freedom in the World: Burma, 2010.” Freedom House. 2010.

[10] Ostergaard, Anders. “Burma VJ: Reporting from a Closed Country.” Oscilloscope Laboratories, 2008.

[11] Jagan, Larry. “Fuel price policy explodes in Myanmar.” Asia Times. 24 Aug. 2007.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Packer, George. “Drowning: Can the Burmese People Save Themselves?” The New Yorker. 25 Aug. 2008.

[14] Win.

[15] Fink, Christina. Living Silence in Burma: Surviving Under Military Rule. New York: Zed Books, 2009. p. 368.

[16] Buck, Lea. “Media and Protests in the Myanmar Crisis.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs. June 2007. PDF.

[17] “Beyond a Spiritual Calling: The Saffron Revolution.” Journal of International Affairs 61, no. 1 (Fall/Winter 2007): 236.

[18] Ostergaard.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “Bush Announces More Burma Sanctions.” USA Today. 19 Oct. 2007.

[21] Allchin, Joseph. “DVB ‘Top Three’ for Nobel Peace Prize.” Democratic Voice of Burma. 7 Oct. 2010.

[22] MacFarquhar, Neil. “UN Doubts Fairness of Elections in Myanmar.” New York Times. 21 Oct. 2010.