Vision and Motivation

On June 12, 2009, the Islamic Republic of Iran held presidential elections that pitted incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad against front-running reformist candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi. In an outcome that was marred by allegations of fraud and outright fabrication, Ahmadinejad was declared the victor with 64% of the popular vote. However, the Mousavi campaign, along with millions of its supporters, believed that they had won.[1] Serious, widespread irregularities in the official results, along with the pervasive belief that they were fraudulent, prompted nationwide protests and the emergence of an opposition “Green Movement” against Ahmadinejad’s re-election. The Iranian government responded with an intense and immediate crackdown, deploying thousands of pro-regime militiamen to attack protestors with lethal force, jailing protestors and prominent reformists, barring foreign journalists from covering the election’s aftermath, and attempting to prevent its citizens from communicating with each other and the outside world. Hundreds if not thousands of Iranians were imprisoned, tortured and raped in the immediate post-election period. Nevertheless, opposition protests continued for months, prompting the regime to amplify repressive measures and place presidential candidates Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi under (still ongoing) house arrest.[2]

On June 12, 2009, the Islamic Republic of Iran held presidential elections that pitted incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad against front-running reformist candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi. In an outcome that was marred by allegations of fraud and outright fabrication, Ahmadinejad was declared the victor with 64% of the popular vote. However, the Mousavi campaign, along with millions of its supporters, believed that they had won.[1] Serious, widespread irregularities in the official results, along with the pervasive belief that they were fraudulent, prompted nationwide protests and the emergence of an opposition “Green Movement” against Ahmadinejad’s re-election. The Iranian government responded with an intense and immediate crackdown, deploying thousands of pro-regime militiamen to attack protestors with lethal force, jailing protestors and prominent reformists, barring foreign journalists from covering the election’s aftermath, and attempting to prevent its citizens from communicating with each other and the outside world. Hundreds if not thousands of Iranians were imprisoned, tortured and raped in the immediate post-election period. Nevertheless, opposition protests continued for months, prompting the regime to amplify repressive measures and place presidential candidates Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi under (still ongoing) house arrest.[2]

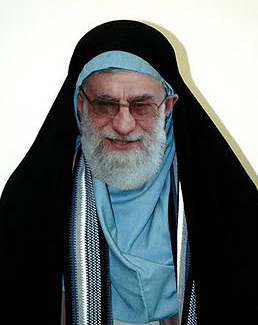

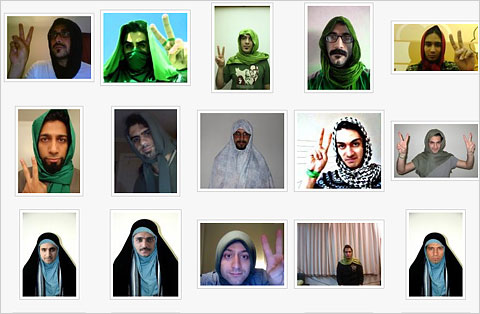

On December 7, 2009, student leader Majid Tavakoli was arrested after criticizing the Iranian regime in an address to a gathering at Tehran’s Amir Kabir University. Tens of thousands of students across the country had held demonstrations in commemoration of Student Day, the anniversary of a fatal student protest in 1953.[3] Although hundreds of activists had been jailed in Iran that year, Tavakoli’s arrest quickly attracted international attention not only because Tavakoli is a prominent student leader but also because regime-affiliated Fars News Agency claimed he had attempted to evade security forces by dressing as a woman. To support the claim, Fars published several photos of the activist wearing a headscarf and chador, the full-body covering worn by religiously conservative Iranian women. Members of the opposition were quick to react to the regime’s attempt to denigrate one of its respected leaders.[4] The regime’s intention may well have been to embarrass the activist, but its photos had the opposite effect. After they were published, hundreds of men, both in Iran and abroad, took part in an online campaign known as “We Are All Majid,” uploading pictures of themselves wearing headscarves like the one the activist was allegedly wearing. The campaign, organized over Facebook and other popular Iranian sites, has been simultaneously described as a show of opposition to the regime, an expression of support for Tavakoli, and a protest against the Islamic Republic’s treatment of women, particularly its violent enforcement of mandatory veiling.

On December 7, 2009, student leader Majid Tavakoli was arrested after criticizing the Iranian regime in an address to a gathering at Tehran’s Amir Kabir University. Tens of thousands of students across the country had held demonstrations in commemoration of Student Day, the anniversary of a fatal student protest in 1953.[3] Although hundreds of activists had been jailed in Iran that year, Tavakoli’s arrest quickly attracted international attention not only because Tavakoli is a prominent student leader but also because regime-affiliated Fars News Agency claimed he had attempted to evade security forces by dressing as a woman. To support the claim, Fars published several photos of the activist wearing a headscarf and chador, the full-body covering worn by religiously conservative Iranian women. Members of the opposition were quick to react to the regime’s attempt to denigrate one of its respected leaders.[4] The regime’s intention may well have been to embarrass the activist, but its photos had the opposite effect. After they were published, hundreds of men, both in Iran and abroad, took part in an online campaign known as “We Are All Majid,” uploading pictures of themselves wearing headscarves like the one the activist was allegedly wearing. The campaign, organized over Facebook and other popular Iranian sites, has been simultaneously described as a show of opposition to the regime, an expression of support for Tavakoli, and a protest against the Islamic Republic’s treatment of women, particularly its violent enforcement of mandatory veiling.

Goals and Objectives

The pro-government news organization’s depiction of the activist was a clear attempt to embarrass a prominent member of the pro-democracy movement, and supporters of the opposition maintained that the story of his attempted escape was a lie. Fars’ report on the arrest referred to Tavakoli as one of the “main leaders of unrest” and directly compared him to former Iranian president Abolhassan Banisadr. Banisadr, who ran afoul of Ayatollah Khomeini soon after becoming revolutionary Iran’s first president, allegedly escaped Iran by shaving his moustache and donning a woman’s headscarf. By linking Tavakoli to Bandisadr, an exiled enemy of the regime, Fars likely sought to bolster its portrayal of him, along with the rest of the opposition, as antirevolutionary pariahs. While the photos were likely intended to stigmatize an outspoken critic of the ruling system, hundreds of Iranians rallied to Tavakoli’s defense through the “We Are All Majid!” campaign, co-opting the women’s clothing they believed he had been forced to wear and transforming them from a symbol of emasculation into one of solidarity and defiance.

The primary goal of the campaign was to protest Majid Tavakoli’s arrest and Fars’ attempt to discredit and humiliate him. The organizers of “We Are All Majid!” aimed to demand and obtain his release, as they made clear on their Facebook page.[5] In the context of Iran’s wider post-election turmoil, “We Are All Majid!” quickly picked up steam and attracted worldwide attention, with hundreds of men uploading pictures of themselves and many flashing “V” signs in support of the Green Movement. The U.S. based site Iranian.com received and uploaded almost 300 pictures of men wearing hijab, many of them green.[6] One well-known picture that emerged from the campaign was one in which the photo was altered to replace Tavakoli’s face with that of Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, reflecting a prevalent belief that the photos published by Fars had been doctored. On Facebook, supporters of the activist created an event called “Free Majid Tavakoli”, using as their banner a painting of a man in a headscarf with the caption “Majid Tavakolis”. The page was the first to ask men to send in pictures of themselves in headscarves as a sign of solidarity with the jailed activist. Over 400 people submitted photographs in the 48 hours after the “Free Majid Tavakoli” Facebook event was created.[7] In addition, its organizers created and directed visitors to an open letter, addressed to head of the Iranian judiciary Ayatollah Amoli Larijani, urging Larijani to release Tavakoli and other jailed student activists.

The primary goal of the campaign was to protest Majid Tavakoli’s arrest and Fars’ attempt to discredit and humiliate him. The organizers of “We Are All Majid!” aimed to demand and obtain his release, as they made clear on their Facebook page.[5] In the context of Iran’s wider post-election turmoil, “We Are All Majid!” quickly picked up steam and attracted worldwide attention, with hundreds of men uploading pictures of themselves and many flashing “V” signs in support of the Green Movement. The U.S. based site Iranian.com received and uploaded almost 300 pictures of men wearing hijab, many of them green.[6] One well-known picture that emerged from the campaign was one in which the photo was altered to replace Tavakoli’s face with that of Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, reflecting a prevalent belief that the photos published by Fars had been doctored. On Facebook, supporters of the activist created an event called “Free Majid Tavakoli”, using as their banner a painting of a man in a headscarf with the caption “Majid Tavakolis”. The page was the first to ask men to send in pictures of themselves in headscarves as a sign of solidarity with the jailed activist. Over 400 people submitted photographs in the 48 hours after the “Free Majid Tavakoli” Facebook event was created.[7] In addition, its organizers created and directed visitors to an open letter, addressed to head of the Iranian judiciary Ayatollah Amoli Larijani, urging Larijani to release Tavakoli and other jailed student activists.

Leadership

Although Tavakoli himself was in prison, his previous record of activism in Iran and his profile within the student movement helped give impetus to the online campaign organized on his behalf. Prior to the events of June 2009, Tavakoli and several other students from Amir Kabir University had been arrested in May 2007, for publishing anti-government articles and caricatures in four student publications. Although they denied the charges and claimed that their logos had been stolen to produce counterfeit issues, Tavakoli and two other student publishers were arrested and charged with producing anti-state propaganda and insulting the Supreme Leader. According to letters written by the students while in detention, they were tortured in prison and forced to make false confessions. After initially being convicted and sentenced to 3.5 years in prison, Tavakoli was released in August of 2008. He was arrested again in February of 2009, however, being released again only weeks before the presidential elections.[8]

Although Tavakoli himself was in prison, his previous record of activism in Iran and his profile within the student movement helped give impetus to the online campaign organized on his behalf. Prior to the events of June 2009, Tavakoli and several other students from Amir Kabir University had been arrested in May 2007, for publishing anti-government articles and caricatures in four student publications. Although they denied the charges and claimed that their logos had been stolen to produce counterfeit issues, Tavakoli and two other student publishers were arrested and charged with producing anti-state propaganda and insulting the Supreme Leader. According to letters written by the students while in detention, they were tortured in prison and forced to make false confessions. After initially being convicted and sentenced to 3.5 years in prison, Tavakoli was released in August of 2008. He was arrested again in February of 2009, however, being released again only weeks before the presidential elections.[8]

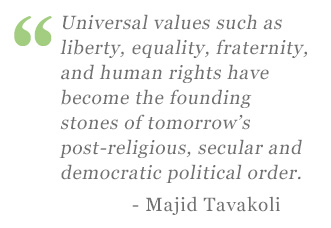

In the context of Iran’s post-election unrest, Tavakoli’s last arrest was the result of a speech he gave at Amir Kabir on December 7, 2009, in which he criticized the Iranian government’s foreign policy, its failed economic policies, its treatment of women and ethnic minorities, and its repressive measures against civil society organizations. In letters written from prison (translated to English by Tavaana), Tavakoli has since spelled out his vision for the Green Movement and the future of the Iranian opposition. In June of 2010, Tavakoli urged other young people to continue fighting for change, writing from behind bars that “today’s generation should be fully aware of the precious opportunity it has been offered in present-day Iran, an opportunity so eagerly awaited by people in all parts of the world: a chance for them to actively participate in the making of their own destiny.” At the same time, he stressed the importance of the movement’s commitment to non-violence and its inclusion of a wide range of opposition forces, saying that both will help the Green Movement to succeed. In his letter, Tavakoli defined the movement and identified its core values: “The universality of our values, encompassing all the essential aspirations stemming from contemporary movements, the respect for others’ values and rights, and the antidespotic character of our revolutionary movement, has become a founding value. This is complemented by pluralism and tolerance as guarantors of tomorrow’s peaceful sociopolitical coexistence. Universal values such as liberty, equality, fraternity, and human rights have become the founding stones of tomorrow’s post-religious, secular and democratic political order… One must know that the Green Movement of the people of Iran is a wide-ranging popular one, formed in order to change the status quo in a nonviolent campaign known as a velvet or “color” revolution for liberty and democracy, in a continuation of similar movements [elsewhere]. Regardless of what the regime, its propaganda machine and followers say, the velvet revolutionary character of the [Green] movement is a matter of pride for us all…”[9]

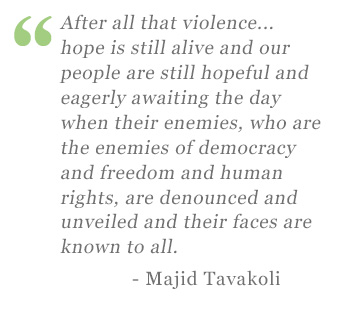

Tavakoli’s speech at Amir Kabir earned him harsh punishment from the Iranian judiciary. After a trial from which his lawyer was barred, Tavakoli was again convicted of anti-system propaganda and insulting government officials. This time, however, he was sentenced to 8.5 years in prison, and from January to May 2010, he was mostly held in solitary confinement. In protest of his mistreatment, Tavakoli went on a hunger strike in late May and began to develop serious respiratory issues.[10] Following his confinement in Evin Prison, he was transferred to Raja’i-Shahr, a facility which primarily houses violent criminals.[11] In spite of these hardships, the young activist made it clear that he believes the regime’s repression will ultimately fail, writing in September 2010 that “After all that violence, all that betrayal, all that mediocrity; after all those forced confessions and all those show trials, false interviews, tortures, solitary confinements, rapes, summary justice and executions; after all the slandering and cynicism, hope is still alive and our people are still hopeful and eagerly awaiting the day when their enemies, who are the enemies of democracy and freedom and human rights, are denounced and unveiled and their faces are known to all.”[12]

Tavakoli’s speech at Amir Kabir earned him harsh punishment from the Iranian judiciary. After a trial from which his lawyer was barred, Tavakoli was again convicted of anti-system propaganda and insulting government officials. This time, however, he was sentenced to 8.5 years in prison, and from January to May 2010, he was mostly held in solitary confinement. In protest of his mistreatment, Tavakoli went on a hunger strike in late May and began to develop serious respiratory issues.[10] Following his confinement in Evin Prison, he was transferred to Raja’i-Shahr, a facility which primarily houses violent criminals.[11] In spite of these hardships, the young activist made it clear that he believes the regime’s repression will ultimately fail, writing in September 2010 that “After all that violence, all that betrayal, all that mediocrity; after all those forced confessions and all those show trials, false interviews, tortures, solitary confinements, rapes, summary justice and executions; after all the slandering and cynicism, hope is still alive and our people are still hopeful and eagerly awaiting the day when their enemies, who are the enemies of democracy and freedom and human rights, are denounced and unveiled and their faces are known to all.”[12]

Civic Environment

Iran’s theocracy is headed by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who has held the post since 1989 and who, despite a seemingly sophisticated state apparatus of institutions, exercises ultimate control over the government and affairs of state. Among the tools used by Khamenei to maintain his control is the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), a paramilitary force dedicated to the preservation of the regime and the Supreme Leader. In addition to its military responsibilities, the IRGC oversees the Basij, a pro-regime militia which is responsible for breaking up demonstrations and suppressing internal dissent.

Under the Islamic Republic, Iran has never had a free press or civil society. Even when reformist President Mohammad Khatami was in office and reformists controlled Parliament, hardliners went to great lengths to stymie efforts to expand civil liberties. In 1998, several Iranian dissidents were murdered in a chain of orchestrated assassinations by elements of the Intelligence Ministry, and security forces used lethal force to put down student demonstrations in 1999.[13] In addition, the judiciary closed over 100 reformist newspapers from 2001-2004, and hundreds of journalists, students, and activists were jailed.[14]

In the aftermath of the June 2009 elections, the Basij militias were almost immediately deployed to crush demonstrations in Tehran and other parts of the country. Security forces used live ammunition to fire on demonstrators, as evidenced by the videotaped death of Neda Agha-Soltan on June 20. Because of their active role in the reform movement, students such as Tavakoli faced some of the harshest reprisals. In one of the crisis’ most well-known incidents, members of the Basij attacked the dormitories of Tehran University on the night of June 14, killing at least five students. [15] According to opposition sources, 72 people in all were killed in the months after the election.[16] One hallmark of this wave of repression was the jailing of top revolutionaries and prominent regime officials. Along with reformist journalists and activists, these former regime insiders were the subject of televised, Stalinesque sham trials that chilled the nation.

Within just a week of the election, Iranian authorities had arrested 500 members of the opposition, journalists, and students, including well-known Iranian political figures. The detainees included Saeed Hajarian, a former advisor to Mohammad Khatami who was imprisoned despite needing constant medical care, former Vice President Mohammad-Ali Abtahi, former parliamentarians Behzad Nabavi and Mostafa Tajzadeh, and 78-year-old Ebrahim Yazdi, who had been a leading revolutionary and Minister of Foreign Affairs.[17] Iranian journalists became a primary target of the crackdown, with over 100 being arrested and 50 forced to leave the country.[18] In 2009, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) ranked Iran 172nd in press freedom, or fourth-worst out of the 175 countries included in the group’s report. Among the dangers faced by journalists in the aftermath of the election, RSF cited “automatic prior censorship, state surveillance of journalists, mistreatment, journalists forced to flee the country, illegal arrests and imprisonment.”[19] In order to prevent news of the unrest from spreading, the Iranian government cut off cell phone service, blocked social networking sites, and sharply curtailed the activities of foreign media, forcing international news outlets to rely on amateur footage shot by protestors and uploaded to YouTube and other sites. As the protest movement continued, Iranian authorities throttled Internet connectivity and disrupted text messaging services, in addition to blocking websites, such as Gmail, most often used by activists to communicate.[20]

Within just a week of the election, Iranian authorities had arrested 500 members of the opposition, journalists, and students, including well-known Iranian political figures. The detainees included Saeed Hajarian, a former advisor to Mohammad Khatami who was imprisoned despite needing constant medical care, former Vice President Mohammad-Ali Abtahi, former parliamentarians Behzad Nabavi and Mostafa Tajzadeh, and 78-year-old Ebrahim Yazdi, who had been a leading revolutionary and Minister of Foreign Affairs.[17] Iranian journalists became a primary target of the crackdown, with over 100 being arrested and 50 forced to leave the country.[18] In 2009, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) ranked Iran 172nd in press freedom, or fourth-worst out of the 175 countries included in the group’s report. Among the dangers faced by journalists in the aftermath of the election, RSF cited “automatic prior censorship, state surveillance of journalists, mistreatment, journalists forced to flee the country, illegal arrests and imprisonment.”[19] In order to prevent news of the unrest from spreading, the Iranian government cut off cell phone service, blocked social networking sites, and sharply curtailed the activities of foreign media, forcing international news outlets to rely on amateur footage shot by protestors and uploaded to YouTube and other sites. As the protest movement continued, Iranian authorities throttled Internet connectivity and disrupted text messaging services, in addition to blocking websites, such as Gmail, most often used by activists to communicate.[20]

Although the government managed to quell the uprising, sharp restrictions on online communications and civic activism remain, leading reformists to boycott the spring 2012 legislative elections and leaving Iran’s hardliners in uncontested control of the state apparatus.[21] A glaring sign of the threat perceived by the regime from the election and its aftermath is the continued house arrest of presidential candidates Mir Hossein Mousavi, who was Prime Minister during the Iran-Iraq War, and Mehdi Karroubi, a two-time Speaker of Parliament.

Message and Audience

“We Are All Majid!” had a clear message to the Iranian government: despite its attempt to humiliate a prominent member of the opposition by emasculating him, many other men were willing to stand in solidarity with Tavakoli and show that “there is no shame in being a woman”, to quote the official Facebook event.[22] The Islamic Association of Amir Kabir University, where Tavakoli gave his speech before being arrested, emphatically delivered a similar response to the photos. The group expressed its support for both Tavakoli and other prisoners by stating: “Not only Majid Tavakoli, but all of the students held captive by oppression, are the pride of the student movement, whether in men’s or in women’s clothing.”[23] As the success of the Facebook event made clear, many others supported this stance. In addition, 1,453 people signed the open letter asking the Iranian judiciary to free him.[24]

“We Are All Majid!” had a clear message to the Iranian government: despite its attempt to humiliate a prominent member of the opposition by emasculating him, many other men were willing to stand in solidarity with Tavakoli and show that “there is no shame in being a woman”, to quote the official Facebook event.[22] The Islamic Association of Amir Kabir University, where Tavakoli gave his speech before being arrested, emphatically delivered a similar response to the photos. The group expressed its support for both Tavakoli and other prisoners by stating: “Not only Majid Tavakoli, but all of the students held captive by oppression, are the pride of the student movement, whether in men’s or in women’s clothing.”[23] As the success of the Facebook event made clear, many others supported this stance. In addition, 1,453 people signed the open letter asking the Iranian judiciary to free him.[24]

In addition to supporting Tavakoli, some participants and observers of the “We Are All Majid!” campaign interpreted Iranian men proudly wearing headscarves to be a protest against the discrimination faced by Iranian women, most visible in the form of mandatory hijab. In praising “We Are All Majid!”, Nobel Prize winner Shirin Ebadi told its participants: “You shouted that you respect your mothers and defend the human rights of your sisters.”[25]

Outreach Activities

The unorthodox nature of the campaign and the attention that was already being focused on the Green Movement meant that “We Are All Majid!” received considerable coverage among both Iranians and the international press. In the days after his arrest, major international news outlets such as the New York Times, the BBC, CNN, the Guardian, and Le Monde reported on Tavakoli’s detention and the online movement he had inspired in print, on-air, and online. Furthermore, many of those pleading Tavakoli’s case and participating in the campaign were Iranians living abroad. One popular YouTube video from France featured a group of Iranian men in Paris, wearing hejab as seen in the photographs of Tavakoli in Fars News’ report.[26] In addition, the website Iranian.com, which called for readers to submit their own photographs, is based in the United States and usually serves the Iranian diaspora.[27] Thanks to Facebook and YouTube, Iranian and non-Iranian supporters of Tavakoli inside and outside Iran were able to communicate and coordinate a unified response to his arrest, along with a clear message of defiance to the Iranian government.

The unorthodox nature of the campaign and the attention that was already being focused on the Green Movement meant that “We Are All Majid!” received considerable coverage among both Iranians and the international press. In the days after his arrest, major international news outlets such as the New York Times, the BBC, CNN, the Guardian, and Le Monde reported on Tavakoli’s detention and the online movement he had inspired in print, on-air, and online. Furthermore, many of those pleading Tavakoli’s case and participating in the campaign were Iranians living abroad. One popular YouTube video from France featured a group of Iranian men in Paris, wearing hejab as seen in the photographs of Tavakoli in Fars News’ report.[26] In addition, the website Iranian.com, which called for readers to submit their own photographs, is based in the United States and usually serves the Iranian diaspora.[27] Thanks to Facebook and YouTube, Iranian and non-Iranian supporters of Tavakoli inside and outside Iran were able to communicate and coordinate a unified response to his arrest, along with a clear message of defiance to the Iranian government.

As a social media campaign, “We Are All Majid!” succeeded in publicizing Tavakoli’s arrest and rebuking the government’s attempt to ostracize the young activist. Despite the worldwide outcry and months of protests, however, Majid Tavakoli remains in prison and the Green Movement has, for the time being, been silenced. As Iranian hardliners have marginalized calls for reform and even Mahmoud Ahmadinejad now faces opposition from former allies in the conservative-dominated Parliament and the Supreme Leader’s office, the hope for real political change that swept Iran in 2009 is, for the time being, dormant. As Majid himself wrote from his prison cell, however, the road to democracy is an often long and difficult one, particularly in Iran’s case. As he told his fellow students from Raja’i-Shahr prison: “More than a hundred years of struggle against despotic regimes has finally taught us, in the drought of knowledge and humanity of the Islamic Republic, resistance and the ability to remain vibrant, alive and creative, in order to put an end to this long, sad story of sterility. The hundred year-long stories has taught us that liberty has a price to be paid, risks to be taken.”[28]

Learn More

News & Analysis

Amnesty International Page for Majid Tavakoli.

“Free Majid Tavakoli” Facebook event.

Tavakoli, Majid. “For Change.” Tavaana translation.

Tavakoli, Majid. “Let’s Remain on the Side of the People.” Tavaana translation.

Tavakoli, Majid. “Student Day Speech, Dec. 7, 2008” (in Persian with English translation).

Books

Hashemi, Nader and Danny Postel (Eds.). The People Reloaded: The Green Movement and the Struggle for Iran’s Future. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House. 2010.

Multimedia

Link Compilation of “men in hijab” photographs (YouTube).

Footnotes

[1] Worth, Robert F. and Nazila Fathi. “Both Sides Claim Victory in Presidential Election in Iran.” The New York Times. 12 June 2009.

[2] “Iran police fire tear gas at opposition rally in Tehran.” BBC News. 14 Feb. 2011.

[3] Mackey, Robert. “Dec. 7: Updates on Student Protests in Iran.” New York Times: The Lede blog. 7 Dec. 2009.

[4] Tait, Robert. “Iran regime depicts male student in chador as shaming tactic.” The Guardian. 11 Dec. 2009.

[5] “Free Majid Tavakoli” Facebook event.

[6] Iranian.com Gallery.

[7] “Free Majid Tavakoli” Facebook event.

[8] International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. “Majid Tavakoli.” 19 March 2009.

[9] Tavakoli, Majid. “For Change.” Tavaana translation.

[10] Esfandiari, Golnaz. “Health Concerns Surround Majid Tavakoli, Heart of Iran’s Student Movement.” RFE/RL. 26 May 2010.

[11] Amnesty International. “Student Activist Jailed for Speaking Out.”

[12] Tavakoli, Majid. “Let’s Remain on the Side of the People.” Tavaana translation.

[13] “Iran student protests: Five years on.” BBC News. 9 July 2004.

[14] “Freedom in the World: Iran, Freedom House, 2004.”

[15] Lyons, John. “Students slaughtered in Tehran University attack.” The Australian. 19 June 2009.

[16] “Iran opposition says 72 killed in vote protests.” AFP, 3 Sept. 2009.

[17] Tait, Robert. “Iran arrests 500 activists in wake of election protests.” The Guardian. 17 June 2009.

[18] “World Report: Iran.” Reporters Without Borders.

[19] “Press Freedom Index 2009.” Reporters Without Borders.

[20] Fassihi, Farnaz. “Iran Mobilizes to Stifle Opposition Protests.” The Wall Street Journal. 10 Feb. 2010.

[21] Gladstone, Rick. “Election Fears and Economic Woes Pose New Challenges for Iran’s Leaders.” The New York Times. 2 Jan. 2012.

[22] “Free Majid Tavakoli” Facebook event.

[23] “Iran Postelection Protests for Student Activist.” Radio Farda, 11 Dec. 2009.

[24] “Free Majid Tavakoli” Facebook event.

[25] “Iran’s Nobel Peace Laureate Praises ‘Men in Hijabs’ Campaign.” RFE/RL, 16 Dec. 2009.

[26] “We are all Majid Tavakoli!” YouTube. 13 Dec. 2009.

[27] “About Us”, Iranian.com.

[28] Tavakoli, Majid. “Let’s Remain on the Side of the People.” Tavaana translation.